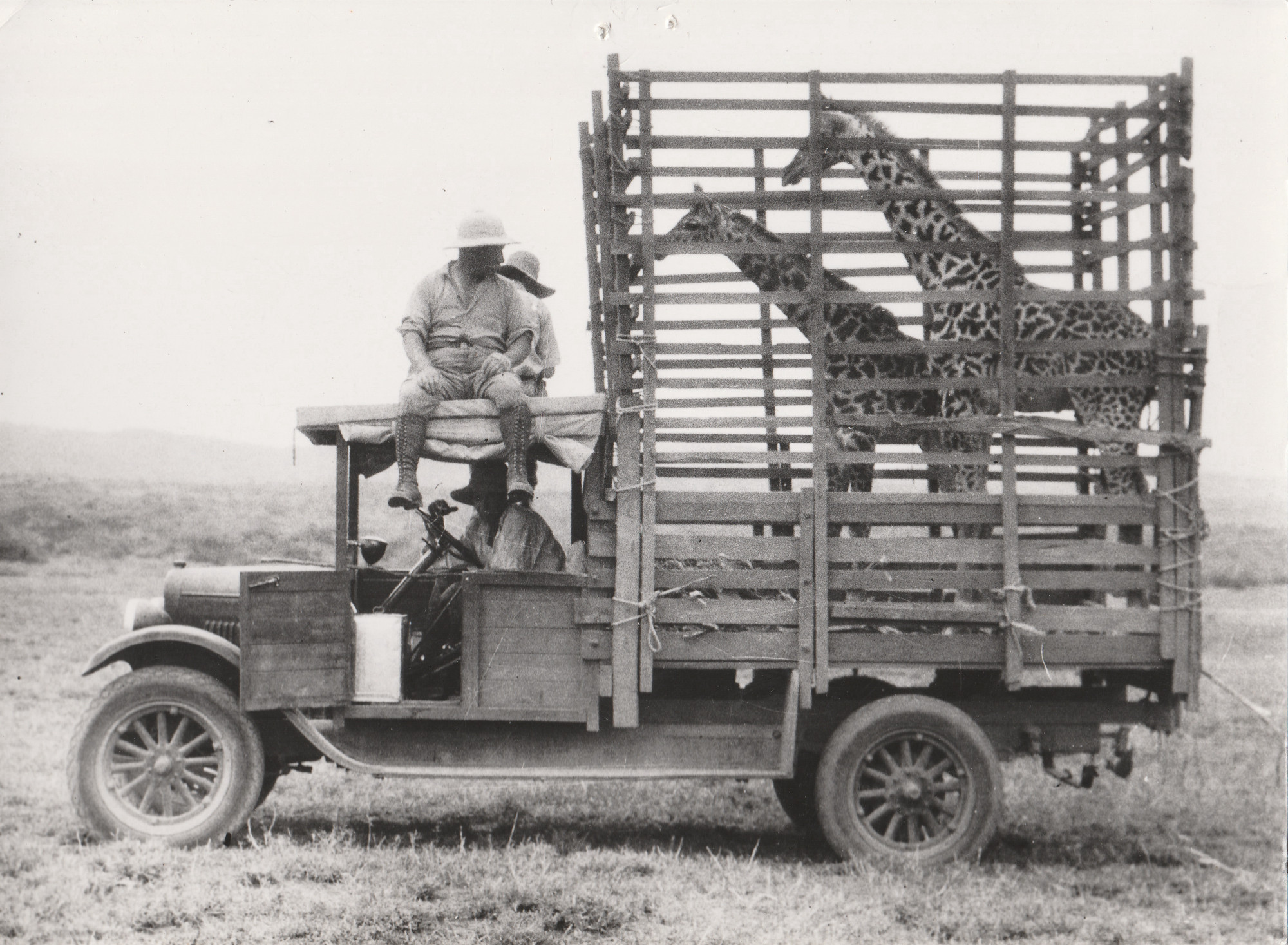

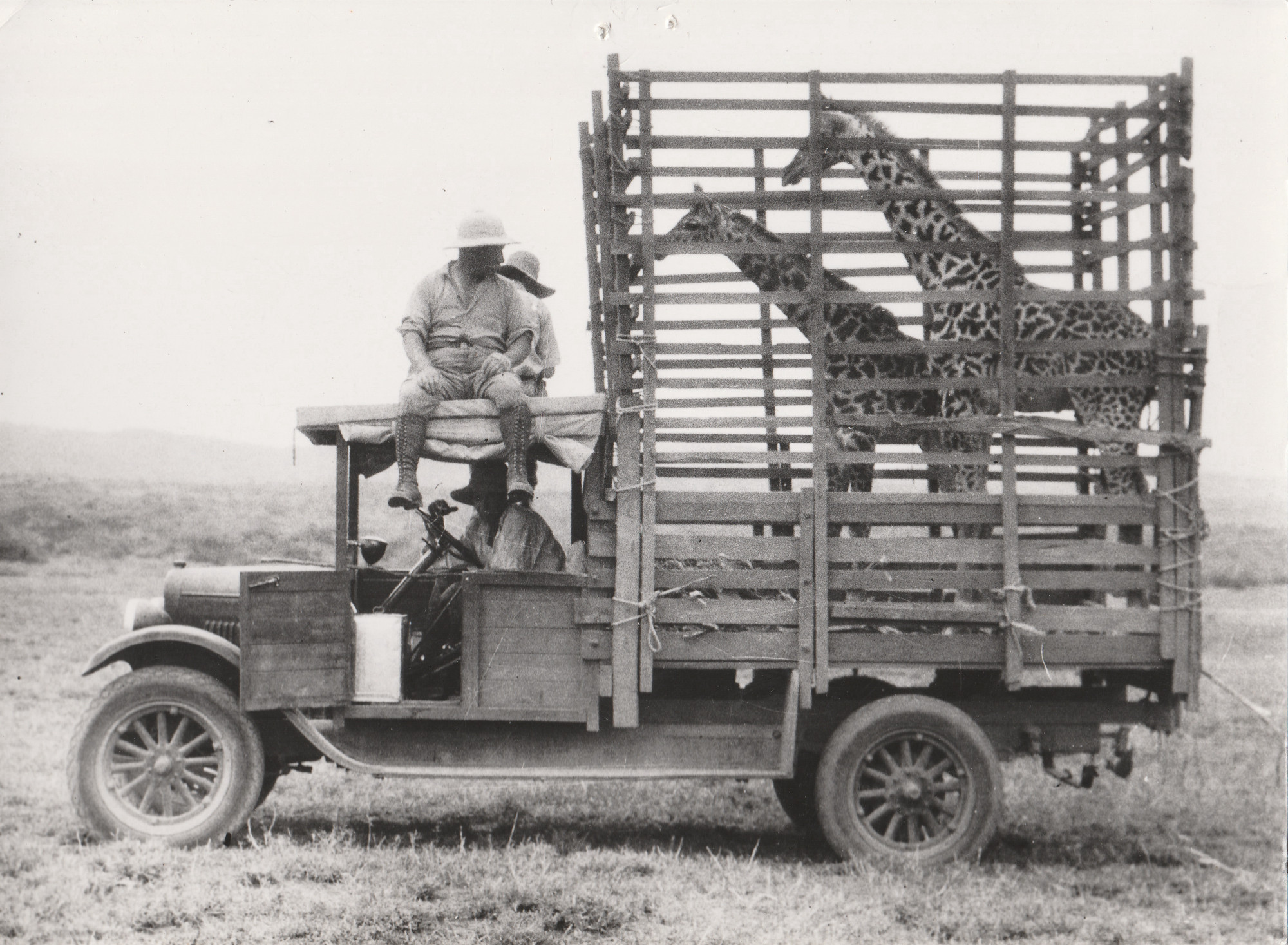

Shipment of two young giraffes, 1928. (AZGB, image: Lutz Heck. All rights reserved.)

In the summer of 1845, the board of the newly founded stock association of the Zoological Garden of Berlin (Actien-Verein des Zoologischen Gartens Berlin) decided to request animal donations from Royal Prussian Consuls in the most significant foreign trading posts and coastal cities. Due to a lack of financial resources, they urgently needed to acquire animals at low cost – especially those not native to Europe and sought after by the public.

“It would be expedient in general to issue the same notification to the Royal Prussian Consuls in the most important commercial and coastal locations, and at the same time to request that they send inexpensively purchased live animals, possibly as a donation for the coming summer. This proposal was duly acknowledged, and its execution agreed on.”1

Though it is no longer possible to ascertain the immediate effects of this request, in 1852, a total of 35 animals – most of them gifts – arrived in Berlin in a shipment from the Prussian Consul General in Cairo, Baron von Pentz.2 These animals had one thing in common with almost all other animals in modern zoos around the world at that time: They had been taken directly from the wild, as had been the case for most of the over 250 years that zoos had been in existence. The establishment of dozens of new zoological gardens in Europe in the second half of the 19th century created a hitherto unprecedented desire for live animals. Animals that were not native to Europe were particularly desirable, as zoo founders expected these would be most captivating for the public. But first, the animals had to be captured. In the first decades after 1850, two types of animal acquisition emerged as particularly prominent: gifts as status symbols, and purchases from  opportunistic traders.

opportunistic traders.

Status Symbols and Gifts

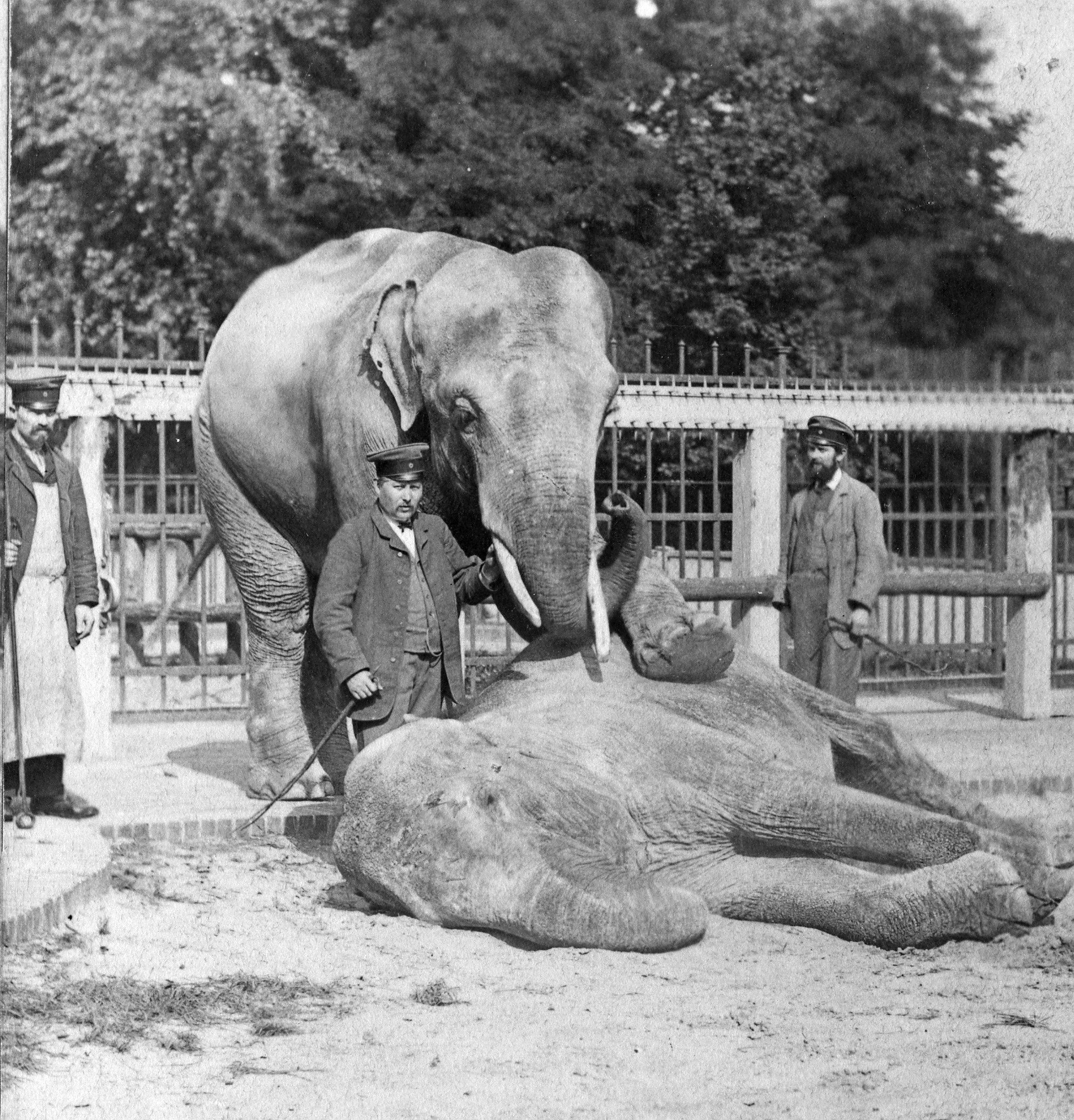

In the 1880s, the Berlin Zoological Garden had two elephant bulls in its possession: “Rostom” and “Omar”. The Prince of Wales, who later became King Edward VII, had given them as a gift in 1881 to his nephew Kaiser Wilhelm II. The elephants originally came from British India, where they had been captured before being transported to Britain.

The two Asian elephant bulls “Rostom” and “Omar”, around 1885. “Rostom”, unusually for the species, had no tusks. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

For a long time, large animals like this were shipped from other continents and climate zones, via a wide variety of routes, to the newly founded zoos of Germany and Western Europe, much like the animals displayed in the so-called travelling, aristocratic, and royal menageries that were the precursors to zoos. Like the animals in the deer parks or bear pits popular in German and Italian courts, many of these animal species served as status symbols for the leaders of their regions of origin. The animals were sold or given to European rulers as gifts.3 The general public in larger European cities had previously encountered such non-native and unusual-looking animals at travelling carnivals, and now demanded to see them in the newly established zoos. However, permanently displaying larger mammals required that a commercial trade in animals be established.

Trade Opportunists

Large mammals were relatively rare in zoos, for a long time being reserved for the domain of state gifts. The history of the animal trade probably began with sailors, captains, and travelling merchants. From about the end of the 18th century, these travellers purchased animals at bargain prices from oversea areas and brought them home to sell when they returned to the ports of Western and Southern Europe. Since small animals were easier to transport, it was predominantly these that arrived in Europe. Among them were parrots and other birds, as well as various species of guenons and monkeys. Common cargo also included smaller predators, and mammals that had been captured young and were accustomed to humans. The care of these animals was not particularly demanding, meaning the travelers could look after them during their time off on ship journeys, which often lasted several months. This form of trade inevitably resulted in the procurement of only a limited range of species, and for the most part involved only individual animals.4

No one knows how many animals died on the long sea voyages, how many were slaughtered or – when they could no longer be cared for – thrown overboard. However, the growing interest in preserving and caring for animals was most likely caused by increased demand and rising profitability. Stables sprang up in ports where the incoming animals could be sold, early examples of which were to be found in London and Amsterdam. For the directors of Europe’s newly established zoos, these two cities became essential for the acquisition of animals. Moreover, after 1870, the ‘Vente publique’ of the Societe Royale d’Anvers in Antwerp became a regular annual event. Many directors travelled to the fair, which involved two days of animal auctions, in order to obtain animals for their zoos.5

Colonialism as a Precondition

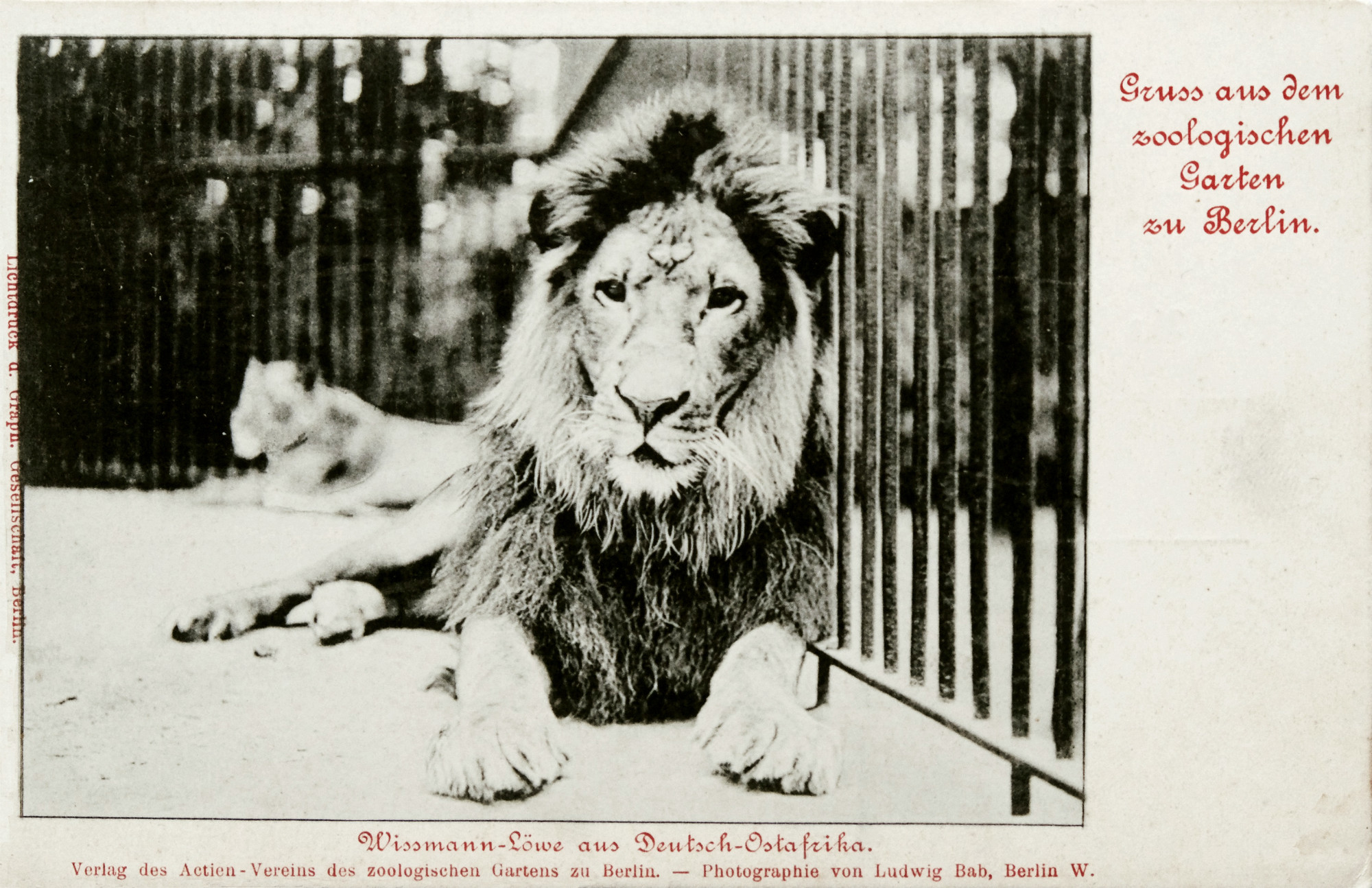

The fact that these port sales and auctions were always full and that state gifts were on the rise had a lot to do with European colonial expansion. The exhibition of significant numbers of non-European wild animals in newly established zoos was inextricably linked to European expansion and imperialism. Colonialism’s violent foundations and military infrastructures were necessary preconditions for the bargain purchases, the hunting of animals, their transportation to Europe, and their subsequent exhibition. It was often the colonial officials themselves who hunted animals in order to give them as gifts. This is illustrated by the example of the lion that the governor of German East Africa, Hermann v. Wissmann, donated to Berlin Zoo in 1896. (The colonised territory of German East Africa comprised today’s Tanzania, Burundi, Rwanda as well as some parts of Mozambique.)

Postcard showing a lion from the German colony of Deutsch-Ostafrika or German East Africa, gifted to Berlin Zoo by Hermann v. Wissmann in around 1900.

Wissmann, known even in Germany for his cruelty toward colonised peoples, donated two further lions to Berlin Zoo, in addition to the one pictured, making one male and two females altogether. The postcard produced by the zoo to mark the occasion shows only the male animal, possibly because his mane made him more imposing, and thus better suited for publicity purposes. Explicitly designating the animal as the ‘Wissmann Lion from German East Africa’, the zoo made itself part of the colonial project, thus contributing to the perpetuation of the colonial agenda. The value of the gift was twofold: first, the animals were valued at 3,000 German marks and recorded as assets in the zoo’s inventory, and second, the zoo profited from colonial exploitation through the advertising appeal of the ‘German East African lion’ and its patron, who had been elevated to the status of nobility by Kaiser Wilhelm II.6 From approximately 1890 to 1914, Berlin Zoo received gifts from German administrators and merchants in the German colonies every year.7

Zoos in all colonizing nations profited from the exploitation of European overseas territories. Animal trading houses such as Jamrach, Hagenbeck, and Reiche also profited from colonial conditions in Africa, Asia, and Oceania. Colonial officials largely prevented the peoples of the occupied regions from making use of their own country’s resources – often through force. Yet colonial administrators did grant licenses to trading houses to capture regional fauna.

The establishment of a colonial infrastructure also facilitated animal transportation for hunters, and later trading houses, as well as enabling communication with potential clients. In the colonies, racial hierarchies and power relations based on violence ensured that animal traders and trappers were able to rely on local people for the difficult and life-threatening work, as well as for the actual hunting expeditions.8

Initially, hardly any professional animal traders were active in the German colonies. According to Carl Georg Schillings, himself a hunter and animal trapper, this was due to the poor transportation routes and the generally less than optimal climate there. He described the situation in 1905 as follows:

“It has not been possible to get any kind of regular import of live animals off the ground, whether from German East Africa or Southwest and West Africa. What the well-known animal importer Menges has often succeeded in doing in Somaliland – an infinitely healthier territory, where camels and horses can live – namely, the organization of regular export of foreign animals, has still not been instigated in any of our colonial territories.”9

For Schillings, this finding called for German capital and commitment, since the regular export of animals from the German colonies would benefit both scientific development and the “national interest”.

High Cost and High Risk

It is important to keep in mind that in order to capture dangerous and herd mammals, trappers often killed other herd members and dams to safely obtain the sought-after young animals. These were much easier to catch and transport than adults. The above-quoted hunter and trapper Georg Schillings had caught a rhinoceros for Berlin Zoo and had shot the animal’s mother to do so. Killing a rhinoceros cow did not, however, guarantee success. As Schillings later related in a book he wrote, the young animals might still make good their escape under certain circumstances.10 The zoo purchased the rhinoceros by means of an additional budget of 20,000 Reichsmark approved by the supervisory board. However, according to the 1908 annual report, the animal died four years later of “sepsis following smallpox”.11

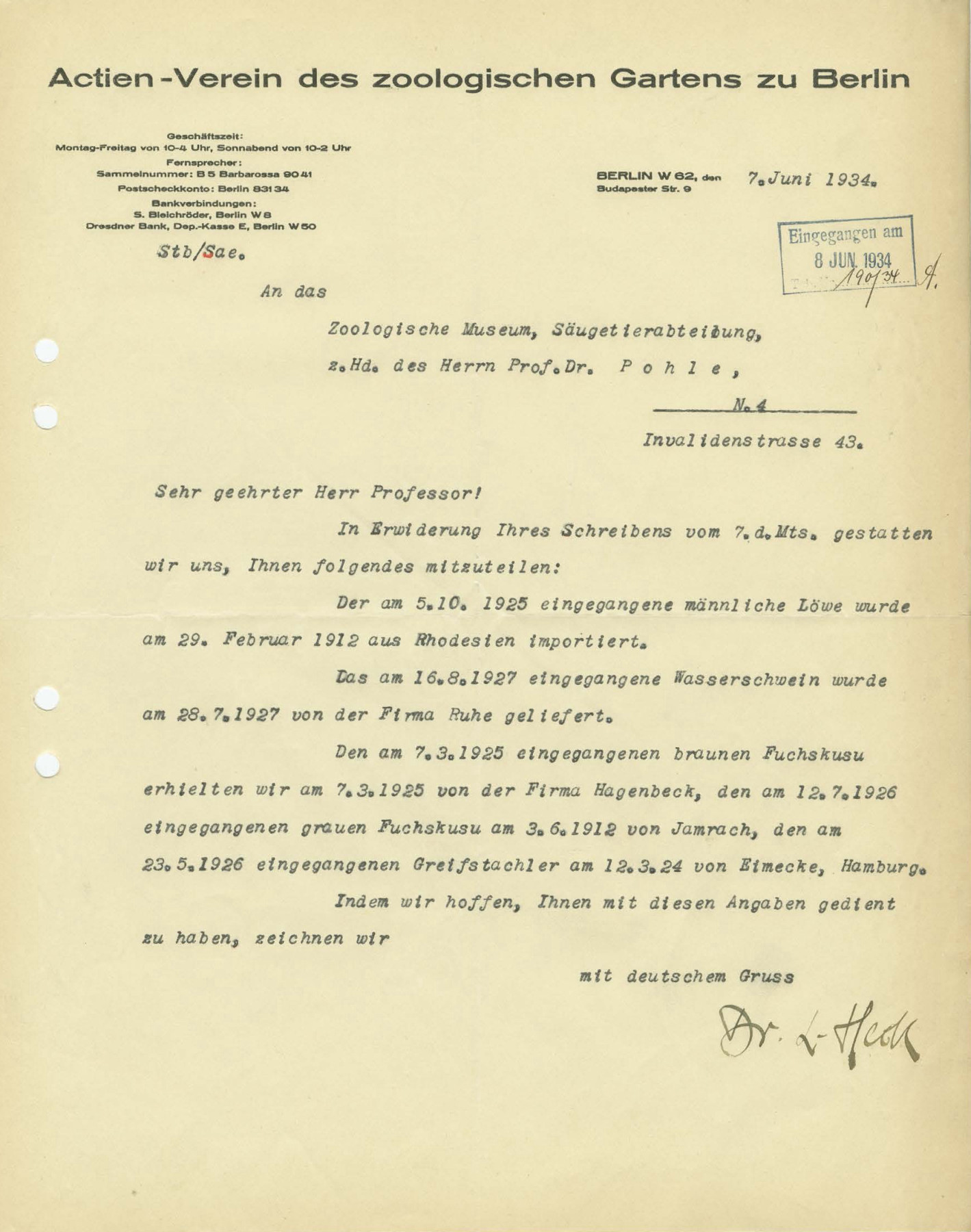

Transportation was a major risk for animal traders, as the animals could die or fall ill en route. We do not have an accurate record of how many animal lost their lives, but it is reasonable to assume that, in the 19th century in particular, mortality was high. Captured animals would initially have to be kept in cages, enclosures, snares, or chains until the expedition was completed or the desired number of animals had been collected. The subsequent hardships of a long journey sometimes led to the animal dying soon after arrival in the zoo itself. A report from Berlin Zoo to the Natural History Museum in Berlin detailing the delivery of  animal carcasses demonstrates this.

animal carcasses demonstrates this.

Zoo director Lutz Heck to Hermann Pohle, the curator of mammals at the National History Museum in Berlin, 07.06.1934. (MfN HBSB S004-02-05 Nr. 97. All rights reserved.)

Two of the four animal carcasses listed for the Natural History Museum were from animals that had recently been delivered by animal traders.

The Big Players: Hagenbeck and Co.

Grouping large shipments was one way of mitigating risk. Although zoo collections were enhanced by gifts from colonial officials, individual catches, and imports by sailors, it took a further development to satisfy the demand of Europe’s and North America’s zoos in the long term. The emergence of professional animal trading companies was instrumental, with the companies Hagenbeck, Reiche, Ruhe and Jamrach at the forefront. It was these commercial animal traders who, by means of large animal shipments, facilitated a steady supply of animals for the display of a large number of different species.

“Although zoos received some of their animals through donations, exchange, or loans, they could not have come into existence, and their collections could not have taken the shape that they did, without the commercial trade in wild animals that provided a reliable supply of polar bears in San Antonio, prairie dogs in Philadelphia, or zebra in Denver. Without animal trade, very few zoos could have displayed more than deer and birds – they would never have become ‘real’ zoos with elephants.”12

Like the bargains purchased by European merchants and the gifts given by colonial officials, the commercial animal trade was premised on colonial dominion over the animals’ habitats. And although the German Reich became a colonial power at a relatively late stage, it was a Hamburg company – Carl Hagenbeck – that played a key role in the animal trade as early as about 1880.

Long before the German Reich had its own colonies, companies such as Hagenbeck, and later Reiche from Alfeld, were capturing African and Asian animals for the purposes of international trade in the British, French, Dutch, and Belgian colonial empires. In 1864, Hagenbeck joined forces with the Austrian animal catcher Lorenzo Casanova in British Sudan. Casanova built a keeping station for Hagenbeck near Kassala, halfway between Khartoum and the Red Sea coast. After Casanova’s death, Hagenbeck maintained this business model and hired permanent agents or sales representatives, like Joseph Menges – as mentioned above by C. G. Schillings. As per the latter’s description of the prevailing division of labor in Kassala, this entailed the (European) trader living in relative comfort, while Sudanese workers brought the animals to the ‘front door’.13 The traders themselves were never or only very rarely actively involved. They relied on local workers or nomadic people, who usually did the physical work of hunting, catching, as well as caring for the animals in the collection and keeping stations. These workers also accompanied the shipments to the ports and sometimes even all the way to their destination. Although the colonial traders and trappers depended on the many people described here, European memory culture very rarely names them; Europeans did not value their work. In images of African hunters and animal caretakers, they are for the most part depicted as mere anonymous carriers.14

Alongside Hagenbeck, the companies Reiche and Ruhe from Alfeld were also major players in the international animal trade. After the turn of the 20th century, Ruhe ran collection and acclimatisation stations near Dire Dawa in present-day Ethiopia and near Nice in France. It was via Nice that the gorilla  “Bobby” came to Berlin.15 The international trade in wild animals was “perhaps the only area of colonial trade that was dominated by Germans”.16

“Bobby” came to Berlin.15 The international trade in wild animals was “perhaps the only area of colonial trade that was dominated by Germans”.16

The business of catching and trading in animals was profitable due, among other things, to the conditions in the zoos themselves. In the enclosures, which were often far too small, a lack of veterinary and ethological knowledge led to high mortality in zoos. There was barely a single animal that could behave anything like it would in the wild, and the feed given frequently did not correspond to the animal’s needs. As a result of such ignorance, some carnivorous animals were given only vegetarian feed, while herbivores were given meat.17 Breeding was not possible, because the zoo sometimes kept only single individuals of a species – though it was arguably not necessary anyway, since the animal trade provided a constant supply of new animals. The only limit was what the zoo could afford. The lifespan of zoo animals was also usually shorter than it would have been in their natural habitat.

At the beginning of the 20th century, a few zoos also organised or financed their own expeditions to acquire animals. For London Zoo, and especially for U.S. zoos, these expeditions were more than just a source of new animals. The Bronx Zoo in New York and the National Zoo in Washington, and later also London Zoo, used the expeditions as marketing opportunities by producing publications about the trips.18

Berlin Zoo conducted its own expeditions to capture animals, albeit few in number. In the 1920s and 1930s,  Lutz Heck, who would go on become zoo director, organised three such expeditions. In addition to supplying animals, they primarily served as a means of self-promotion. Although Heck brought large numbers of animals back to Berlin, it is possible that these could have been purchased more cheaply via the animal trade. For the most part, the trips were used as a form of self-promotion for Lutz Heck and the zoo. Heck used the photos and film footage he gathered for extensive publications, full-length films, and lectures.19 These publications reiterated and reinforced prevailing stereotypes about the people from the regions of the world where the animals had been captured.

Lutz Heck, who would go on become zoo director, organised three such expeditions. In addition to supplying animals, they primarily served as a means of self-promotion. Although Heck brought large numbers of animals back to Berlin, it is possible that these could have been purchased more cheaply via the animal trade. For the most part, the trips were used as a form of self-promotion for Lutz Heck and the zoo. Heck used the photos and film footage he gathered for extensive publications, full-length films, and lectures.19 These publications reiterated and reinforced prevailing stereotypes about the people from the regions of the world where the animals had been captured.

Shipment of two young giraffes, 1928. (AZGB, image: Lutz Heck. All rights reserved.)

Last Hurrah: The 1950s

After the Second World War, Berlin lay in ruins. It was no longer possible to purchase the big cats and large mammals from Africa and Asia that were so adored by the public. The hunt had to take place on native soil. In order to fill the empty enclosures, the director of Berlin Zoo during the reconstruction years,  Katharina Heinroth, obtained animals from a disbanded circus and acquired native animals caught in the forests in and around Berlin. It was not until the mid-1950s that the international animal trade began to thrive once again. Although the trading companies Hagenbeck and Ruhe did not reattain the near monopoly on the animal trade they had enjoyed for many decades, Europe’s war-torn zoos did turn to them to fill their empty enclosures once more.20 According to former zoo director Bernhard Blaszkiewitz, there was a real rush on gorillas around 1960 – and not only at Berlin Zoo, where they had recently finished building the ape house.21 Between 1957 and 1968, the Berlin Zoological Garden received four male and four female gorillas captured in the wild.22

Katharina Heinroth, obtained animals from a disbanded circus and acquired native animals caught in the forests in and around Berlin. It was not until the mid-1950s that the international animal trade began to thrive once again. Although the trading companies Hagenbeck and Ruhe did not reattain the near monopoly on the animal trade they had enjoyed for many decades, Europe’s war-torn zoos did turn to them to fill their empty enclosures once more.20 According to former zoo director Bernhard Blaszkiewitz, there was a real rush on gorillas around 1960 – and not only at Berlin Zoo, where they had recently finished building the ape house.21 Between 1957 and 1968, the Berlin Zoological Garden received four male and four female gorillas captured in the wild.22

Colonial authorities and the governments of now independent former colonies were, at this point, still willing to issue trapping licenses. Zoo director Katharina Heinroth flew to Borneo and Sumatra in 1955. This was not a traditional trapping expedition, as Heinroth had previously received quotes from private individuals and applied to local authorities for capturing and export permits. She came primarily to see the animals in the wild and select specimens. Katharina Heinroth used her personal vacation for this trip and, accompanying the animals on their journey to Berlin, brought a shipment back to the Berlin Zoo.23

Katharina Heinroth upon her return with the rhesus monkey “Putzi” on her shoulder, 1955. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

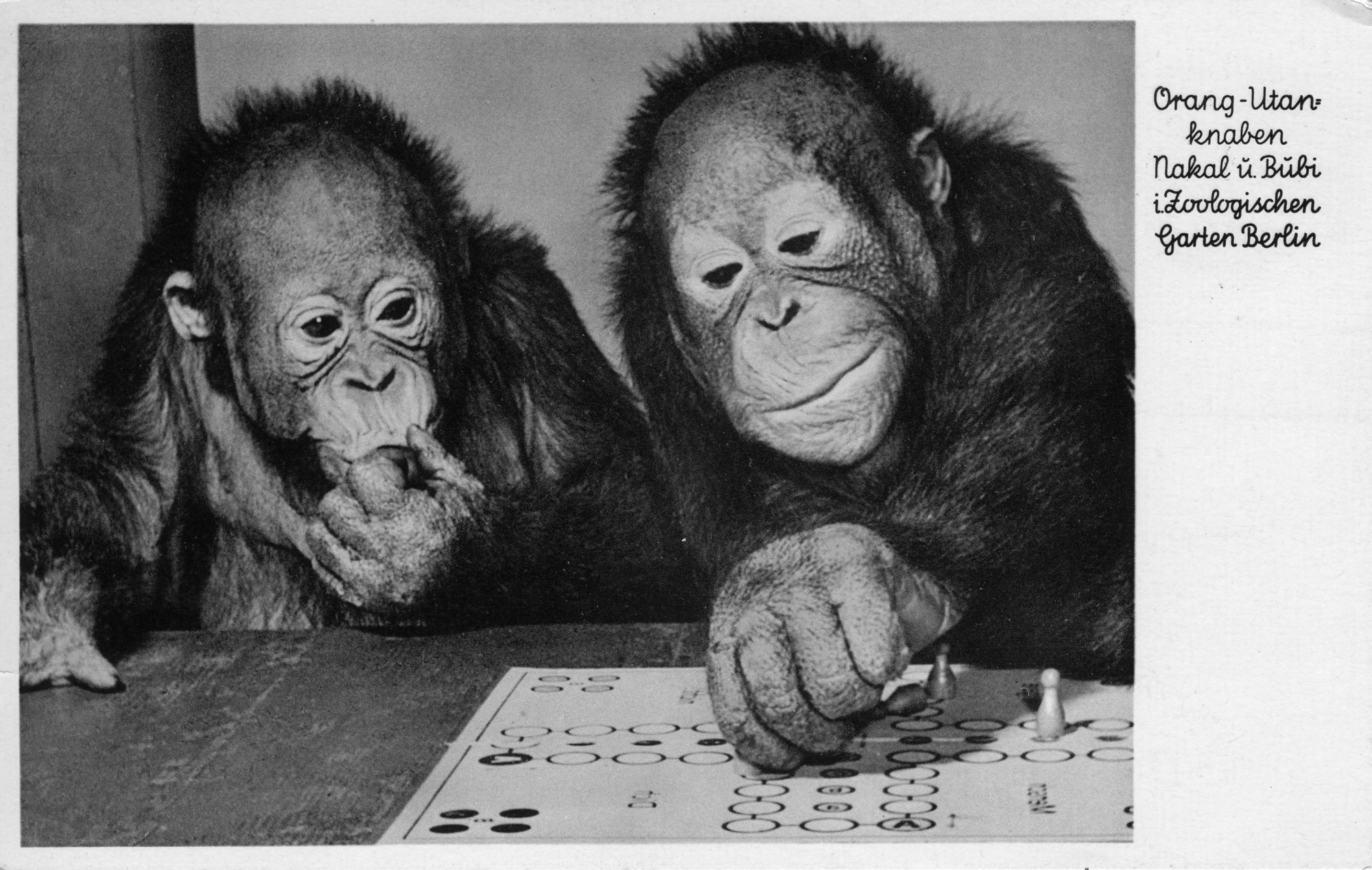

Of the animals that Katharina Heinroth brought back from this trip, for the public, the two male orangutan cubs “Bubi” and “Nakal” were undoubtedly the highlight. No one knows how Katharina Heinroth’s contacts got hold of these young animals, which were already accustomed to human interaction. In the zoo itself, the keepers maintained close contact with the orangutans, as was customary at the time. Photographs of humanising poses, such as this one with a game of Ludo, were among Berlin Zoo’s bestselling postcards.

Berlin Zoo postcard picturing the two orangutans “Bubi” und “Nakal”, 1959.

In 1963, Heinroth’s successor Heinz-Georg Klös went to Apartheid South Africa to catch a pair of southern white rhinos and bring them to the Berlin Zoological Garden. He had received the trapping permit from the South African authorities after a previous application had been rejected in 1957. Leineweber, a clothing store, paid for the two rhinos as part of an advertising campaign.24

White rhinos “Hlambamans” and “Kuababa” at Berlin Zoo, 1964. (AZGB, image: Kleinschmidt. All rights reserved.)

East Berlin’s newly opened zoo (known as the Tierpark) could rarely afford the animals that were caught in the wild and sold by trading houses. The enormous new zoo struggled due to a lack of foreign currency and general paucity of resources. Although there had been gifts from well-wishing zoos in the GDR, as well as the Federal Republic, they had hardly any of the animals that were most popular among the public. Nevertheless, the director of the Tierpark, Heinrich Dathe, did not miss out completely.

In July 1956, Vietnamese head of state Hồ Chí Minh received a delegation of the Solidarity Committee of the GDR for Korea and Vietnam, and of the National Council of the National Front, in Hanoi. It was mandatory at the time for the approved, so-called block parties of the GDR to come together with the SED under the banner of this latter organisation. Vietnamese animals were to be given to the delegation as a state gift, however the shipment was not yet ready by the time the delegation left the country. The Vietnamese authorities had had bears, pythons, monkeys, and even a tiger caught, and these animals now awaited departure in the port of Hanoi.

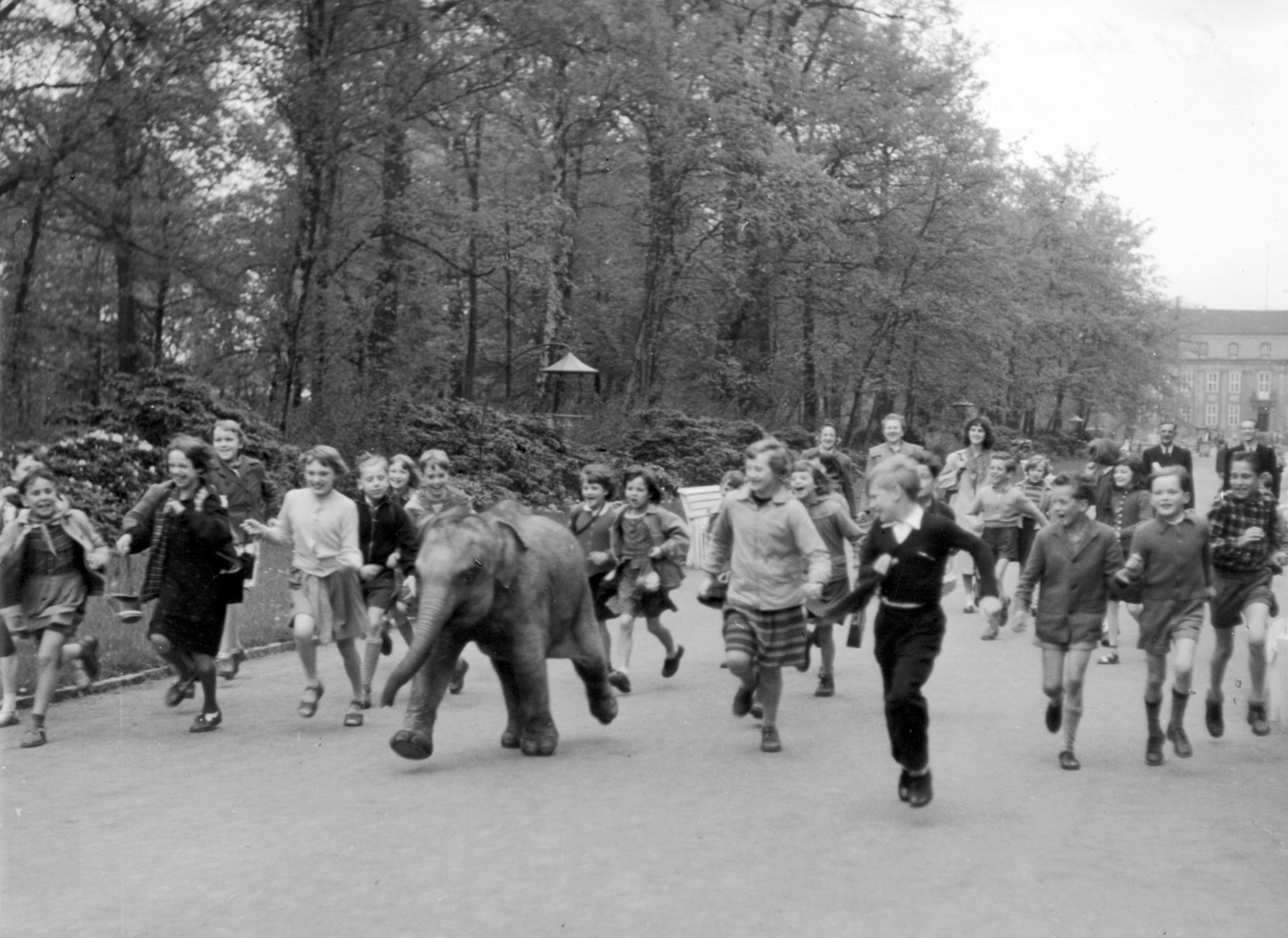

What came next was a debacle that went on for over a year. The newly created GDR could not source a ship of its own capable of calling at the port in good time. Some of the animals died in Hanoi. The city committee of the Patriotic Front in Hanoi had even procured an elephant, but the animal did not survive the winter of 1956/57. The Vietnamese attempted to capture another, but also requested for the deer and monkeys that were already ready for departure to be transported beforehand. The arrival of suitable transportation was repeatedly announced – and repeatedly cancelled. The list of animals awaiting shipment reported by the GDR Embassy in Hanoi changed constantly. When finally, a Polish ship transported the animals to the GDR, at least one elephant, a number of big cats and monkeys, as well as some ungulates had passed away.25 Nevertheless, the animal shipment provided excellent publicity for the zoo, and its success was certainly partly thanks to the elephant calf “Kosko”.

“Kosko” races with elated children, 1958. (Tierpark Berlin, image: Zimmer. All rights reserved.)

Today this success is regarded as having come at a high price: the death of the other animals during the long waiting period.

Better Husbandry Conditions, Breeding Successes, and the End of Commercial Animal Trapping

Around that time, there were signs that the trade in animals might be coming to an end. At the meetings of the International Union of Zoo Directors (today: WAZA) in 1958 and 1959, incumbent directors had already pointed to the problem of species extinction. Zoo director Heinrich Dathe reported on the panda and silver pheasant, and in the early 1960s, Bernhard Grzimek campaigned for an import ban on orangutans. In addition, veterinary medicine, especially reproductive medicine, and behavioral biology were advancing and those charged with the care of zoo animals were learning from these developments. Antibiotics and cardiovascular medication began to be used, and the life expectancy of animals in human care increased, not least due to a better understanding of  nutritional requirements, and larger enclosures. In 1983, it was still said of the Philadelphia Zoo:

nutritional requirements, and larger enclosures. In 1983, it was still said of the Philadelphia Zoo:

“Although one might assume that our nutritional knowledge of captive animals is complete because of our long history of captive animal efforts, 60 to 70% of the animals dying in captivity die because of poor management and husbandry, with nearly 25% dying from nutritional problems.”26

Overall, however, not only did zoo animals live longer, but they now also successfully reproduced more frequently. What was known as ‘Badezimmerarchitektur’ – relatively spartan ‘bathroom architecture’ – was introduced: an unsuitable form of zoo architecture by today’s standards, but innovative at the time. Tiled indoor stalls were easy to clean and thus reduced the threat posed by unwanted bacteria. In the 1960s, there was little awareness of the fact that, while this improved the animals’ longevity, it did little for their well-being. Glass panels, which became widespread from the late 1970s onward, constituted another architectural improvement in housing conditions. They prevented, for example, the transfer of germs to apes by human visitors and animals being fed unsuitable food. Read more on this in  Feeding and Overfeeding and

Feeding and Overfeeding and  Feeding Prohibited.

Feeding Prohibited.

The predator enclosure at Berlin Zoo was just one example of ‘bathroom architecture’, 1973. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

From the 1960s onward, zoos increasingly replaced animals caught in the wild with offspring bred in the zoos themselves, and those acquired through inter-zoo exchanges – for more on this, see  How Do Animals End Up in the Zoo?. Nowadays, species conservation efforts mean that zoos generally do not remove endangered species from the wild.

How Do Animals End Up in the Zoo?. Nowadays, species conservation efforts mean that zoos generally do not remove endangered species from the wild.

In 1973, a Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), also called the Washington Agreement, entered into force. To a great extent, the Convention ultimately put an end to the capture of endangered animals in the wild for zoos. Commercial trade in animals deemed endangered by the NGO the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and caught in the wild is prohibited. Trade in captive-bred offspring and non-commercial trade are possible, provided there is no threat to the continued existence of the species and national laws are observed. Many of the animals most popular with zoo visitors are already protected species.27 Others are subject to strict regulations. In addition, there are veterinary regulations to prevent epidemics and diseases. Zoos have little incentive to seek out mammals caught in the wild. Only aquariums continue to obtain specimens from the oceans, with the exception of many reptile species.

- Board minutes, 28.08.1845, AZGB O 0/1/76.↩

- Minutes of the General Assembly, 01.06.1852, AZGB O 0/1/62.↩

- Valuable insights into the history of the animal trade can be found in Lothar Dittrich. “Vom Souvenir zum Handelsobjekt: Handel und Import fremdländischer Tiere”. In Menagerie des Kaisers – Zoo der Wiener: 250 Jahre Tiergarten Schönbrunn, Mitchell G. Ash and Lothar Dittrich (eds.). Vienna: Pichler, 2002: 331-343; Lothar Dittrich. “Der Import von Wildtieren nach Europa: Einfuhren von der frühen Neuzeit bis zur Mitte des 20. Jahrhunderts”. In Tiere unterwegs: Historisches und Aktuelles über Tiererwerb und Tiertransporte, Helmut Pechlaner, Dagmar Schratter, and Gerhard Heindl (eds.). Vienna: Braumüller, 2007: 1-64.↩

- Dittrich, 2002: 332.↩

- Ludwig Heck. Heiter-ernste Lebensbeichte: Erinnerungen eines alten Tiergärtners. Berlin: Deutscher Verlag, 1938: 123ff.↩

-

Zoo ‘Inventory’

for 1897, Zoological Garden Berlin.

↩

Zoo ‘Inventory’

for 1897, Zoological Garden Berlin.

↩

- Cf. Oumar Diallo and Joachim Zeller. “Zoologischer Garten, Hardenbergplatz 8”. In Berlin – Eine (post-)koloniale Metropole: Ein historisch-kritischer Stadtrundgang im Bezirk Mitte, Farafina e.V. Berlin-Moabit (ed.). Berlin: Metropol-Verlag, 2021: 168-175. This is also shown by a systematic review of the annual reports between 1890 and 1914.↩

- Cf. for instance Bernhard Gissibl. The Nature of German Imperialism: Conservation and the Politics of Wildlife in Colonial East Africa. New York: Berghahn Books, 2016; Lara Domínguez and Colin Luoma. “Decolonising Conservation Policy: How Colonial Land and Conservation Ideologies Persist and Perpetuate Indigenous Injustices at the Expense of the Environment”. Land 9, no. 3 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/land9030065; David Prendergast. “Colonial Wildlife Conservation and the Origins of the Society for the Preservation of the Wild Fauna of the Empire (1903-1914)”. Oryx 37 (01.04.2003): 251-260. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605303000425; MacKenzie, John M. The Empire of Nature: Hunting, Conservation, and British Imperialism. Manchester: St. Martin’s Press, 1997; Angela Thompsell. Hunting Africa: British Sport, African Knowledge and the Nature of Empire. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.↩

- Carl Georg Schillings. Mit Blitzlicht und Büchse. Leipzig, 1905: 188.↩

- Ibid.: 190-197.↩

- Annual reports of the stock association of the Zoological Garden of Berlin for 1904 and 1908.↩

- Elizabeth Hanson. Animal Attractions: Nature on Display in American Zoos. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press, 2002: 71, 73.↩

- Eric Ames. Carl Hagenbeck’s Empire of Entertainments. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008: 28-29.↩

- Mareike Vennen. “Arbeitsbilder – Bilderarbeit: Die Herstellung und Zirkulation von Fotografien der Tendaguru-Expedition”. In Dinosaurierfragmente: Zur Geschichte der Tendaguru-Expedition und ihrer Objekte, 1906-2018, Ina Heumann, Holger Stoecker, Marco Tamborini, and Mareike Vennen (eds.). Göttingen: Wallstein, 2018: 56-75, (especially 64).↩

- Paul Eipper. Freund aller Tiere: Ein Fahrtenbuch voll bunter Abenteuer. Berlin: Ullstein, 1937: 94-95.↩

- Ames, 2008: 27.↩

- Ken Kawata. “Zoo Animal Feeding: A Natural History Viewpoint”. In Der Zoologische Garten 78, no. 1 (2008): 17-42.↩

- Examples in Hanson, 2002: 100-129. Besides contemporary newspaper articles, cf. also William M. Mann. “Wild Animals in and out of the Zoo”. Smithsonian Institution Series, vol. 6. New York: Smithsonian Institution, 1938; Kathleen Weidner Zoehfeld. Wild Lives: A History of the People & Animals of the Bronx Zoo. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006; and David Attenborough. Zoo Quest to Guiana. London: Lutterworth Press, 1956.↩

- Examples in Lutz Heck. “Auf Giraffenfang in Ostafrika”. Die Koralle 4, no. 10 (1928): 456-460; Lutz Heck. “Als Tierfänger in Ostafrika: Die Tierfangexpedition des Zoologischen Gartens in Berlin”. Die Koralle 5, no. 2 (1929): 82-86; Lutz Heck. “Als Tierfänger in Ostarfrika”. Die Kunst und ihre Welt, Januar (1930): 8-11; Lutz Heck. Aus der Wildnis in den Zoo: Auf Tierfang in Ostafrika. Berlin: Ullstein, 1930; Lutz Heck. “Über Giraffen und Giraffenfang”. Atlantis: Länder, Völker, Reisen 3, no. 8 (1931): 458-466; Lutz Heck. “Pavian-Fang in Abessinien”. Das Tier und wir, no. 6 (1934): 1-6; Lutz Heck. Auf Tiersuche in weiter Welt. Berlin: Paul Parey, 1941.↩

- Lothar Dittrich. “Der Import von Wildtieren nach Europa: Einfuhren von der frühen Neuzeit bis zur Mitte des 20. Jahrhunderts”. In Tiere unterwegs: Historisches und Aktuelles über Tiererwerb und Tiertransporte, Helmut Pechlaner, Dagmar Schratter, and Gerhard Heindl (eds.). Vienna: Braumüller, 2007.↩

- Bernhard Blaszkiewitz. “Beiträge zur Menschenaffenhaltung im Zoo Berlin nach 1945; 3. Mitteilung: Gorillas (Gorilla gorilla)”. Der Zoologische Garten 79, no. 6 (2010): 232-242.↩

- For information on breeding and catches, see “Zootierliste”. https://www.zootierliste.de/?klasse=1&ordnung=108&familie=10819&art=1071208 (02.06.2021).↩

- Katharina Heinroth. Mit Faltern begann’s: Mein Leben mit Tieren in Breslau, München und Berlin. Munich: Kindler, 1979: 203-212.↩

- Heinz-Georg Klös. Freundschaft mit Tieren: Der Altdirektor des Zoologischen Gartens Berlin erzählt. Berlin: Edition Q, 1997: 167-178.↩

- Copy GDR Ministry for Foreign Affairs to Solidarity Committee for Korea and Vietnam, 12.10.1956, Embassy of the GDR in Hanoi: Memo, 19.03.1957, PA AA, M 01/A 8367 and the entire correspondence on the matter with the Ministry in: Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amtes, the political archive of the Federal Foreign Office (PA AA), M 01/A 8367.↩

- C.T. Robbins. Wildlife Feeding and Nutrition. New York: 1983, cited from Kawata, 2008: 23.↩

- “Appendices”. CITES, https://cites.org/eng/app/appendices.php (02.06.2021).↩