Gateway to Berlin Zoo known as the Elephant Gate (Elefantentor), around 1938. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

How could the zoo – a nearly 100-year-old educational and recreational institution that displayed live animals for the purposes of education and entertainment – serve the aims of National Socialism? As will become evident, from 1933 onward, Berlin Zoo became a stage for colonialism and a site of racist exclusion, as well as an instrument of National Socialist propaganda.

After Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor of the German Reich on 30 January 1933, the new regime did everything in its power to permeate all areas of social life. To this end, it sought to exercise control over labor law, but especially to dominate in the spheres of culture and propaganda. Its agenda encompassed Berlin’s most popular educational and recreational institution, the Zoological Garden and its aquarium. The zoo was quick to accommodate National Socialist policy and its local representatives, Gauleiter of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) Joseph Goebbels and National Socialist Prussian Prime Minister Hermann Göring. This was mainly down to the zoo’s management and supervisory board. Nazi policies affected every aspect of the zoo’s operation. The management and the public became involved in antisemitic policies; the German war of aggression and extermination allowed animals to be obtained from new sources; it affected exhibition practices and the selection of the animals to be displayed, and it altered how work was organised at the zoo. The widespread exploitation of forced laborers also became an everyday practice.

The Heck Family

In 1932, Lutz Heck became director of the Berlin Zoological Garden. He succeeded his father, Ludwig Heck, who had previously held the position since 1888. Politically, the Heck family were German nationalists and colonial revisionists, and they maintained close contact with actors from the right-wing conservative nationalist milieu. Lutz and Ludwig Heck expressed clear enthusiasm for National Socialist politics in the books they published in 1935 and 1938. Both paid homage in their works to the “Führer”, who had “fully consciously […] based the state on the ideology of blood and soil”.1 As early as June 1933, Lutz Heck became a sponsoring member of the Schutzstaffel (SS),2 and supported the SS party organisation of the NSDAP with regular donations. In return, like all sponsors, he received lapel pins that made his loyalty to the regime apparent to all.

Lutz Heck soon also became personally acquainted with Hermann Göring, Prussian Prime Minister and Reich Minister of Aviation, and from 1934 also head of the Reich’s forestry ministry (Reichsforstmeister) and chief huntsman of the Reich (Reichsjägermeister).

In January 1934, Göring presented his plans for the Schorfheide to a group of forestry officials. He wanted to establish a large nature reserve, where he also wished to hunt the largest land mammal in Europe the European bison.3 In order to make Göring’s plans a reality, Lutz Heck decided to increase the zoo’s population of wisents, or European bison, as quickly as possible. He aimed to do this by means of ‘upgrading’ – breeding with the wisent’s closest relative, the North American bison.4 In 1935, he undertook an expedition to Canada “on behalf of the Reichsforstmeister and Reichsjägermeister Hermann Göring, the German hunting community, and the zoo.”5 The trip’s purpose was, among other things, to procure bison to support his breeding efforts – for a closer look at the genealogy of breeding programmes, see  Zoos and Conservation.

Zoos and Conservation.

Lutz Heck supported the regime in whatever way he could. His books and publications praised the Nazi state’s laws on game conservation.6 At Heck’s instigation, Göring was appointed leader of the Fachschaft Deutsche Bracken Olpe, a club for breeders of hunting dogs7 – certainly a minor honor, but ideal for winning over Göring, who was an enthusiastic hunter. Lutz Heck also provided Göring with  lion cubs to keep as pets, which Heck took back when the animals had grown out of the ‘petting age’.8

lion cubs to keep as pets, which Heck took back when the animals had grown out of the ‘petting age’.8

The Supervisory Board

From 1933 onward, the zoo also put the NSDAP’s antisemitic and racist policies into practice. The Supervisory Board subjected two of its long-standing members, Georg Siegmann and Walter Simon, to humiliating discussions about their Jewish identity.9 They resigned from their positions in the same year as a result of the pressure exerted on them.10

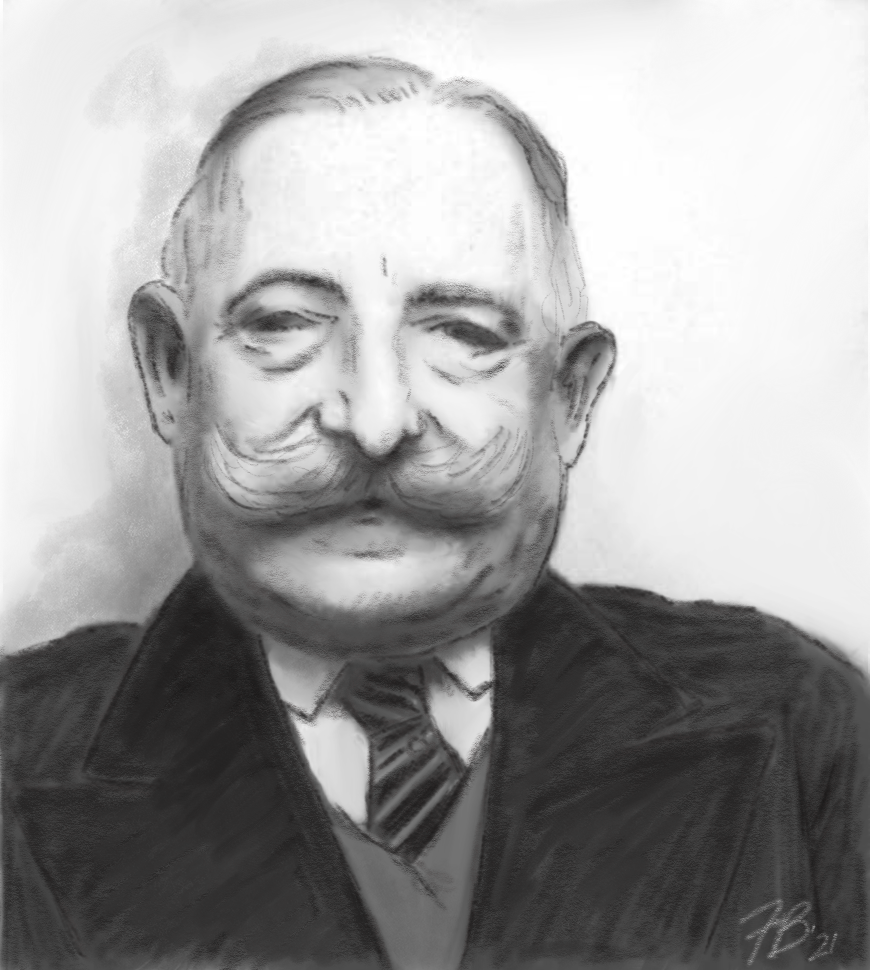

Georg Siegmann was expelled from the Supervisory Board and murdered by the National Socialists. (Drawing: Filippo Bertoni)

During this period, vacancies on the Supervisory Board were immediately filled by National Socialist candidates, such as the last governor of the German colony of Togo, Adolf Friedrich of Mecklenburg, SS Brigadeführer Ewald von Massow, and the racist anthropologist and pioneer of National Socialist racial theories Eugen Fischer.11 Georg Siegmann and his wife Helene were deported to the concentration camp at Theresienstadt and from here taken to Auschwitz, where they were murdered. Walter Simon and his wife were deported to Riga, where they were both murdered.

The Supervisory Board of the Zoological Garden Berlin AG on a visit to the zoo. Lutz Heck (third from the left), Eugen Fischer (fourth from the left), and Oskar Heinroth (first from the right). (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

As with many of Berlin’s large companies, the zoo’s workforce was also ‘Nazified’ within a few weeks. Workers’ councils were replaced by appointed representatives and the staff band played against a backdrop featuring a portrait of Hitler, a swastika, and the symbol of the German Labour Front, the National Socialist organisation that was to replace the free trade unions.

The zoo band with  “Bobby” the gorilla’s face displayed on the band’s drum kit, 1938. (AZGB, image: Springer. All rights reserved.)

“Bobby” the gorilla’s face displayed on the band’s drum kit, 1938. (AZGB, image: Springer. All rights reserved.)

The Zoo and Propaganda

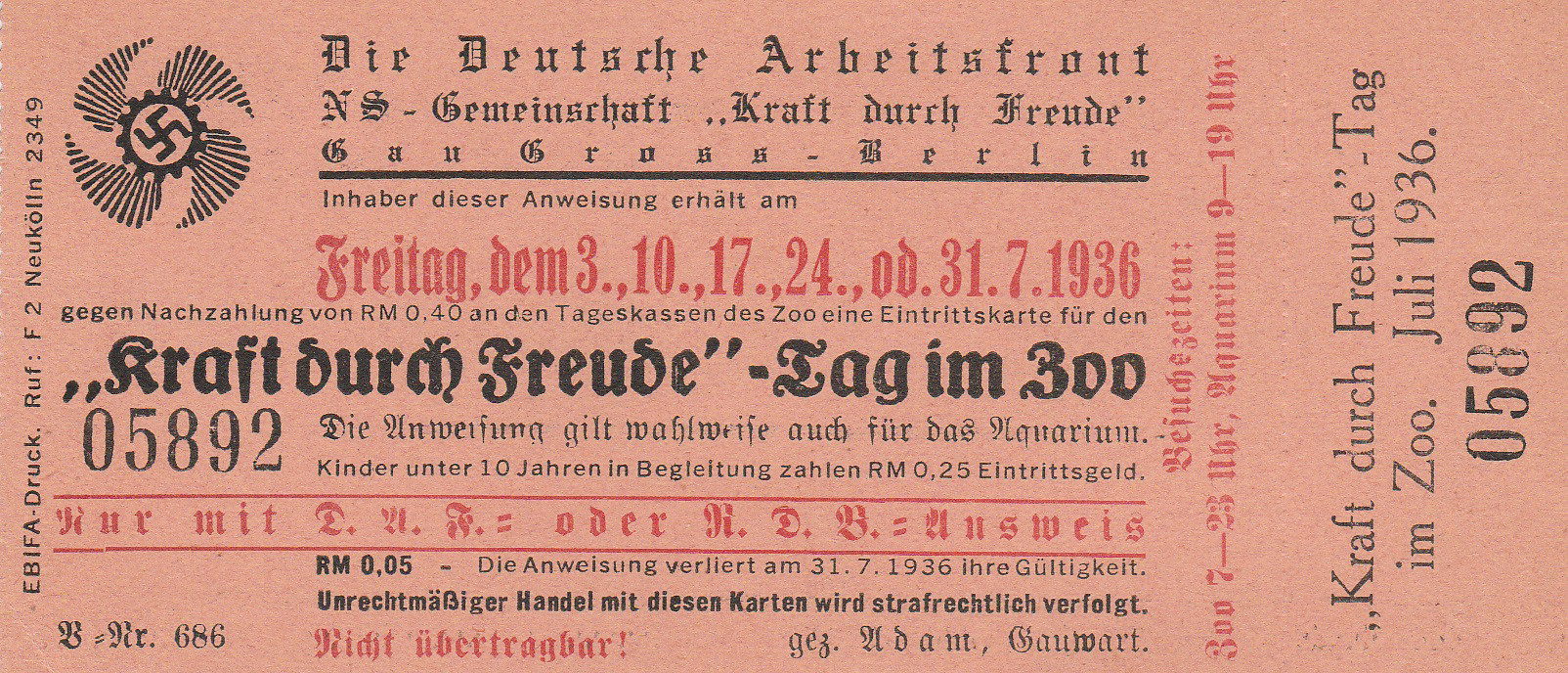

Financially, the zoo flourished with the rise of National Socialism, quite the  opposite of the post-war period. This was facilitated by the fact that it catered to National Socialist visitors and the nationalist ideology of the ruling party. From May 1933 onward, there were substantial reductions in the price of admission for members of National Socialist organisations, such as the NSDAP, the National Socialist Motorist Corps, the Sturmabteilung (SA), the Schutzstaffel (SS), and the German nationalist military Der Stahlhelm.12 The following year, the zoo management went on to lower ticket prices for all visitors, “in accordance with the aims of the National Socialist state leadership”.13 In 1935, it recorded a surge of visitors, in all likelihood partly thanks to an agreement between the zoo and the Nazi recreational organisation ‘Kraft durch Freude’.

opposite of the post-war period. This was facilitated by the fact that it catered to National Socialist visitors and the nationalist ideology of the ruling party. From May 1933 onward, there were substantial reductions in the price of admission for members of National Socialist organisations, such as the NSDAP, the National Socialist Motorist Corps, the Sturmabteilung (SA), the Schutzstaffel (SS), and the German nationalist military Der Stahlhelm.12 The following year, the zoo management went on to lower ticket prices for all visitors, “in accordance with the aims of the National Socialist state leadership”.13 In 1935, it recorded a surge of visitors, in all likelihood partly thanks to an agreement between the zoo and the Nazi recreational organisation ‘Kraft durch Freude’.

Entry ticket for ‘Kraft durch Freude’ Day at the zoo, 1936. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

Lutz Heck for his part used the political climate to serve his own  colonial revisionist ambitions. In 1933, he sponsored a ‘Colonial Art Exhibition’ in the zoo’s exhibition halls, where he displayed a replica of the encampments built for his animal trapping expeditions in Eastern Africa.14 In 1927/28, the animals he captured included giraffes from the former colony of German East Africa,15 the territory of Tanganyika subsequently ruled by the British. In the summer of 1934, the zoo commemorated Colonial Remembrance Day by hosting a ‘Kolonialer Volkstag’ or ‘Colonial Day of the People’. A press tour took reporters to see ‘German Colonial Animals’ – meaning animals from former German colonies. In 1937, the zoo celebrated a ‘Colonial Festival’ under a slogan ‘Everyone should visit Africa once’.16

colonial revisionist ambitions. In 1933, he sponsored a ‘Colonial Art Exhibition’ in the zoo’s exhibition halls, where he displayed a replica of the encampments built for his animal trapping expeditions in Eastern Africa.14 In 1927/28, the animals he captured included giraffes from the former colony of German East Africa,15 the territory of Tanganyika subsequently ruled by the British. In the summer of 1934, the zoo commemorated Colonial Remembrance Day by hosting a ‘Kolonialer Volkstag’ or ‘Colonial Day of the People’. A press tour took reporters to see ‘German Colonial Animals’ – meaning animals from former German colonies. In 1937, the zoo celebrated a ‘Colonial Festival’ under a slogan ‘Everyone should visit Africa once’.16

In 1936, in time for the Summer Olympics in Berlin, the zoo opened a 2,000-square-meter lion steppe. 1936 also brought the many additional tourists who had travelled to Berlin for the Games, thanks to whom the zoo enjoyed a record attendance of more than two million paying guests that year.17 Berlin Zoo participated in the elaborate propaganda orchestrated for the Games, and provided animals for the Olympic Village, which housed the athletes’ living quarters, supplying native waterfowl and fallow deer to frolic around a central pond.

At the behest of Prussian Prime Minister Hermann Göring, the zoo was finally granted an extension to its grounds on the edge of the Tiergarten park in August 1935. The police and the Reiter-SA (Sturmabteilung) had initially objected, as the extension would have narrowed a bridle path, but Göring’s wishes were ultimately fulfilled.18 Heck used the new strip of land for large enclosures housing ‘native animal species’. ‘German predators’, such as wolves and bears, were displayed alongside ‘German birds of prey’, such as eagles and buzzards. For propaganda purposes, it was of no relevance that all of these animals were also to be found in neighbouring countries of the German Reich, and that some, like the bear, no longer even existed in Germany. Their framing as ‘German animals’ worked to legitimise the National Socialists’ policy of expansion.19  Native livestock were displayed in a replica barn, and were also instrumentalised for propaganda purposes: the display was intended to show that humans and animals had supposedly lived “in intimate proximity” to each other in the “older German homesteads”.20 Rustic architecture in the style of northern German farmhouses was a “propagandistic symbol of a connection to the peasant class and the native soil. The carved gable [of a barn] honored the ‘Führer’s’ care for the German farmer. The blood-and-soil ideology here [was] unmistakable.”21

Native livestock were displayed in a replica barn, and were also instrumentalised for propaganda purposes: the display was intended to show that humans and animals had supposedly lived “in intimate proximity” to each other in the “older German homesteads”.20 Rustic architecture in the style of northern German farmhouses was a “propagandistic symbol of a connection to the peasant class and the native soil. The carved gable [of a barn] honored the ‘Führer’s’ care for the German farmer. The blood-and-soil ideology here [was] unmistakable.”21

‘Lower Saxon farmhouse with barn’ in Berlin Zoo, 1937. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

The zoo had previously been organised according to strictly taxonomic principles, see also  Taxonomic Orders. For the first time, the grounds now adopted the previously rejected idea of what was referred to as a ‘geo-zoo’. Instead of arranging the animals according to outwardly recognizable kinships, geography became the guiding principle. As part of National Socialist propaganda, the zoo began displaying animals that lived in the same natural habitat – an idea that had so far been rejected in Berlin. At the center of the ‘German Zoo’, as this section was called in the zoo’s publications, was an enclosure for a special species of cattle called the auroch or urus. Aurochs, which were considered the progenitor of all European breeds of domestic cattle, had, however, been extinct since the death of the last member of the species in the 17th century. Lutz Heck and his brother Heinz, director of Munich’s Hellabrunn Zoo, attempted to resurrect these animals by cross-breeding different species of cattle.22

Taxonomic Orders. For the first time, the grounds now adopted the previously rejected idea of what was referred to as a ‘geo-zoo’. Instead of arranging the animals according to outwardly recognizable kinships, geography became the guiding principle. As part of National Socialist propaganda, the zoo began displaying animals that lived in the same natural habitat – an idea that had so far been rejected in Berlin. At the center of the ‘German Zoo’, as this section was called in the zoo’s publications, was an enclosure for a special species of cattle called the auroch or urus. Aurochs, which were considered the progenitor of all European breeds of domestic cattle, had, however, been extinct since the death of the last member of the species in the 17th century. Lutz Heck and his brother Heinz, director of Munich’s Hellabrunn Zoo, attempted to resurrect these animals by cross-breeding different species of cattle.22

One of the cattle resulting from Lutz Heck’s backbreeding efforts, around 1930. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

Lutz Heck wanted to create an archetypal German animal that would be “a true symbol of German strength and courage”.23 In his publications, Heck repeatedly referred to the Song of the Nibelungs, which also features Siegfried’s hunt for aurochs.24 But the Heck brothers failed. They lacked genetic material, and thus managed only to create a breed that was at most an auroch look-alike or back-breed, in which the external characteristics of the animal species are approximately reproduced. Many of their colleagues viewed the attempt as unscientific even then, and it is still regarded as such. Lutz Heck nonetheless instrumentalised his ‘aurochs’, even managing to use cattle to serve the Nazi propaganda purposes.

Having the zoo conform to National Socialist propaganda paid off for Lutz Heck. He became a member of the NSDAP on 1 May 1937, immediately after the 1933 admission ban was lifted.25 Membership was only possible for those who, despite not belonging to the party, had rendered outstanding services to it. In the summer of 1938, Reichsforstmeister Göring even appointed Heck head of the Oberste Naturschutzbehörde, the highest nature conservation authority in the Reich.26

Jewish Shareholders and Visitors

The Zoo’s implementation of National Socialist and racist policies also had consequences for the Jewish people who supported the zoo as visitors and shareholders. The rapidly increasing anti-Jewish laws that began stripping Jews of rights and property from 1933 onwards forced them to liquidate their assets just to survive. Fleeing Germany often required extensive financial resources. Shares in the zoo thus also had to be sold.

However, the zoo shares had never been speculative stocks. They did not promise a distribution of profits. Free admission for family members served, in a manner of speaking, as shareholders’ dividends. But of course the price of a zoo share fluctuated over the years, and a sale could result in profit or loss. For many Jewish Berliners, shares in the zoo, which had often been in the family for decades, were of great sentimental value. They were associated with a long tradition of Jewish patronage in Berlin, which demonstrated the shareholders’ membership in the Berlin bourgeoisie. Many visited the zoo regularly, some even daily.27 Some Jewish shareholders had still been able to sell at market price before 1938. However, the increased supply of shares for sale, and the weakened position of the sellers increasingly caused prices to fall.

According to the statutes of the shareholders’ association, there were no legal controls over who bought the shares, nor did the zoo have to consent to a sale. Although the zoo shares were registered shares, since they were linked to a right of admission, shareholders were only entered in the zoo’s share register after the sale. This was a thorn in the side of the Supervisory Board. In the spring of 1938, it thus planned to amend the association’s statutes to give the zoo the right of approval for all sales. This would have allowed the zoo to exclude Jewish buyers, and to exert pressure on both sides to lower the sales price. The Board ultimately refrained from following through on this plan for legal reasons, since the amendment to the statutes would also have affected non-Jewish shareholders, who in turn would have had to consent to the change. In the minutes of the meeting, this was recorded as follows:

“The proposal of the Board of Directors to amend Section 3 to the effect that the transfer of shares be made dependent on the consent of the company, in order to gradually eliminate the non-Aryans among the shareholders, is, in the opinion of our legal counsel, unfortunately impracticable, because […] in the case of already existing companies, the consent of all shareholders concerned is required.”28

In July 1938, however, the Supervisory Board decided to acquire the legally permitted ten percent of its own shares from Jewish shareholders. After the November pogrom of 1938, the last remaining Jewish shareholders tried to sell their shares. The zoo itself purchased about 100 shares from Jewish shareholders and passed them on to ‘Aryan owners’.29 The small number of interim sales documented during this time show that the zoo tried to make a profit on these transactions by buying at low cost and selling at a higher price.30

Once Jews had been virtually excluded from being shareholders of the zoo, the Supervisory Board sought to exclude them as visitors, too. At the Supervisory Board meeting of 8 November 1938, board member SS-Brigadeführer Ewald von Massow proposed that Jewish children be banned from playing in the common playground. The Board also decided that for the coming Christmas celebrations, notices should be placed on the nativity scene set up in the zoo to indicate that Jews were not welcome there. The minutes of the meeting read:

“[…] these signs could then be officially placed at all entrances on 1 January.”31

The following night, across Germany National Socialists murdered hundreds of German Jews, destroying livelihoods and synagogues in an organised pogrom. The Nazis blamed German Jews for these planned and centrally coordinated acts of violence. In the days that followed, the Berlin police chief banned them from visiting places of entertainment. Official government policy preempted the measures planned by the zoo management. The zoo had always identified itself as an educational institution. Now it excluded a group of visitors whose place in the German nation (‘Volk’) had been negated by racist ideology and persecution.

The Zoo During the War

During the war, Berlin Zoo and its director were to reap the rewards of having consistently accommodated National Socialist policies. Privileged status was signalled, for instance, by the fact that at the beginning of the war, the zoo was classified as “important to the war effort” and individual male employees could thus be exempted from military service. On 14 September 1939, shortly after Germany invaded Poland, Hermann Göring decreed that zoological gardens were to remain open during the war in order to continue providing popular education for the ‘Volk’.32 Zoos represented a distraction for the public, which was desired by the regime. The extent to which Lutz Heck had influenced Göring in the making of this decision can no longer be gleaned from the available records.

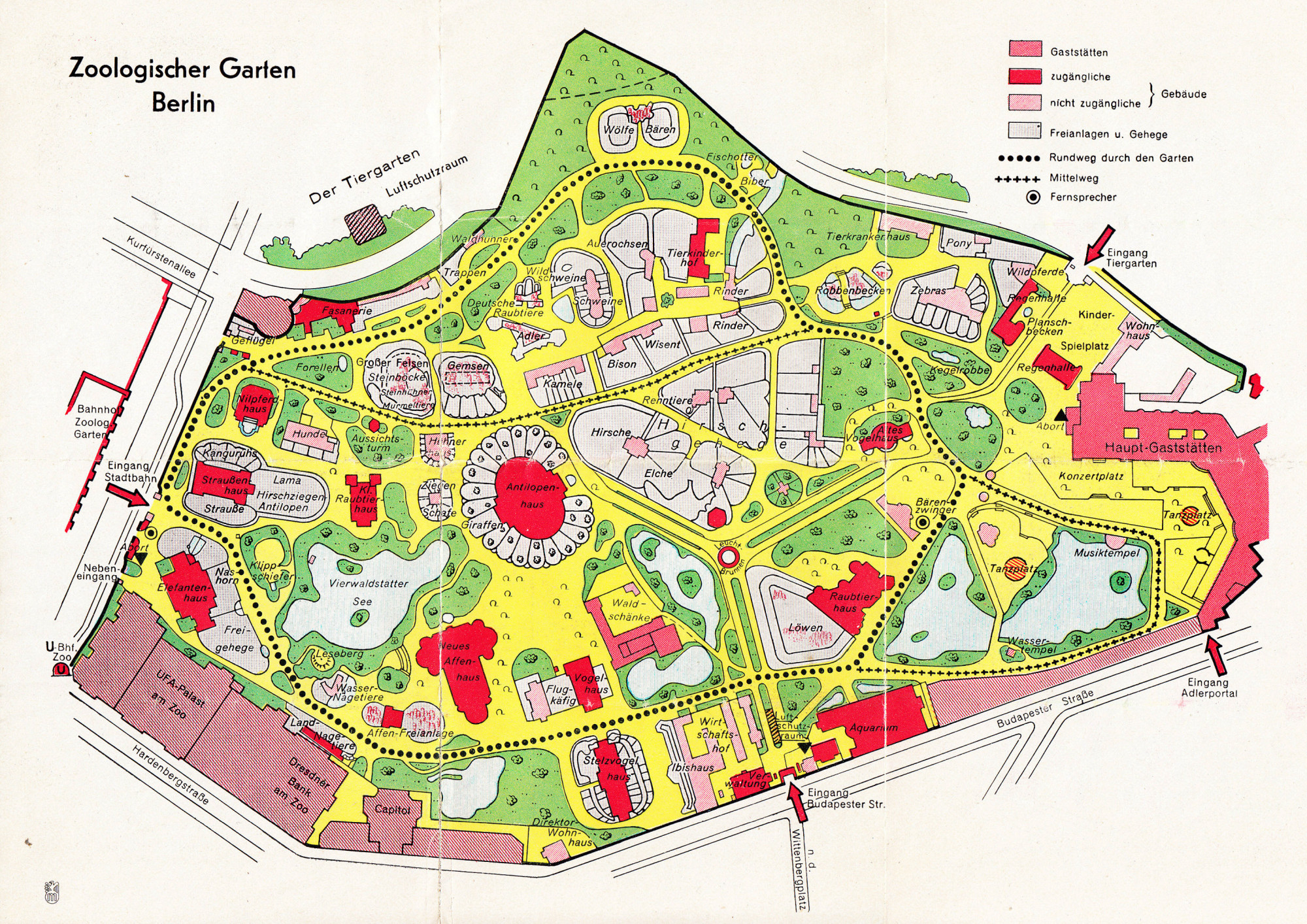

An air-raid shelter for visitors and employees was built in the middle of the promenade under the flowerbeds at the Elephant Gate entrance.33 And from the spring of 1941 onward, the huge ‘Zoobunker’ flak tower, capable of providing shelter for several thousand people, was located to the north of the zoo.

Site plan of the zoo around 1940. Air raid shelters are marked at the south entrance on Budapester Straße, at the Elephant Gate, and to the northwest of the zoo. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

The new Steinbockfelsen, or Ibex boulder, completed in 1938, were designed so that the interior could be used as an air-raid shelter. It was however not considered gastight and therefore not officially used for that purpose.

There were plans to construct an air-raid shelter for 150 people under the Steinbockfelsen, built in 1938. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

In addition, the zoo developed an emergency response plan to capture or kill animals should they try to escape in the event of a bombing. The zoo also established its own fire department staffed by zoo personnel. Members of staff armed with nets and rifles were to man lookouts in earth bunkers, tasked with intervening should animals escape during a bombing raid. Other zoos later adopted similar emergency protocols. In Berlin, as well as preventing escapes, these plans averted the preemptive killing of predators and other animals considered dangerous. Stories about zoo animals running across the Kurfürstendamm can be safely relegated to the realm of myth.34 In London Zoo, whose population suffered under the German bombing campaign during the ‘Blitz’, poisonous snakes and spiders were killed as a precaution, along with other similar measures, including the shooting of predators in the event of an escape. Aerial warfare against the civilian population thus meant that zoo animals previously perceived as safe once again became potentially wild and dangerous creatures.35 But beyond this, the war caused a paradoxical reversal and extension of the zookeepers’ role: where once their work had been primarily curative, war conditions now added a potentially  lethal dimension. Ideological warfare intruded into the relationship between caregivers and those they were tasked with caring for.

lethal dimension. Ideological warfare intruded into the relationship between caregivers and those they were tasked with caring for.

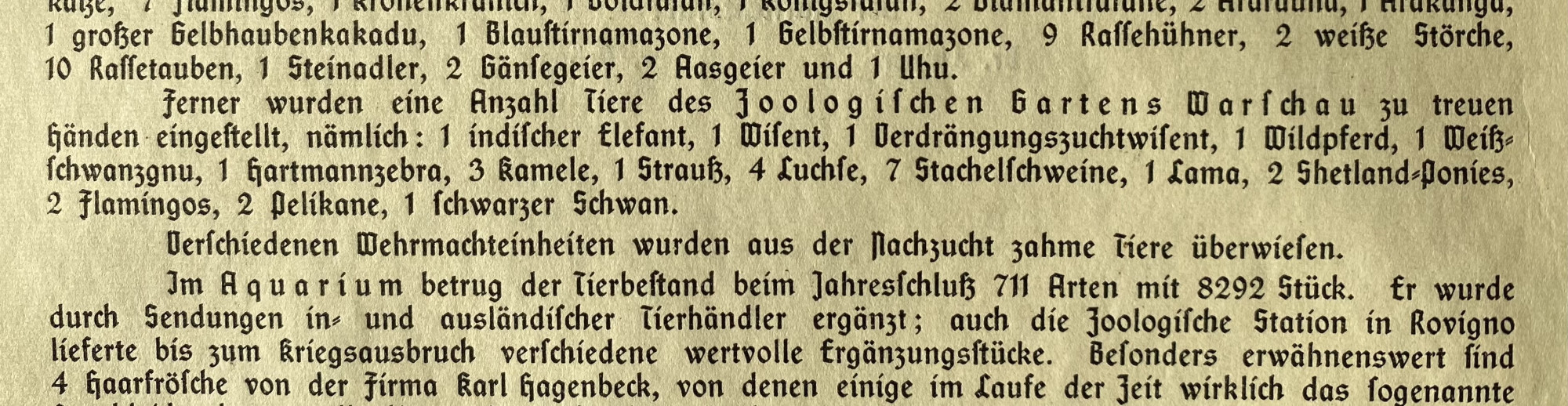

Many of the zoos in the countries conquered by Germany did not enjoy the protected status that Berlin Zoo did, and thus fared less well. According to the memoirs of Antonina Żabińska, wife of Warsaw Zoo director Jan Żabiński, Lutz Heck came to Warsaw immediately after the city’s occupation and ordered the most beautiful animals to be transferred to other zoos in the territory of the Reich. He then initiated the liquidation of the Warsaw Zoological Garden at the request of the National Socialist regime.36

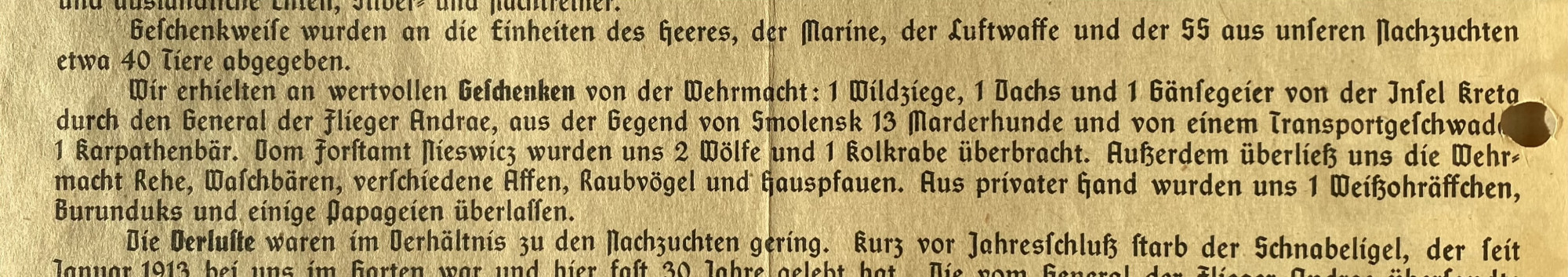

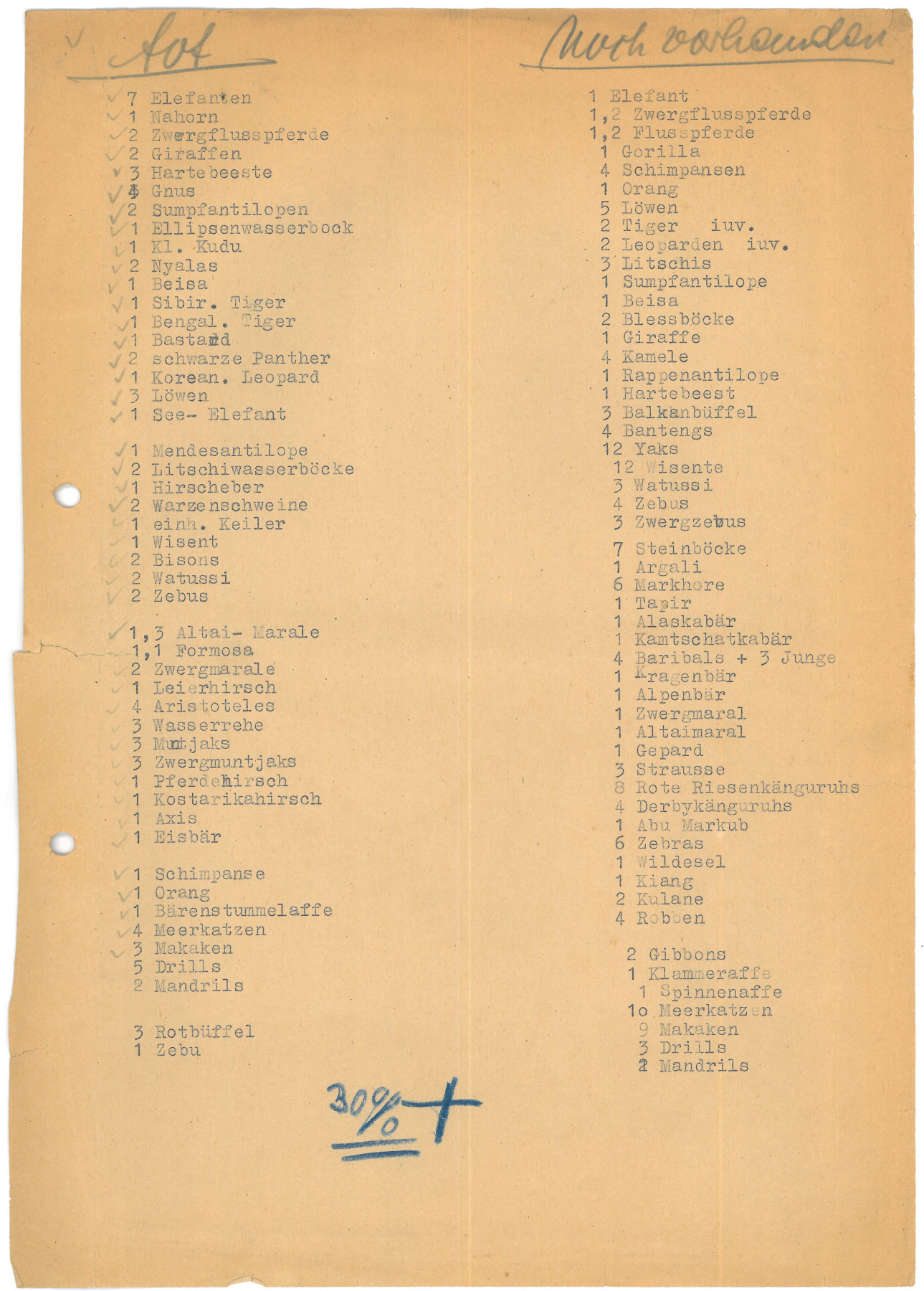

Excerpt from the annual report of 1939. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

From 1939 on, the zoo also enjoyed the spoils of war from other sources. The SS Schutzstaffel (SS) provided it with Polish Konik, or ‘Panje horses’ in 1940. Similar to their endeavors with the aurochs, Lutz Heck and his brother Heinz, the zoo director at Munich Zoo, attempted further crossbreeding in an effort to breed back the extinct species of horse known as the tarpan.37

Excerpt from the annual report of 1942. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

By the time Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, Lutz Heck had risen to the position of director of the nature conservation department of the Reich Forestry Authority (Reichsforstamt). This agency coordinated the evictions and pogroms that took place in the last remaining European primeval forest of Białowieża. Reichsjägermeister Hermann Göring intended this expansive area to be used for hunting bison and the ‘aurochs’ which had not yet been released into the wild. Hundreds of Jewish people were murdered in the course of the evictions, and thousands of non-Jewish Poles were displaced. The fact that two Polish researchers set out in search of stolen Koniks horses in Berlin after the war suggests that Lutz Heck probably also had horses stolen from this forest.38

Lutz Heck (left) and probably his driver in front of the service vehicle of the Reich Hunting Authority (Reichsjagdamt), 1939. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

Although the zoo was under explicit instructions to remain open, like all other zoos in the Reich’s territory, it was affected by the conscription of employees to the Wehrmacht. To replace its workforce, from 1940 onwards the zoo exploited forced laborers, using first Polish and French, and later probably also Soviet prisoners of war and civilians. A speech given by the administrative director at a shareholders’ meeting suggests that Lutz Heck himself had six young men deported to Berlin during a visit to Białowieża in 1941, so that they could work for him as forced laborers.39 Evidence also indicates that the zoo exploited an unknown number of what were referred to as ‘Ostarbeiter’, workers from the East, in the late summer of 1941. These were people who had been kidnapped or lured from the occupied Soviet Union to Berlin under false pretences. At least one Dutch prisoner was forced to work at the aquarium. In the last year of the war, they were joined by 40 Italian military internees – Italian soldiers interned after Italy’s surrender. In 1943, the zoo planned to build a barrack to accommodate approximately twelve forced laborers. Several hundred Soviet prisoners of war from the Berlin administrative division were also deployed at the zoo during the clean-up work after the bombing raids in the winter of 1943/44. We know little about the living conditions of those who were forced to work at the zoo. There is evidence that forced laborers were also used in other German zoos, but it seems likely that the zoo in the Reich’s capital was particularly well served by the allocation of forced labor.40

The zoo also benefited in other ways from the connections of its director and Supervisory Board. These networks were cultivated throughout the war. As pictures in the zoo archives show, Hermann Göring visited Berlin Zoo as late as 1942.

Hermann Göring (center, light-colored coat) on a visit to Berlin Zoo in 1942, speaking with Lutz Heck (center, dark-colored coat). (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

The regime also supported the zoo with animal feed. In his role at the Reichsforstamt in Berlin, Lutz Heck coordinated the supply of feed to zoos throughout the Reich. He was very successful in this: up until the last months of the war, rare seabirds and seals were still being supplied with ocean fish.41

Destruction

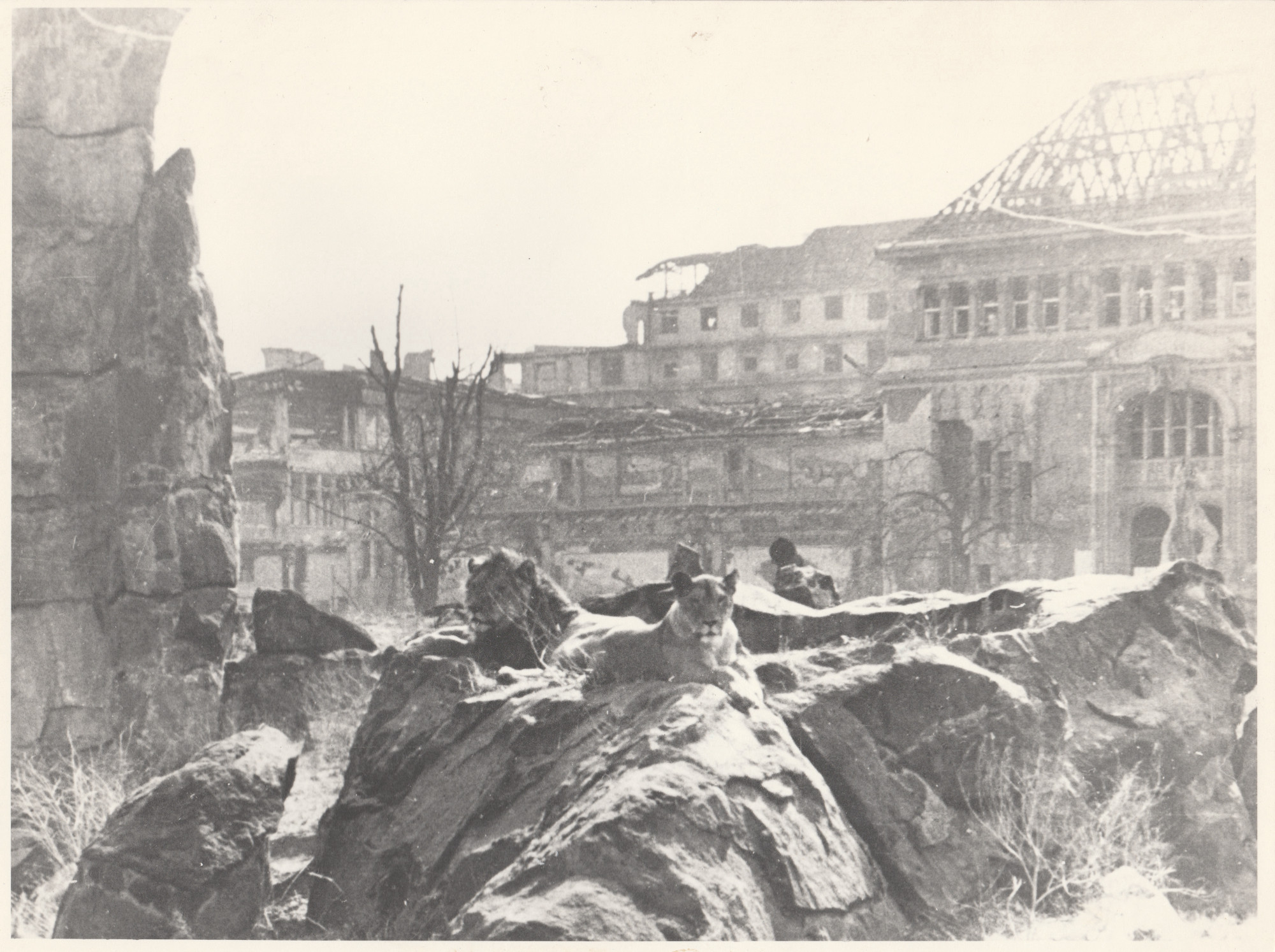

On the night of 23 November 1943, an Allied bombing raid turned the zoo into a sea of flames, and killed 30 percent of the remaining animals.42

List of Dead Zoo Animals, 1943. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

List of Dead Zoo Animals, 1943. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

The aquarium was destroyed the following night. A bomb hit in the middle of the central crocodile hall. Vast quantities of water washed the animals through the shattered windows of the aquarium and down to the street and adjacent zoo grounds. The cold-blooded reptiles and snakes immediately froze in the cold November night. Some caimans could still be recovered alive on the first floor. Oskar Heinroth and the remaining staff tried to keep them alive in the boiler room, but failed in their efforts. In the zoo itself, bomb damage had also allowed some animals to escape from their enclosures. The emergency measures that had been prepared were put into effect. The animals were captured or killed.

Interior of destroyed elephant enclosure, in which seven elephants died, 1943. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

Hundreds of forced laborers cleared the zoo of debris.43 Half a year later, the zoo reopened in time for its centennial celebration on 25 July 1944. It allowed entry to as many as 5,000 people at a time during its opening hours in the summer and autumn of 1944. A total of 250,000 visitors came to marvel at the zoo’s population, which still comprised more than 1,500 animals.44 In the event of an air-raid alert, visitors were to be evacuated to the enormous flak tower on the northern edge of the zoo.45

On 22 April 1945, however, it all finally came to an end. All male employees were drafted into the Volkssturm national militia. They had to dig trenches through the zoo’s grounds. On 30 April, shortly before Soviet troops reached the zoo, the senior management team surrounding Lutz Heck fled.46 For 48 hours, the fierce battle for the neighbouring flak tower also raged on the grounds of the zoo. On 2 May, the battle for the city center and the zoo ended. Corpses and animal carcasses lay everywhere; the city was finally liberated.47

The zoo’s surviving lions in their outdoor enclosure, against the backdrop of the destroyed aquarium, 1945. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

At the end of National Socialist rule, the zoo was no longer the establishment it had been from its beginnings until 1933 – neither materially, nor in its institutional make-up. Berlin Zoo under National Socialism exemplifies how extensively political pressure can shape and instrumentalise the zoo as an institution. Its exhibition of live animals could readily be put to use for Nazi propaganda, and served the aims of the NSDAP in various ways.

Zoos are certainly also compatible with other regimes and social systems – even if this adaptation has often been more subtle and less pronounced. During the Cold War, the East Berlin Magistrate and the SED regime instrumentalised the Berlin Tierpark for cultural diplomacy in the dispute over the international recognition of the GDR. The park served as an internationally recognised example of socialist policy in education and scientific research. Zoos resumed the role they had played in the 19th century when many of them were first founded: they represented a defining  feature of a capital city – or in this case half a city. The West Berlin zoo director could count on West German federal policy to be invested in the zoo’s attraction for the enclosed western half of the city.48 Nowadays, zoos position themselves as centers of species conservation in liberal societies that are increasingly concerned with

feature of a capital city – or in this case half a city. The West Berlin zoo director could count on West German federal policy to be invested in the zoo’s attraction for the enclosed western half of the city.48 Nowadays, zoos position themselves as centers of species conservation in liberal societies that are increasingly concerned with  biodiversity. In none of these cases, however, has the political exploitation of the zoo as an institution been attempted or achieved to the degree reached by the National Socialists.

biodiversity. In none of these cases, however, has the political exploitation of the zoo as an institution been attempted or achieved to the degree reached by the National Socialists.

- Cf., for instance, Ludwig Heck. Heiter-ernste Lebensbeichte: Erinnerungen eines alten Tiergärtners. Berlin: Deutscher Verlag, 1938: 373; Lutz Heck. Der deutsche Edelhirsch: Ein Lebensbild mit photographischen Naturaufnahmen aus der Wildbahn. Berlin: Paul Parey, 1935.↩

- Curriculum Vitae Lutz Heck for the Reichsschrifttumskammer, Bundesarchiv Berlin (BArch), R 9361, V, 5953.↩

- Lutz Heck. Waidwerk mit bunter Strecke: Jagd in heimischen Revieren. Hamburg, Berlin: Parey, 1968: 67.↩

- Cf. Clemens Maier-Wolthausen. Hauptstadt der Tiere: Die Geschichte des ältesten deutschen Zoos. Andreas Knieriem (ed.). Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag, 2019: 111-113.↩

- Cf. Lutz Heck. Auf Urwild in Kanada. Berlin: Paul Parey, 1937.↩

- Cf., for instance, Heck, 1935.↩

- Jahrbuch der Fachschaft Deutsche Bracken, 1935/36.↩

- Zoological Garden Berlin, “Alte Tierkartei”; and list of Hermann Göring’s lions with offspring, AZGB N 5/13.↩

- Minutes of Supervisory Board meeting, 1933, AZGB O 0/2/2.↩

- Actien-Verein des Zoologischen Gartens Berlin. Geschäftsbericht für das Jahr 1933. Berlin: 1934.↩

- Minutes of Supervisory Board meeting, 1933, AZGB O 0/2/2, and memo for Regierungspräsident Zachariae, GStA PK I. HA Rep. 151, Nr. 2496, Bl. 23; minutes of the General Assembly 1934, AZGB O 0/3/2.↩

- Minutes of Supervisory Board meeting, 22.05.1933, AZGB O 0/2/2.↩

- Actien-Verein des Zoologischen Gartens Berlin. Geschäftsbericht für das Jahr 1933. Berlin: 1934.↩

- “Der Urwald ruft: Kolonialkunst-Ausstellung im Zoologischen Garten”. Berliner Lokalanzeiger, 06.04.1933.↩

- The colonised territory of ‘German East Africa’ comprised today’s Tanzania, Burundi, Rwanda as well as some parts of Mozambique.↩

- Press release 29.06.1934, AZGB O 0/1/15; “Sensation im Affenpalmenhaus”. Völkischer Beobachter, 13.06.1937.↩

- Annual reports for the years 1935 and 1936.↩

- Correspondence between all parties in GStA PK I. HA, Rep 151, 2500 and minutes of Supervisory Board meeting, 24.08.1935, GStA PK I. HA, Rep 151, 2496, Bl. 93-94.↩

- Wiebke Reinert and Mieke Roscher. “Der zoologische Garten als anderer Raum: Hamburger und Berliner Heterotopien”. In Urbane Tier-Räume, Thomas E. Hauck, Stefanie Hennecke, André Krebber, Wiebke Reinert, and Mieke Roscher (eds.). Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag, 2017: 112.↩

- Press tour of domestic animal exhibition, Pentecost 1937, AZGB O 0/1/15.↩

- Kai Artinger. “Lutz Heck: Der ‘Vater der Rominter Ure’; Einige Bemerkungen zum wissenschaftlichen Leiter des Berliner Zoos im Nationalsozialismus”. Der Bär von Berlin: Jahrbuch des Vereins für die Geschichte Berlins 23 (1994): 125-139. https://www.diegeschichteberlins.de/geschichteberlins/persoenlichkeiten/persoenlichkeitenhn/491-heck.html (03.01.2022).↩

- Cf., for instance, Lutz Heck. “Über die Neuzüchtung des Ur oder Auerochs”. Berichte der Internationalen Gesellschaft zur Erhaltung des Wisents 3, Nr. 4 (1936): 224-294, 235.↩

- Lutz Heck. Auf Tiersuche in weiter Welt. Berlin: Paul Parey, 1941: 195.↩

- Heck, 1941: 195; and Lutz Heck. “Letzte Urwaldtiere aus deutscher Vorzeit”. Atlantis: Länder, Völker, Reisen 4, Nr. 10 (1932): 577-583; Lutz Heck. “Die Neuzüchtung des Auerochsen”. Wild und Hund 37 (15.12.1939): 535-537. A frieze with a verse from the epic also decorated the aurochs’ stand at the international hunting exhibition of 1938.↩

- Membership card at the Berlin document center of the Bundesarchiv Berlin.↩

- Cf. Transcript of Ministerial Director Ebert’s Reichsforstamt to Federal Director of the Reichsbund für Biologie, the Reich Association for Biology, Dr. W. Greite, 05.02.1941, BArch, NS 21/1543; minutes of Supervisory Board meeting, 19.07.1938, AZGB O 0/2/2.↩

- Monika Schmidt has collected the family histories and stories of persecution of many Jewish zoo shareholders. She repeatedly came across evidence of a sense of bourgeois pride in owning zoo shares. Schmidt, Monika. Die jüdischen Aktionäre des Zoologischen Gartens zu Berlin: Namen und Schicksale. Berlin: Metropol, 2014.↩

- Minutes of Supervisory Board meeting, 29.03.1938, AZGB, O 0/2/2.↩

- Minutes of Supervisory Board meetings, 19.07.1938 and 16.12.1938, AZGB O 0/2/2.↩

- Cession papers in the archive of the Zoological Garden Berlin.↩

- Minutes of Supervisory Board meeting, 08.11.1938, AZGB O 0/2/2.↩

- Minutes of Supervisory Board meeting, 16.12.1939, AZGB O 0/2/2.↩

- Construction drawings and building petitions for air-raid shelters, LAB, A Rep. 032-08, no. 293; cf. also Lutz Heck. Tiere – mein Abenteuer: Erlebnisse in Wildnis und Zoo. Vienna: Ullstein 1954: 97-102; Speech of L. Heck at General Assembly, 1940, AZGB O 0/3/13; note on the annual report for the year 1941, AZGB O 0/3/12.↩

- Cf. Maier-Wolthausen, 2019: 118-129.↩

- Anna-Katharina Wöbse and Mieke Roscher. “Zootiere während des Zweiten Weltkrieges: London und Berlin 1939-1945”. WerkstattGeschichte, Nr. 56 (2010): 44-62, 50.↩

- Gary Bruce. Through the Lion Gate: A History of the Berlin Zoo. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017: 164, with reference to the memoirs of the zoo director’s wife, Antonina Żabińska.↩

- Minutes of Supervisory Board meeting, 30.07.1940, AZGB O 0/2/2.↩

- Cf. Andreas Gautschi. Der Reichsjägermeister: Fakten und Legenden um Hermann Göring. Melsungen: Nimrod, 2010; Heinrich Rubner. Deutsche Forstgeschichte, 1933-1945: Forstwirtschaft, Jagd und Umwelt im NS-Staat. St. Katharinen: Scripta Mercaturae, 1997; copy of the agreement between the headquarters of the Reichskommissar für die Festigung deutschen Volkstums, the Reich Commissioner for the consolidation of German nationalism, and the Reichsforstmeister as Oberster Naturschutzbehörde, head of the highest nature conservation authority, on the execution of the meeting of 20 March 1942, 11.05.1942, BArch, R 49/2066; correspondence with the British Commandant Tiergarten Lt. Col. Nunn in December 1945, AZGB S 15/17; old animal index card, index card “Panjepferde”. (The gendered German word for ‘scientists’ in the original of this article indicates that both scientists were men.)↩

- Minutes of General Assembly, 1942, AZGB O 0/3/12.↩

- Cf. Maier-Wolthausen, 2019: 126-127.↩

- Circular letter L. Heck to the zoological gardens, 22.02.1945; and Fisch-Grosshandel H. D. Petersen to L. Heck, 08.03.1945, AZGB O 0/1/88.↩

- List in AZGB O 0/1/54.↩

- Copy of Lutz Heck’s report to the Supervisory Board, January 1944, AZGB O 0/1/54.↩

- L. Heck: Memo concerning opening on 25.7.1944, AZGB O 0/1/50; recollections of Elisabeth Johst, AZGB S 15/27.↩

- Recollections of Elisabeth Johst, AZGB S 15/27; K. Heinroth to W. Keller, 18.09.1945, AZGB O 0/1/87; K. Heinroth to G. Freytag, 03.01.1946, AZGB O 0/1/86.↩

- Ibid.↩

- K. Heinroth: “Kriegszerstörungen und Aufbau von 1945 bis 1956 im Berliner Zoologischen Garten”, typewritten manuscript, AZGB N 4/2.↩

- Cf. to this Maier-Wolthausen, 2019: 162-169, 206-211; Clemens Maier-Wolthausen. “Ein Zoo für die Hauptstadt”. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte 71, Nr. 9 (2021): 11-17, 14-15; Jan Mohnhaupt. Der Zoo der anderen: Als die Stasi ihr Herz für Brillenbären entdeckte & Helmut Schmidt mit Pandas nachrüstete. München: Carl Hanser, 2017; and Clemens Maier-Wolthausen. Alphamännchen und Herdentiere: Deutsch-deutsche Beziehungen in Tierpark und Zoo Berlin. Berlin: Reimer, forthcoming 2022.↩