Mulberry tree at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, 2021. (Image: Britta Lange)

While the great dinosaur skeleton in the main hall of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin is known throughout the city and the world, nobody seems to know anything about the giant tree in the museum’s courtyard. In the passage that runs between the museum, today’s Institute of Biophysics, and the Thaer Institute of Agricultural and Horticultural Sciences at the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, there is a large mulberry tree. What is its story? The clues lead back to 18th-century Prussia, to museum collections and villages in Brandenburg, to naturalists, kings, and silkworms.

Morus alba at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin and in the Villages of Brandenburg

The collection manager of the Lepidoptera (butterfly and moth) collection, Viola Richter, points the tree out to me as she looks for  display cases filled with silkworm specimens at my request in autumn 2020.1 One of these cases displays the four zoological stages in the development of Bombyx mori, the silk moth, each represented by a number of specimens: the egg, the caterpillar (bombyx), the pupa in its cocoon, and the hatched moth.

display cases filled with silkworm specimens at my request in autumn 2020.1 One of these cases displays the four zoological stages in the development of Bombyx mori, the silk moth, each represented by a number of specimens: the egg, the caterpillar (bombyx), the pupa in its cocoon, and the hatched moth.

Old display case showing the developmental stages of Bombyx mori, Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, Lepidoptera Collection, 2020. (Image: Britta Lange/MfN. All rights reserved.)

The Bombyx mori, which has been cultivated in Asia and Europe for thousands of years, feeds exclusively on the leaves of the white mulberry tree, Morus alba. Morus is also the Latin term for blackberry (in French ‘mûre’ is blackberry and ‘mûrier’ mulberry tree), which indicates the form and colour of the tree’s fruit. Because the silkworm has coevolved with the mulberry tree, fresh green leaves from the Morus alba must be available to provide the insects with sustenance and thus to support the production of silk threads. The German term for silkworm, ‘Maulbeerspinner’, literally translates as ‘mulberry caterpillar’, revealing the close interconnection between the silkworm and the mulberry tree. In nature, the mulberry tree is as inseparable from the animal as it is in its German designation.

Today, nobody in Berlin breeds silkworms anymore, not at the museum, the university, in factories, or in private homes. However, the white mulberry tree remains and decorates the street in the courtyard. Its height – perhaps 15 meters – suggests that it is already many decades old. Ferdinand Damaschun, previously a mineralogist at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, informs me that the tree was already very tall when he began working at the museum in 1974. The head of the museum at the time, the botanist Walter Vent, who was able to see the tree from his director’s office, asked him about it.2 It is likely that the tree did not actually belong to the museum building, which was completed in 1889, but to the building of the former  Agricultural University (Landwirtschaftliche Hochschule) opposite, which was finished in 1880. This institution was at least indirectly linked to the history of the silkworm in Brandenburg.

Agricultural University (Landwirtschaftliche Hochschule) opposite, which was finished in 1880. This institution was at least indirectly linked to the history of the silkworm in Brandenburg.

Lectures began here in the winter semester of 1880/81, and on 14 February 1881, the institute received the title of Royal Agricultural University of Berlin (Königliche Landwirtschaftliche Hochschule Berlin).3 This meant that, in Berlin, which had become the capital of the empire ten years earlier, a field of research had been institutionalised that the renowned doctor and agriculturalist Albrecht Daniel Thaer (1752-1828) from Celle had already established in rural Brandenburg. Thaer, who is considered the founder of agricultural studies, opened the Agricultural Teaching Institute in 1806 at the Rittergut Möglin estate in Brandenburg, where he experimented with crop rotation and the breeding of merino sheep. The institute, which was called the Royal Prussian Academic Teaching Facility for Agriculture (Königliche Preußische Akademische Lehranstalt des Landbaus) from 1819, was a direct predecessor to the academic agricultural training provided in Berlin. Moreover, from 1810 to 1819, Thaer gave agricultural lectures as an associate professor at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Berlin, which had been founded in 1810, and published numerous papers on agricultural economics and ‘agronomy’ (agricultural studies), as well as  animal breeding, based on the research he carried out in Möglin.

animal breeding, based on the research he carried out in Möglin.

Even if it cannot yet been proven that Thaer had mulberry trees cultivated in Möglin, he researched and taught at the heart of a landscape where, above all under the direction of the Prussian King Frederick II (1712-1786), numerous people were breeding silkworms in the 18th century and thus also planting and cultivating white mulberry trees. Documents like the chronicles of the surrounding Brandenburg villages reveal that it was not just large enterprises like the silk weavers’ colony in Wriezen,4 located just a few kilometres away, that were being launched; rather, smaller groups of mulberry trees and bushes were also being planted in orchards, cemeteries, and boulevards.5

The ‘ladies of Friedland’ – Helene Charlotte von Lestwitz (1754-1803) and her daughter Henriette Charlotte von Itzenplitz (1772-1848) – who received in their salons in Kunersdorf Thaer and other personalities from Berlin’s scholarly and artistic circles, like the brothers Alexander and Wilhelm Humboldt, ran orchards and orangeries filled with exotic plants, including white and black mulberry.6 The wine master Schmidt had already obtained 30 mulberry trees from Friedland in 1754, which he used to set up an orchard around the church in Bollersdorf, located a few kilometres away.7 In 1763, in turn, the sacristan at the cemetery in Heckelberg planted an orchard,8 and, in 1788, the teacher and sacristan of the village of Prädikow set up a mulberry orchard at the cemetery.9 Many more examples would follow.

Knowledge about Bombyx mori

We have to take a range of different perspectives to trace the history of this animal, which has disappeared from Brandenburg and Berlin. In contrast to so called  pests like

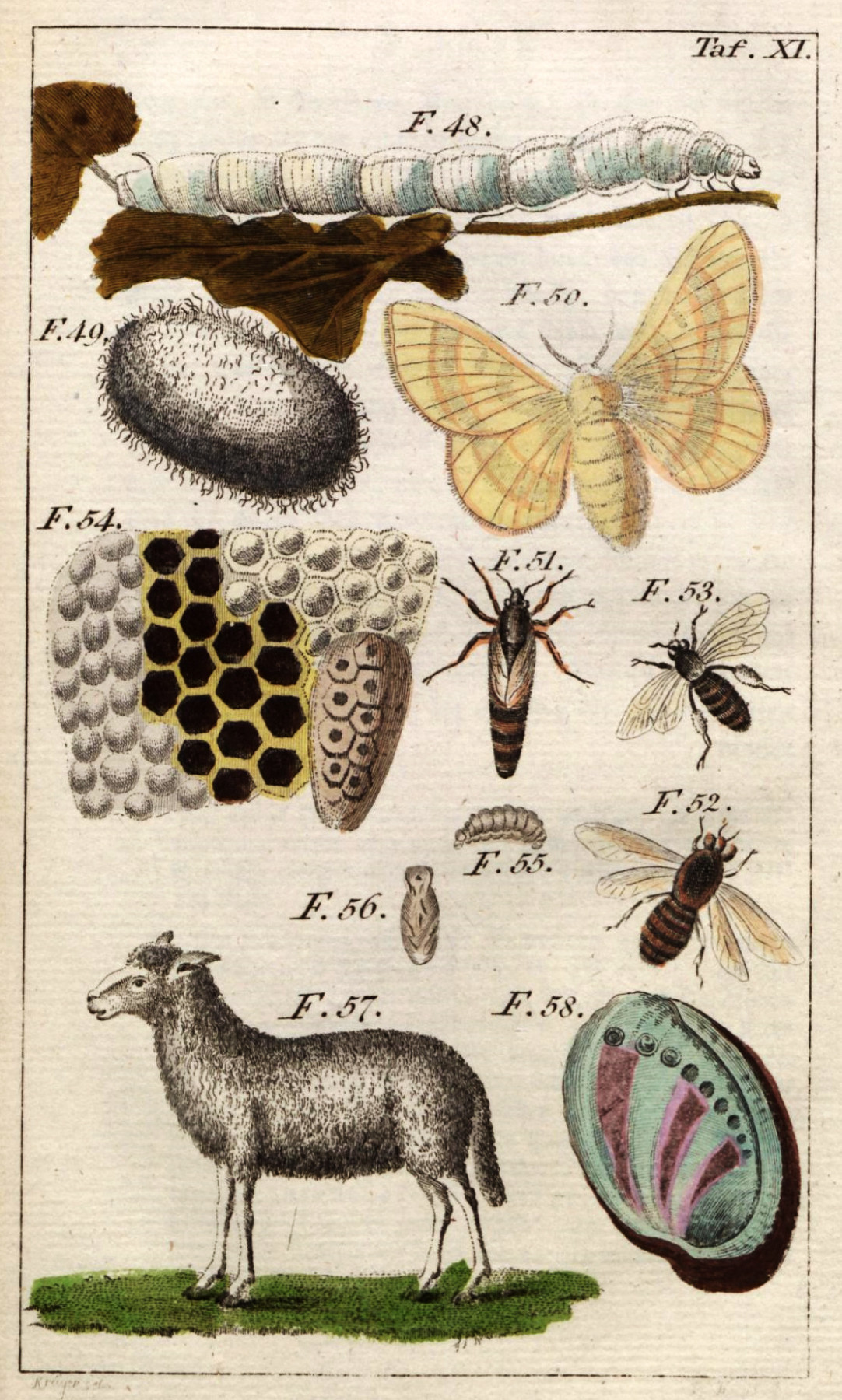

pests like  rats, silkworms were seen as ‘working animals’ and were cultivated exclusively for the purpose of manufacturing a single product: silk thread. In natural philosophy, where insects had been considered ‘inferior’ animals from the age of Aristotle up into the early modern period, silkworms stuck out, namely as the only ‘beneficial insects’ of this class beside honey bees. This explains why silkworms and honey bees were often depicted together in the popular science publications of the 18th century.

rats, silkworms were seen as ‘working animals’ and were cultivated exclusively for the purpose of manufacturing a single product: silk thread. In natural philosophy, where insects had been considered ‘inferior’ animals from the age of Aristotle up into the early modern period, silkworms stuck out, namely as the only ‘beneficial insects’ of this class beside honey bees. This explains why silkworms and honey bees were often depicted together in the popular science publications of the 18th century.

Silkworms and honeybees appear together in this popular-scientific depiction of insects from 1794.10

Unlike the bee and other working animals from the classes of birds, fish, and mammals, however, Bombyx mori could not be found in the wild in Prussia. It was only in human captivity and in spaces that were artificially heated that the eggs could survive the winter. This lack of silkworms in the wild is one reason that, with the disappearance of silk farming, the living silkworm has been completely forgotten, at least outside of specialist research – as they did not naturally occur in the wild due to the climatic conditions of northern Europe. Those who want to reconstruct the  history of silk farming in Prussian Brandenburg by focusing on these animals are thus confronted with the problem that they and the memory of them are no longer present. Their disappearance from everyday life means that it is no longer possible to draw on live sources to study these animals on a daily basis. In order to understand the practices of silkworm cultivation and breeding, and the techniques used to obtain silk, researchers must rely, firstly, on visual and written sources and, secondly, on the remains of material culture. These include not just the products of silk farming (clothing, accessories, furnishings, wallpaper), but also collection items such as display cases,

history of silk farming in Prussian Brandenburg by focusing on these animals are thus confronted with the problem that they and the memory of them are no longer present. Their disappearance from everyday life means that it is no longer possible to draw on live sources to study these animals on a daily basis. In order to understand the practices of silkworm cultivation and breeding, and the techniques used to obtain silk, researchers must rely, firstly, on visual and written sources and, secondly, on the remains of material culture. These include not just the products of silk farming (clothing, accessories, furnishings, wallpaper), but also collection items such as display cases,  models, and specimens, as well as the instruments and buildings of silk farming that remain. Clues have also been left behind as traces in the landscape – orchard buildings and old mulberry trees.

models, and specimens, as well as the instruments and buildings of silk farming that remain. Clues have also been left behind as traces in the landscape – orchard buildings and old mulberry trees.

What do we know today about the silkworm? What did people back then know about this animal, and where did their knowledge come from? Both the production of knowledge at the time and cultural narratives about silkworms derive, as I would like to argue, from everyday interactions with the animals and observations that were made of them.11 Practices of cultivation; sensory experiences like touching, smelling, and listening to the animals; and economies of breeding and killing wove together with moments of observation and reflection. ‘Coexisting’ with silkworms led to two significant outcomes. Firstly, new scientific knowledge about the animals took shape and was  recorded, and, secondly, empirical and everyday knowledge led to aesthetic reflections and provided food for thought: the properties of the silkworm, above all its pupation and the hatching of the moth from its cocoon, i.e., its complete, visible metamorphosis/shapeshifting, were translated into models of thought in other societal contexts – in religion, art, economics, and politics. The animal also became a model or object of thought.

recorded, and, secondly, empirical and everyday knowledge led to aesthetic reflections and provided food for thought: the properties of the silkworm, above all its pupation and the hatching of the moth from its cocoon, i.e., its complete, visible metamorphosis/shapeshifting, were translated into models of thought in other societal contexts – in religion, art, economics, and politics. The animal also became a model or object of thought.

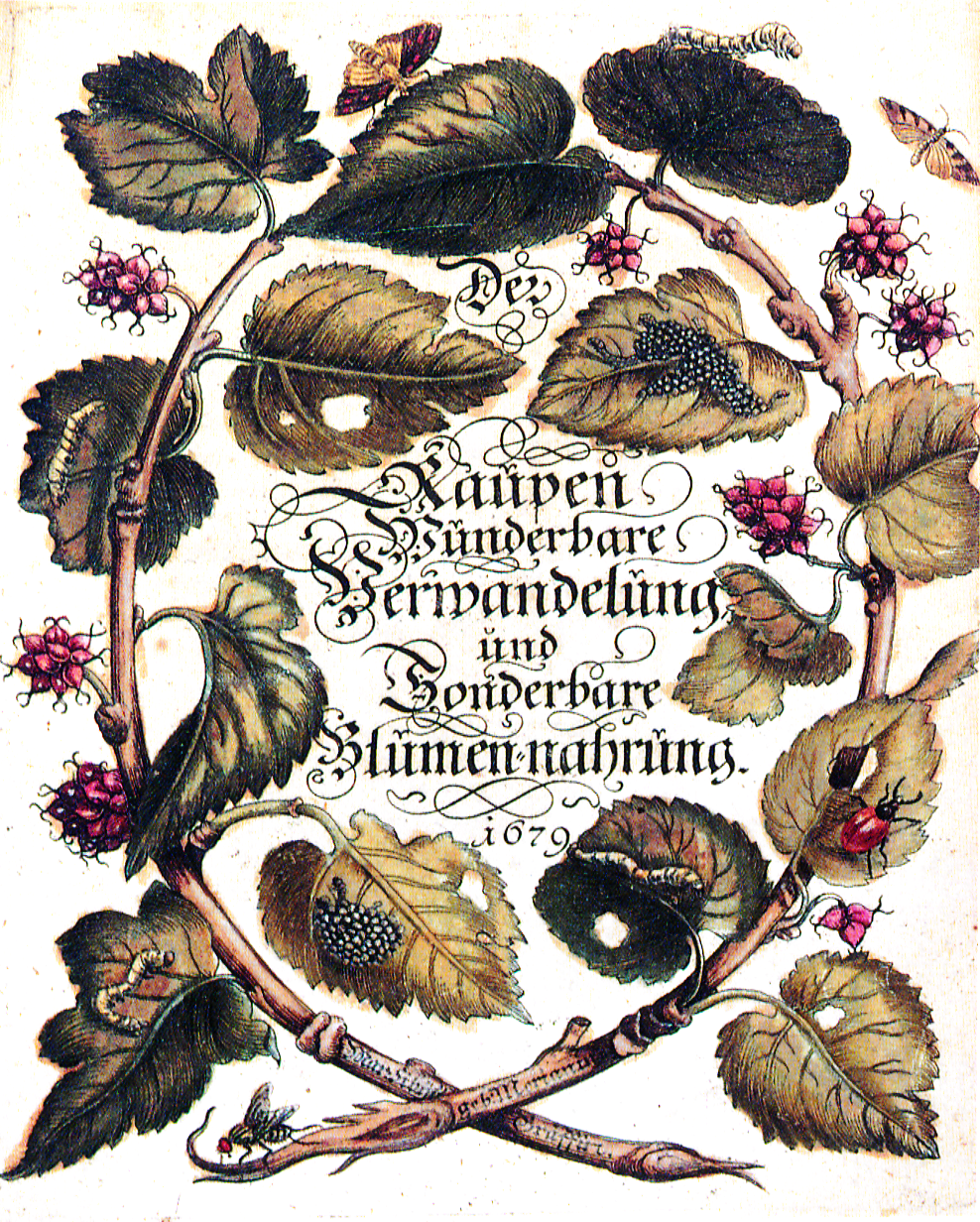

In Europe, most silkworm breeders must have known that the caterpillars hatch from eggs that are laid beforehand by moths, because it was this experience that enabled them to breed silkworms in the first place. But it was the artist and scholar Maria Sibylla von Merian who, in her 1679 book The Wondrous Transformation and Flower Diet of the Caterpillars (Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandelung und sonderbare Blumen-nahrung), based on her own observations of caterpillars (and indeed not just of silkworms), was the first to formulate a rebuttal of the Aristotelian theory of spontaneous generation, according to which inferior animals like worms and blowflies were not produced through sexual procreation but emerged from refuse and fumes.12 By refuting the idea of spontaneous generation, Maria Sibylla von Merian laid the foundations for entomology and modern zoology,13 which, on the one hand, were increasingly taking leave of mythological and theological narratives and, on the other, were gaining new insights and developing new terminology.

In the 18th century, the zoologist  Carl Linnaeus coined the term metamorphosis to describe the shapeshifting of some animal species14 – and the transformation from an egg to a caterpillar, from a pupa in a cocoon to a moth is now considered a complete metamorphosis. Because Bombyx mori takes just a few weeks to complete this process, during which the animal passes through all four stages (egg, caterpillar, pupa, moth), this species is particularly well suited to illustrating zoological metamorphosis, which is why it was still possible to view live silkworms at Berlin Zoo’s insectarium in the 2010s.

Carl Linnaeus coined the term metamorphosis to describe the shapeshifting of some animal species14 – and the transformation from an egg to a caterpillar, from a pupa in a cocoon to a moth is now considered a complete metamorphosis. Because Bombyx mori takes just a few weeks to complete this process, during which the animal passes through all four stages (egg, caterpillar, pupa, moth), this species is particularly well suited to illustrating zoological metamorphosis, which is why it was still possible to view live silkworms at Berlin Zoo’s insectarium in the 2010s.

The book cover for Maria Sibylla von Merian’s The Wondrous Transformation and Flower Diet of the Caterpillars shows the interplay between caterpillars and plants. (Nuremberg/Frankfurt: Bey Johann Andreas Graffen, 1679.)

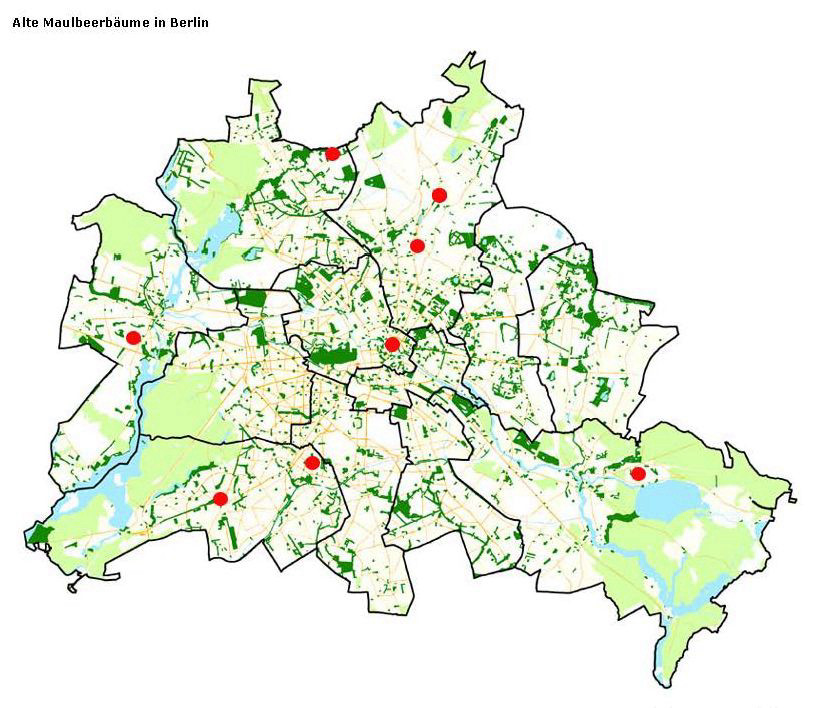

Old Mulberry Trees in Berlin

In 1854, after  silk culture had gone through its boom in 17th- and 18th-century Prussia and had established itself as an industry, pébrine, a disease that affects silkworms, crossed over from France into Germany. Most silkworm populations were wiped out,15 and it was no longer possible to revive the industry in the long term. Because silk was now only being cultivated by amateurs, its history in Prussia was opened up to historicisation and analysis. By the end of the 19th century, the animals that had formed the backbone of silk farming had disappeared, but some of the trees remained. People kept using their fruit to make jellies, desserts, and syrup, and their bright green leaves and golden crowns in autumn ensured that they stayed in use as decorative trees. Even though the orchards were cut down (as they had been after the death of Frederick the Great as well), a number of trees outlived their agricultural utilisation. For example, there are still very old mulberry trees scattered about in Köpenick and at the cemetery in Zehlendorf – both of which were located outside the city gates at the time the trees were planted.16 The map of old mulberry trees issued by the Berlin Senate Department clearly shows how the urban area has expanded since the 18th century, and how the ‘country’ has grown into the city that was still largely shaped by agriculture and livestock farming in the 19th century.17

silk culture had gone through its boom in 17th- and 18th-century Prussia and had established itself as an industry, pébrine, a disease that affects silkworms, crossed over from France into Germany. Most silkworm populations were wiped out,15 and it was no longer possible to revive the industry in the long term. Because silk was now only being cultivated by amateurs, its history in Prussia was opened up to historicisation and analysis. By the end of the 19th century, the animals that had formed the backbone of silk farming had disappeared, but some of the trees remained. People kept using their fruit to make jellies, desserts, and syrup, and their bright green leaves and golden crowns in autumn ensured that they stayed in use as decorative trees. Even though the orchards were cut down (as they had been after the death of Frederick the Great as well), a number of trees outlived their agricultural utilisation. For example, there are still very old mulberry trees scattered about in Köpenick and at the cemetery in Zehlendorf – both of which were located outside the city gates at the time the trees were planted.16 The map of old mulberry trees issued by the Berlin Senate Department clearly shows how the urban area has expanded since the 18th century, and how the ‘country’ has grown into the city that was still largely shaped by agriculture and livestock farming in the 19th century.17

The red dots mark old mulberry trees in Berlin.18 (Source: Senate of Berlin)

Perhaps the most spectacular of these trees is the old mulberry tree that still stands in a rear courtyard at the intersection of Friedrichstraße and Claire-Waldoff-Straße on the premises of today’s Charité hospital.

Old mulberry tree in Berlin-Mitte near the Charité campus, 2020. (Image: Britta Lange)

It was planted and maintained in connection with a settlement of French Huguenots that established itself there in 1685. Today, the old tree looks like a crooked pollard willow and stands at the edge of a park area, where it is propped up by a steel construction that has traffic and water notices attached to it. It looks like nature has grown into culture – or vice versa. Although the signs mark acts of human administration and logistics, there is no sign pointing to the tree as a natural monument or as a cultural memorial to the Huguenot settlement and the forgotten industry of silk culture. Even though the tree was probably already around when the Edict of Nantes was revoked in 1685, which led to the religious refugees’ emigration from France to Prussia and the Prussian king giving them permission to cultivate silk in Berlin, it is considered (if it is considered at all) something that is part of ‘nature’ – but not even that, because in the tree register of the city of Berlin it is nowhere to be found.19 Today, the French Cemetery lies a little further north on Chausseestraße, and it is here that we find a small row of replanted mulberry trees with a little plaque pointing out their connection to silkworm breeding. In cemeteries and parks in particular, we see young trees being replanted where the oldest mulberry trees have disappeared, although their connection to the silkworm has been forgotten. A landscape gardening tradition has thus developed that has taken leave of its industrial roots and only very seldom actively reminds us of them.

Mulberry trees at the French Cemetery in Berlin-Mitte, 2020. (Image: Britta Lange)

Completely unbeknownst to the city administration and the tree register, in contrast, is the white mulberry tree on Invalidenstraße, which might have been planted at the Agricultural University for teaching purposes. It might have had a connection to the procurement of the model of a  papier mâché silkworm from the workshop of the Parisian modeller Louis Auzoux.20 It stands to reason that the actual tree and the caterpillar model were acquired at the same time, and that silkworms were possibly kept as well to observe and to teach students about the insect’s diet, upkeep, and reproduction. We cannot know for sure, because although the tree still bears witness, it cannot tell us its whole story.

papier mâché silkworm from the workshop of the Parisian modeller Louis Auzoux.20 It stands to reason that the actual tree and the caterpillar model were acquired at the same time, and that silkworms were possibly kept as well to observe and to teach students about the insect’s diet, upkeep, and reproduction. We cannot know for sure, because although the tree still bears witness, it cannot tell us its whole story.

- My thanks go to Viola Richter, Sandra Miehlbradt, and Ferdinand Damaschun (all Museum für Naturalkunde Berlin), Gerhard Scholtz (Zoological Teaching Collection of the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin), Sabine Graefe (Thaer Museum Möglin), and Wolfgang Bokelmann (formerly of the Thaer-Institut of the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin) for providing me with information, as well as to Sofie Fingado and Estela Braun Carrasco for their help researching.↩

- Personal email, 05.05.2021.↩

- “Albrecht Daniel Thaer-Institut für Agrar- und Gartenbauwissenschaften”. Humboldt-Uniceristät zu Berlin, no date. https://www.agrar.hu-berlin.de/de/institut/profil/geschichte/standardseite (24.08.2021); see also Volker Klemm. Von der Königlichen Akademie des Landbaus in Möglin zur Landwirtschaftlich-Gärtnerischen Fakultät der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Berlin: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, 1998.↩

- The silk farming building erected in 1781 now houses a Sparkasse bank branch.↩

- Copies of the chronicles are preserved today at the Thaer memorial in Möglin.↩

- The Reichenower trees of 1754 came from the “Friedland orchard”. On Kunersdorf and Friedland, see Friedrich Walter. Verzeichniss der auf den Friedländischen Gütern cultivirten Gewächse: Nebst einem Beitrag zur Flora der Mittelmark; Alphabetisch geordnet so weit sie bestimmt sind. 3rd ed. 1815: 35.↩

- Rudolf Schmidt. Die Herrschaft Friedland: Nachrichten zur Geschichte von Alt- und Neufriedland, Gottesgabe, Carlsdorf, Kleinbarnim, Grube, Sietzing, Gersdorf, Batzlow, Ringenwalde, Burgwall, Metzdorf, Horst, Wubrigsberg. Kreisausschuss des Kreises Oberbarnim (ed.). Bad Freienwalde/Oder, 1928: 206.↩

- Rudolf Schmidt. 6 Höhendörfer im Kreise Oberbarnim: Zur Heimatgeschichte von Trampe, Klobbicke, Tuchen, Heckelberg, Freudenberg, Beiersdorf. Kreisausschuss des Kreises Oberbarnim (ed.). Bad Freienwalde/Oder, 1926: 137.↩

- Rudolf Schmidt. Die Herrschaft Eckardstein: I. Beiträge zur Entwicklungsgeschichte von Prötzel, Prädikow, Grunow, Reichenow, Sternebeck, Harnecop, Bliesdorf und Vevais. Kreisausschuss des Kreises Oberbarnim (ed.). Bad Freienwalde/Oder, 1926: 68.↩

- Neue Bilder Gallerie für junge Söhne und Töchter zur angenehmen und nützlichen Selbstbeschäftigung aus dem Reiche der Natur, Kunst, Sitten, und des gemeinen Lebens. Berlin: Oehmigcke, 1794: plate XI.↩

- Although women played a major role in this cultivation and observation, they were rarely mentioned in the writings published on silk culture and were only listed as authors in exceptional cases.↩

- Maria Sibylla Merian. Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandelung und sonderbare Blumen-nahrung. Nuremberg/Frankfurt: Bey Johann Andreas Graffen, 1679.↩

- Cf. Ulrich Kutschera. “Pionierin der Entwicklungsbiologie und Ökologie: Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)”. Biologie unserer Zeit 1, no. 47 (2017): 28-36. https://doi.org/10.1002/biuz.201710610.↩

- Cf. Georg Töpfer. “Metamorphose”. In Historisches Wörterbuch der Biologie: Geschichte und Theorie der Biologischen Grundbegriffe, vol. 3. Stuttgart: Metzler, 2011: 573-591.↩

- Cf. Junko Thérèse Takeda. “Global Insects: Silkworms, Sericulture, and Statecraft in Napoleonic France and Tokugawa Japan”.French History 28, no. 2 (2014): 207-225. https://doi.org/10.1093/fh/cru044.↩

- Cf. Berlin Senate Department for the Environment, Transport, and Climate Protection. “Maulbeerbäume in Berlin”. Berlin.de, no date. https://www.berlin.de/senuvk/umwelt/stadtgruen/stadtbaeume/de/maulbeeren/index.shtml (28.07.2021).↩

- See for example Clemens Wischermann. “Der Ort des Tieres in der Stadt”. Informationen zur modernen Stadtgeschichte 2 (2009): 5-12.↩

- Berlin Senate Department for the Environment, Transport and Climate Protection. “Standorte alter Maulbeerbäume”. Berlin.de, no date. https://www.berlin.de/senuvk/umwelt/stadtgruen/stadtbaeume/de/maulbeeren/fenster_karte.shtml (20.8.2021).↩

- Berlin Senate Department for Urban Development and Housing. Berlin.de, no date. https://www.stadtentwicklung.berlin.de/geoinformation/fis-broker/ (24.08.2021).↩

- The collapsible functional model is now part of the Zoological Teaching Collection at the Humboldt-University zu Berlin; cf. “Modell, Raupe, Seidenspinner”. Humboldt-Universität database entry, no date. https://www.sammlungen.hu-berlin.de/objekte/zoologische-lehrsammlung/8322/ (24.08.2021).↩