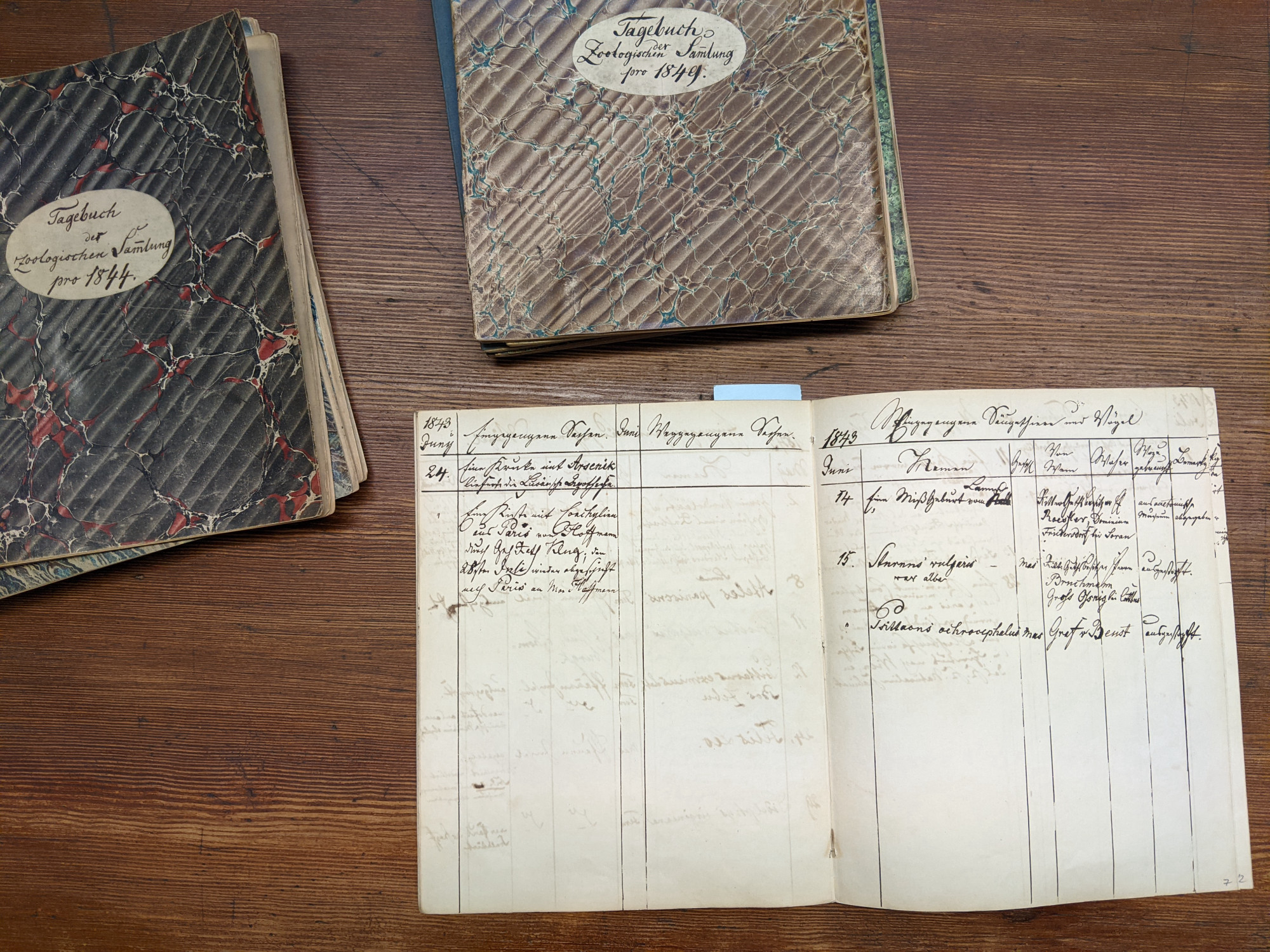

Item records in the logbooks of the preparators of the Zoological Museum, which was part of the Natural History Museum in Berlin. (Image: Sarina Schirmer/HBSB/MfN. All rights reserved.)

The open logbook is one of thirteen preserved item registers in the Zoological Collection that were kept between 1843 and 1858. It is an example of a whole series of record-keeping media that have been used since the founding of the Zoological Museum in 1810 to record and manage its  holdings. Back then, different

holdings. Back then, different  formats and forms of record-keeping,

formats and forms of record-keeping,  labels,

labels,  specimen lists,

specimen lists,  inventories and logbooks, existed alongside each other. Not even Wilhelm Peters, who became director of the Zoological Museum in 1857, was able to carry out his plans for a consistent cataloguing system. As one of the three sub-collections that were merged under the roof of one museum building in 1888, the research-focused collection of the Zoological Museum, also referred to as the Zoological Collection, has formed the historical corpus of the collection belonging to what is now the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin. It should not be confused with the

inventories and logbooks, existed alongside each other. Not even Wilhelm Peters, who became director of the Zoological Museum in 1857, was able to carry out his plans for a consistent cataloguing system. As one of the three sub-collections that were merged under the roof of one museum building in 1888, the research-focused collection of the Zoological Museum, also referred to as the Zoological Collection, has formed the historical corpus of the collection belonging to what is now the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin. It should not be confused with the  Zoological Teaching Collection, which was established in 1884 as the university teaching collection of the newly founded Zoological Institute of the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, today’s Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Zoological Teaching Collection, which was established in 1884 as the university teaching collection of the newly founded Zoological Institute of the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, today’s Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Friedrich Beyer, who in his role as second assistant prepared animals in the museum from 1817 until his death in 1851, created this logbook, in which he documented the arrivals and departures of the  animals that were sent to the museum to be prepared as

animals that were sent to the museum to be prepared as  specimens, including, e.g., boxes of bird skins and stuffed birds, and ‘little boxes’ filled with mollusc shells or snails. Moreover, some mammals and birds are listed separately with information about the context in which they were acquired and how they were prepared. The categories ‘From whom’, ‘Whence’, and ‘What for’ also contain detailed information about the

specimens, including, e.g., boxes of bird skins and stuffed birds, and ‘little boxes’ filled with mollusc shells or snails. Moreover, some mammals and birds are listed separately with information about the context in which they were acquired and how they were prepared. The categories ‘From whom’, ‘Whence’, and ‘What for’ also contain detailed information about the  animal’s provenance, how it had been processed, and how it was being used in the museum collection or

animal’s provenance, how it had been processed, and how it was being used in the museum collection or  exhibition. It is not quite clear whether, how, or by whom these notes were used in the museum, but they were probably made as records of the work performed by preparators. Similar records of day-to-day business are still being kept in the preparation workshops of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin. For historians and cultural studies scholars, Friedrich Beyer’s logbooks are exciting historical documents that can be used to better understand the unique histories of objects like the

exhibition. It is not quite clear whether, how, or by whom these notes were used in the museum, but they were probably made as records of the work performed by preparators. Similar records of day-to-day business are still being kept in the preparation workshops of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin. For historians and cultural studies scholars, Friedrich Beyer’s logbooks are exciting historical documents that can be used to better understand the unique histories of objects like the  lion-tiger as well as the

lion-tiger as well as the  trajectories of animals between different institutions. On the other hand, they are testament to a certain form of record-keeping for collection items that was created for a specific practical purpose, which in this case reveals what preparation work at the museum was like back then.

trajectories of animals between different institutions. On the other hand, they are testament to a certain form of record-keeping for collection items that was created for a specific practical purpose, which in this case reveals what preparation work at the museum was like back then.