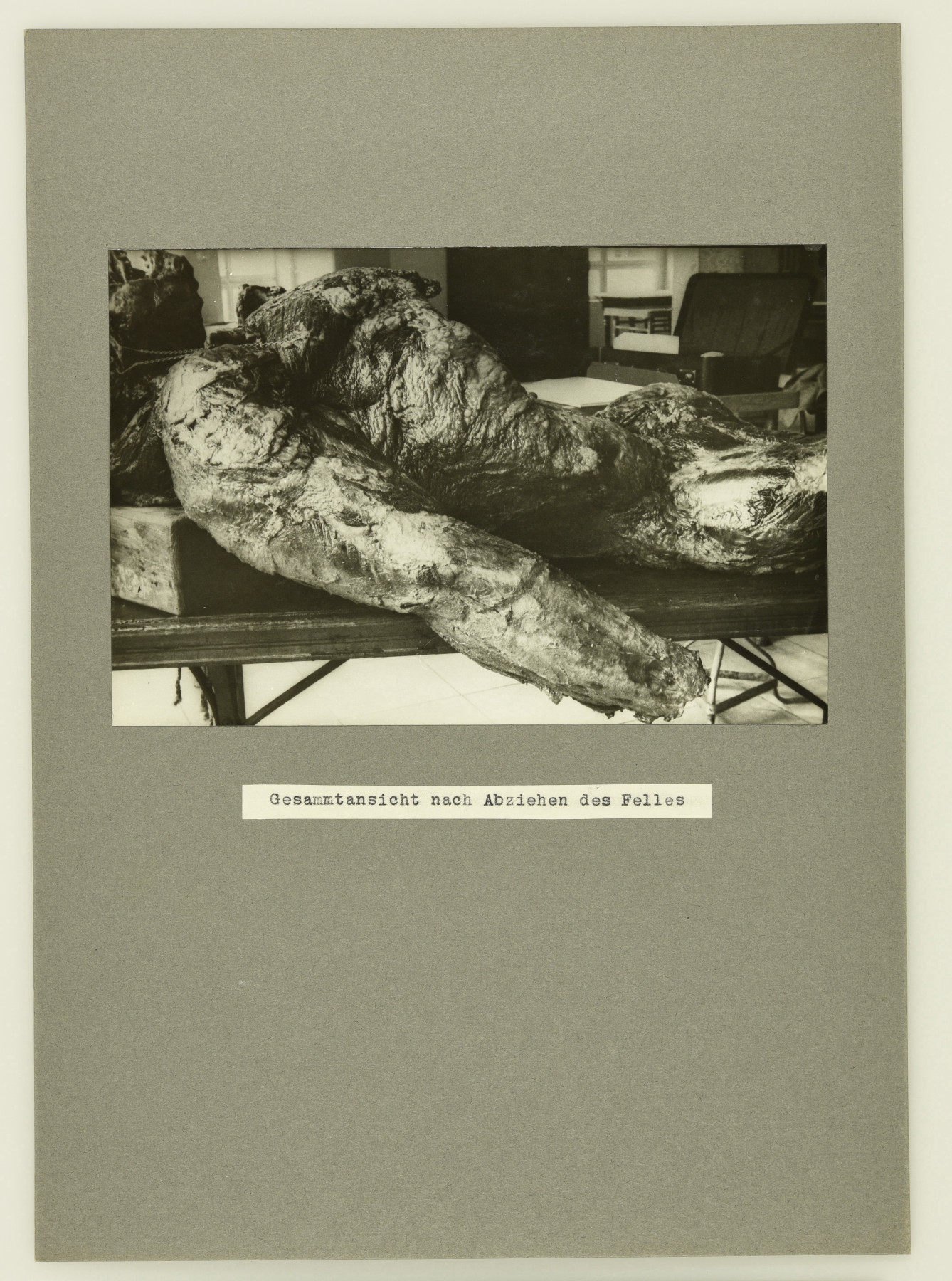

A photo of “Bobby” the gorilla’s carcass during his necropsy in 1935. (MfN, Historische Bild- und Schriftgutsammlungen [HBSB], ZM-B-IV-557-2-r. Image: W. Tank/MfN. All rights reserved.)

A carcass with its fur and hands removed, laid out on a stretcher. In this drastic photograph the animal appears as a dead, maimed object. In this image, some of the central questions we explore on this website crystallise: What are the processes that turn animals into objects – into objects of research, of collection, and exhibition? This photo was taken on 2 August 1935 during “Bobby’s” necropsy at the Pathological Institute of the Westend Hospital (Pathologischen Institut des Krankenhauses Westend) in Berlin-Charlottenburg.1 It documents one of the steps through which a dead body is transformed into an object of science: dissection – go  here for a perspective that challenges of the concept of ‘object’ further. That images of this event were taken at all was because the animal was special: “Bobby”, who lived in the zoo from 1928 to 1935, was not just an audience magnet, he was also Berlin Zoo’s first gorilla and the first gorilla to reach maturity in captivity.

here for a perspective that challenges of the concept of ‘object’ further. That images of this event were taken at all was because the animal was special: “Bobby”, who lived in the zoo from 1928 to 1935, was not just an audience magnet, he was also Berlin Zoo’s first gorilla and the first gorilla to reach maturity in captivity.

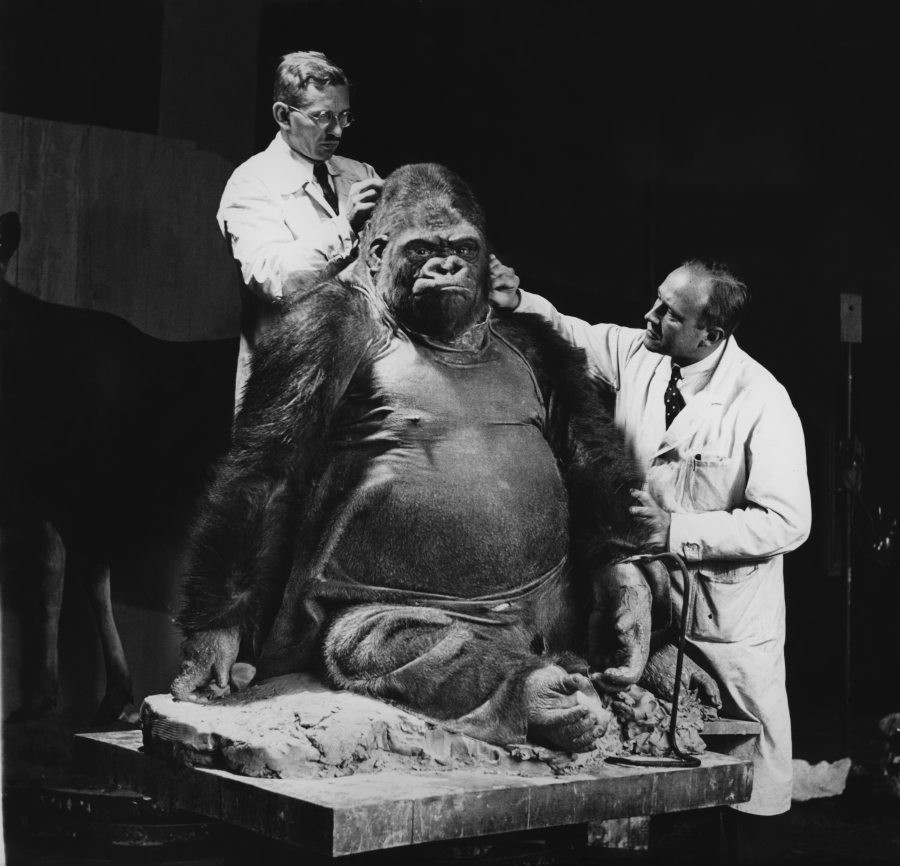

The skin, which has already been removed in the dissection photo, was used to prepare a taxidermy. In this photograph, the taxidermists Karl Kaestner and Gerhard Schröder are stitching it down at the Natural History Museum in Berlin. (MfN, HBSB, ZM-B-III-1232. All rights reserved.)

While “Bobby’s” taxidermy remains a popular display in the  exhibition at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin and both image and film material of the taxidermy process circulated,2 we know very little about “Bobby’s” dissection, despite this extensive documentation. We know just as little about how his body parts were subsequently distributed across various collections and institutions.

exhibition at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin and both image and film material of the taxidermy process circulated,2 we know very little about “Bobby’s” dissection, despite this extensive documentation. We know just as little about how his body parts were subsequently distributed across various collections and institutions.

This text attempts to reconstruct a largely unknown part of this famous zoo animal’s history through archive holdings and collection items. The starting point for this investigation was the discovery of the dissection records and other documents from the 1930s in the archive of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin. From there, clues led to various collections where specimens and replicas of the gorilla’s body parts remain to this day. The text represents an – at this stage still incomplete – historical reconstruction that connects different places and disciplines as it calls up larger and partly highly sensitive institutional, scientific, and collecting contexts. To fully investigate individual connections and the implications of recovering body parts remain important concerns for future research. What is clear, however, is that the history of “Bobby’s” scientific appropriation is different to the history of his  exhibition and

exhibition and  his popular reception.

his popular reception.

The dead gorilla “Bobby” at Berlin Zoo with his keeper Karl Liebetreu. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

“Bobby” died on 1 August 1935. This photo shows the gorilla shortly after his death at the zoo with his keeper Karl Liebetreu. From there, the animal was first taken to be dissected.3 This was not unusual. Most zoo mammals were dissected to determine their cause of death. However, the gorilla’s fame and the scientific interest he evoked in relation to pathological, biological and anatomical questions meant that the necropsy did not take place at the  Veterinary University (Tierärztliche Hochschule) but at the Pathological Institute of the Westend Hospital,4 usually reserved for studies of the human body. And it wasn’t just representatives from one but scientists (exclusively men) from a range of disciplines that took part in this dissection, which was, on top of everything, extensively documented.

Veterinary University (Tierärztliche Hochschule) but at the Pathological Institute of the Westend Hospital,4 usually reserved for studies of the human body. And it wasn’t just representatives from one but scientists (exclusively men) from a range of disciplines that took part in this dissection, which was, on top of everything, extensively documented.

“Bobby’s” necropsy first and foremost determined his cause of death: He died of a severe appendicitis.5 After the animal had been photographed, filmed, and measured, the necroscopy was carried out by Dr. Kleinschmidt and Dr. Groth from the Anatomical Institute at Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Berlin and the retired Geheimrat (privy councillor) Professor Hans Virchow.6 Also taking part was Professor W. Tank, anatomist at the Art Academy,7 who shot the black-and-white photographs that are now housed in the archive of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin. Each scientist was in charge of examining different body parts. Also present were collection staff and taxidermists from the museum. The necropsy lasted a total of seven days, from 2 to 8 August 1935. According to Friedrich Voss, head of the mammals department at the Natural History Museum at the time, the objective was to “scientifically analyse every inch of the animal if possible, right down to the last muscle fibre”.8 This included, firstly, publishing the results of the necropsy, which appeared in the Veröffentlichungen aus der Konstitutions- und Wehrpathologie (Publications from Constitutional and Defensive Pathology) in 1937. In addition, casts and taxidermies of various body parts were made. Their history leads from the Pathological Institute of the Westend Hospital to other sites inside and outside of Berlin, to the Museum für Naturkunde, the Berlin Zoo, Charité University Hospital, and – possibly – to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Brain Research (Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für Hirnforschung), see also  The Afterlife of Zoo Animals.

The Afterlife of Zoo Animals.

Dissection, Reproduction, Distribution

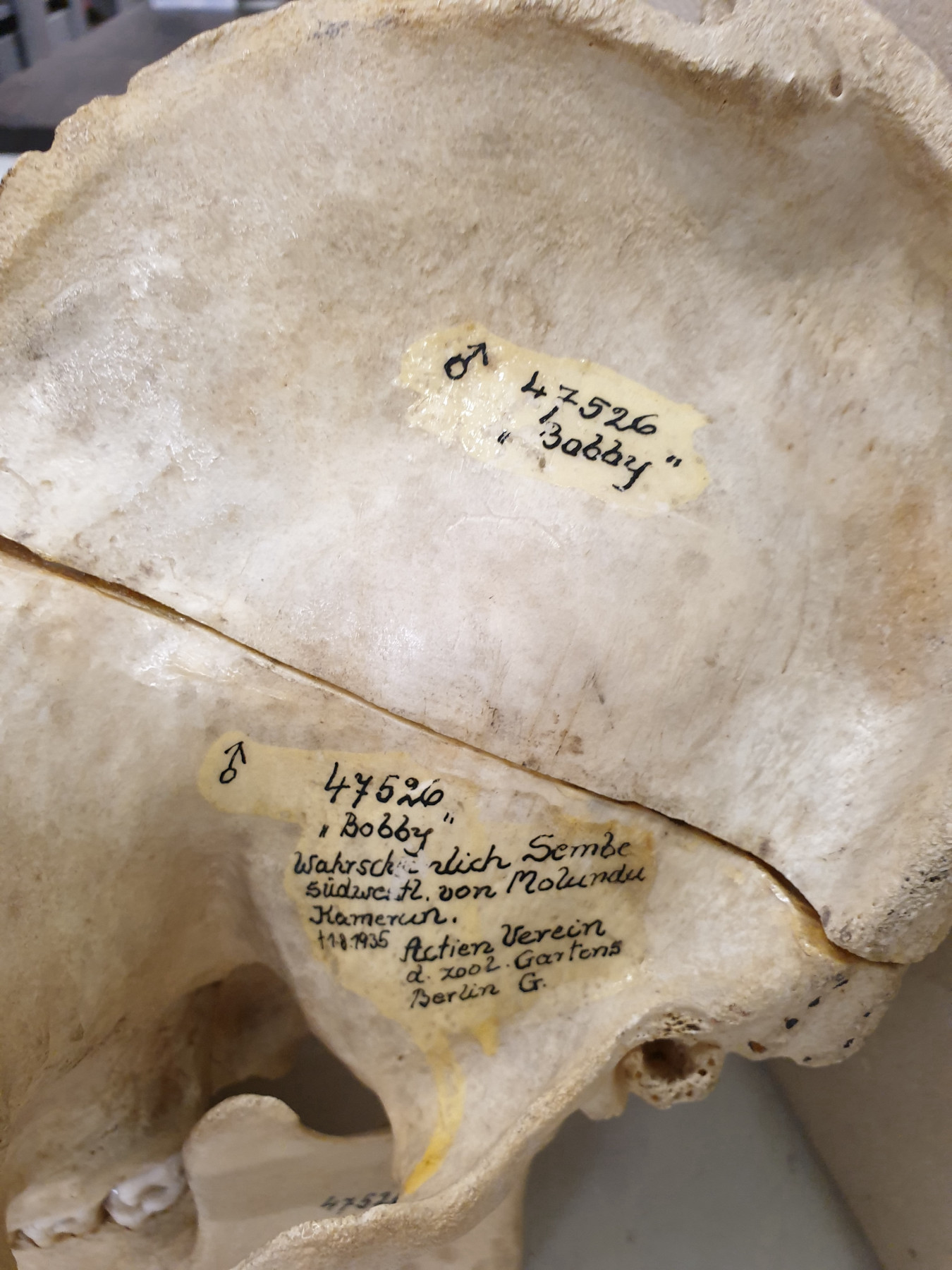

“Bobby’s” skull and various bones are being kept in the Mammals Collection at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin. (Images: Mareike Vennen/MfN. All rights reserved.)

The Natural History Museum in Berlin was the main recipient of the animal’s body parts, which it used for various purposes. While the gorilla’s skin was utilised for the taxidermy in the exhibition, his skull was transferred to the museum’s Mammals Collection, where it remains to this day. It becomes immediately apparent that this is a scientific object by, for example, looking at the bones, which were sawn through multiple times during the necropsy.9 Moreover, like many collection items, information about the animal’s provenance has been inscribed  on its skull: the likely origin ‘Probably Sembe southwest of Molundu Cameroon’ and the donor ‘Actien Verein d. Zool. Gartens Berlin G.’. The gorilla has been transformed from a

on its skull: the likely origin ‘Probably Sembe southwest of Molundu Cameroon’ and the donor ‘Actien Verein d. Zool. Gartens Berlin G.’. The gorilla has been transformed from a  wild animal into a

wild animal into a  zoo animal and, ultimately, into a collection item. Further up on the skull, the

zoo animal and, ultimately, into a collection item. Further up on the skull, the  inventory number ‘ZMB 47528’ has been noted, identifying the skull as a collection item. Below we can see his

inventory number ‘ZMB 47528’ has been noted, identifying the skull as a collection item. Below we can see his  popular name, ‘Bobby’. This juxtaposition between scientific and popular language illustrates not just the animal’s

popular name, ‘Bobby’. This juxtaposition between scientific and popular language illustrates not just the animal’s  celebrity but also the tension between anthropomorphisation and scientific objectification.

celebrity but also the tension between anthropomorphisation and scientific objectification.

We can also find traces of “Bobby” in the museum’s wet collection. Wet specimens have been preserved in seven jars, among them his right foot. The left foot and his two hands are missing. I have not been able to find their whereabouts yet.

Further clues take us outside the museum. According to the necropsy report, the animal’s brain was transferred to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Brain Research for scientific research.10 The archive of the Max Planck Society (since 1948 the name of the former Kaiser Wilhelm Society) has not been able to identify any sources in its holdings that prove that “Bobby’s” brain was in fact sent to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute or examined there. There could be several reasons for this: either the gorilla’s brain was not transferred there after all, or it was not received, or the documentation is no longer available to us – the holdings of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Brain Research (I. Abt., Rep. 21) were almost completely destroyed during the Second World War. Thus, despite the missing sources, we cannot exclude the possibility that the brain was in fact transferred to the institute and examined there.11 In any case, the fact that the brain was supposed to be delivered there points to a historically specific context that is rather sensitive from a contemporary perspective, namely, to the history of the institute. The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics was, from 1927 to 1945, the most renowned research institution for human genetics in Germany. In dealing with subjects such as the origin and descent of man it scientifically legitimated the  National Socialist race policy and was later directly involved in National Socialist crimes.12 In its research activities between 1940 and 1945, the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Brain Research brutalised the brains of people who had been murdered in the context of the National Socialist’s eugenic programmes.13 We have not yet been able to determine whether the specimen of “Bobby’s” brain still exists or where it might be today.

National Socialist race policy and was later directly involved in National Socialist crimes.12 In its research activities between 1940 and 1945, the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Brain Research brutalised the brains of people who had been murdered in the context of the National Socialist’s eugenic programmes.13 We have not yet been able to determine whether the specimen of “Bobby’s” brain still exists or where it might be today.

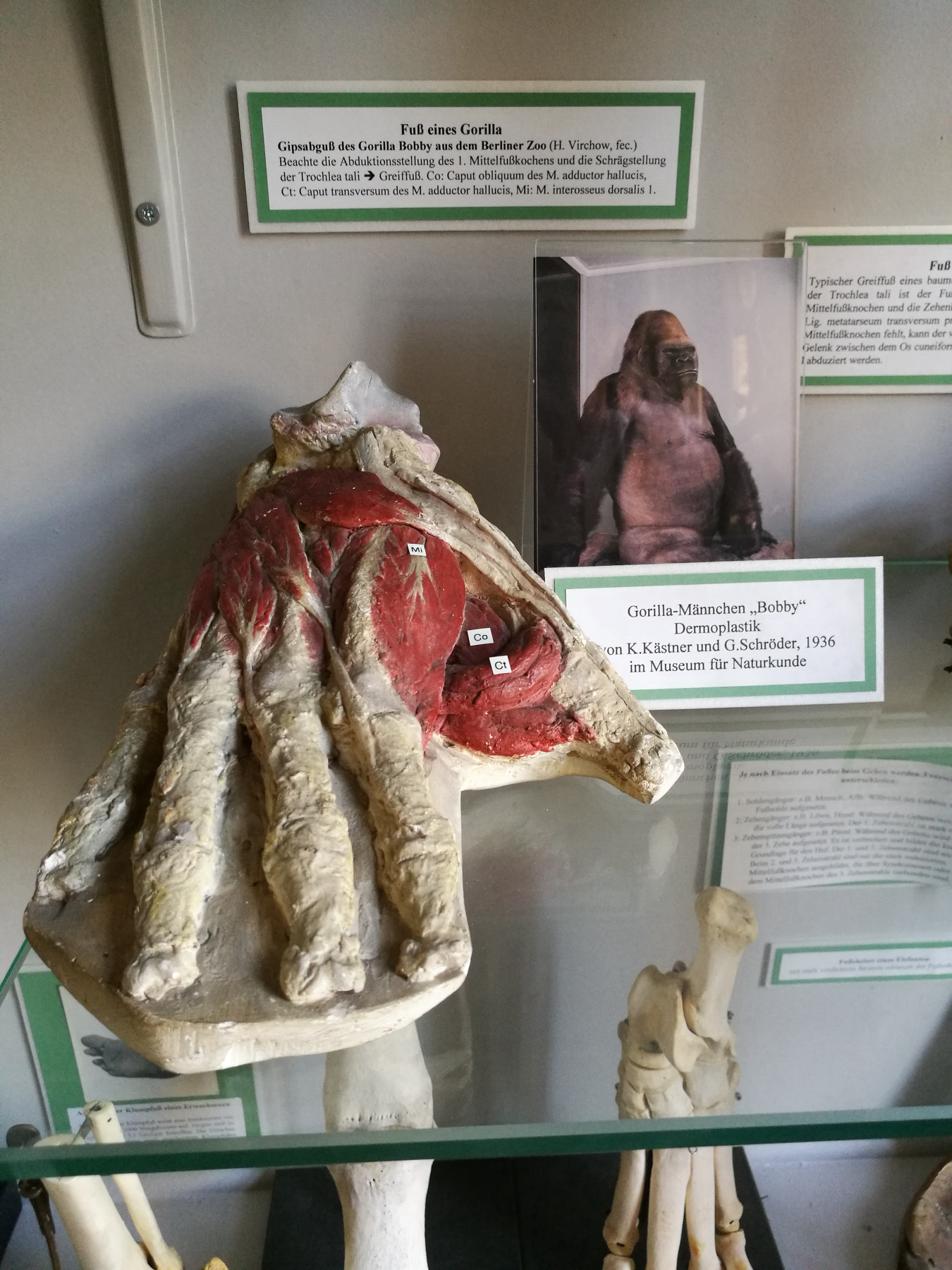

Before the individual body parts were prepared and donated to other institutions, a further scientific technology was deployed: reproduction by way of plaster casts. To begin with, the museum’s taxidermists made casts of “Bobby’s” various body parts to  prepare the taxidermy.14 This required the carcass to be completely cleaned of tissue the day after the anatomical examinations had concluded. Then a full cast of the skeleton was made for the

prepare the taxidermy.14 This required the carcass to be completely cleaned of tissue the day after the anatomical examinations had concluded. Then a full cast of the skeleton was made for the  the museum’s exhibition before all of the casts and bones were sent to the museum. Moreover, casts were made for collections that held both human and animal specimens. Hans Virchow made a plaster cast of the exposed musculature of “Bobby’s” palm and sole. He also prepared his hand and right foot after having produced casts of both. These casts are still on display in a case in the Anatomical Collection of the Charité University Hospital (Hans Virchow’s former workplace).15 The cast of the prepared foot, including partial labelling of the gorilla’s foot muscle, is displayed in the teaching collection in a vitrine together with feet of other animals.

the museum’s exhibition before all of the casts and bones were sent to the museum. Moreover, casts were made for collections that held both human and animal specimens. Hans Virchow made a plaster cast of the exposed musculature of “Bobby’s” palm and sole. He also prepared his hand and right foot after having produced casts of both. These casts are still on display in a case in the Anatomical Collection of the Charité University Hospital (Hans Virchow’s former workplace).15 The cast of the prepared foot, including partial labelling of the gorilla’s foot muscle, is displayed in the teaching collection in a vitrine together with feet of other animals.

The casts of “Bobby’s” hand and foot made by Hans Virchow are still housed in the Anatomical Teaching Collection on the premises of the Charité University Hospital. (Image of the two hand casts and the two foot casts: Evelyn Heuckendorf/Charité. All rights reserved. Image of gorilla and human hand and image of gorilla foot in display case: Mareike Vennen/Charité. All rights reserved.)

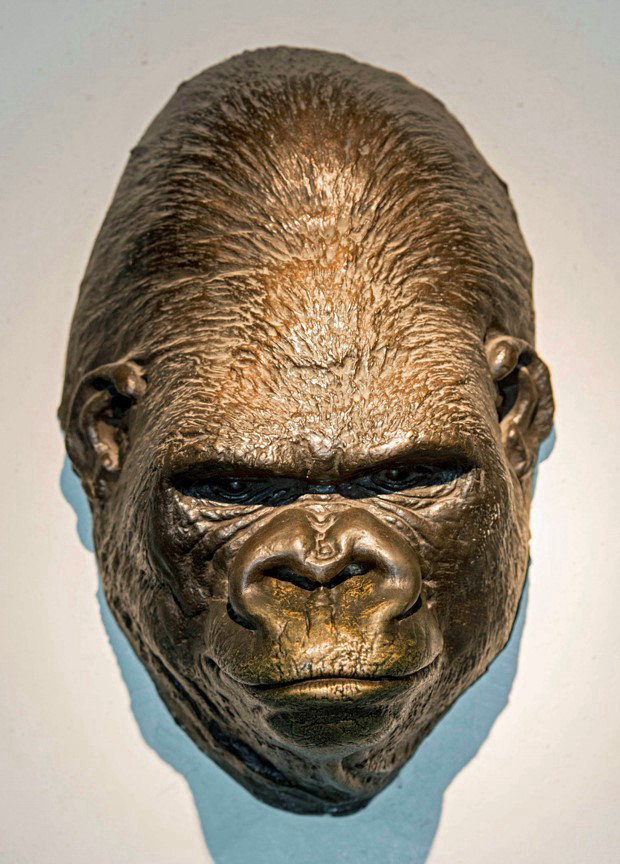

Finally, a plaster cast was made of “Bobby’s” face. Death masks like these were made of the faces of (famous) people as well as animals to preserve their characteristic features. They, too, were used to prepare the taxidermy but also served a  culture of remembrance. That the zoo had commissioned another cast of “Bobby’s” face made in bronze would suggest a more memorial function.16 Today, several death masks of “Bobby’s” face circulate: one of them is mounted in the Ape House, and we found another in the Berlin Zoo’s archive. There are also death masks of “Bobby” at the Museum für Naturkunde, for instance, in the preparators’ workshop. We assume that even more will be found.

culture of remembrance. That the zoo had commissioned another cast of “Bobby’s” face made in bronze would suggest a more memorial function.16 Today, several death masks of “Bobby’s” face circulate: one of them is mounted in the Ape House, and we found another in the Berlin Zoo’s archive. There are also death masks of “Bobby” at the Museum für Naturkunde, for instance, in the preparators’ workshop. We assume that even more will be found.

Bronze death mask of “Bobby” at Berlin Zoo and case with another death mask in the exhibition at the Natural History Museum in Berlin, probably in the 1960s. (Top image: AZGB. All rights reserved. Image below: MfN, HBSB, B-V-0727. All rights reserved.)

The well-documented case of “Bobby” thus allows us to understand not just how preparation technologies can be used to produce a  taxidermy and therefore transform the animal into a ‘lifelike’ exhibition object. It also illustrates the techniques – dissecting, measuring, documenting, preparing, and casting – that turn animals into scientific collection items and objects of scientific research and, not least, into objects of memory.

taxidermy and therefore transform the animal into a ‘lifelike’ exhibition object. It also illustrates the techniques – dissecting, measuring, documenting, preparing, and casting – that turn animals into scientific collection items and objects of scientific research and, not least, into objects of memory.

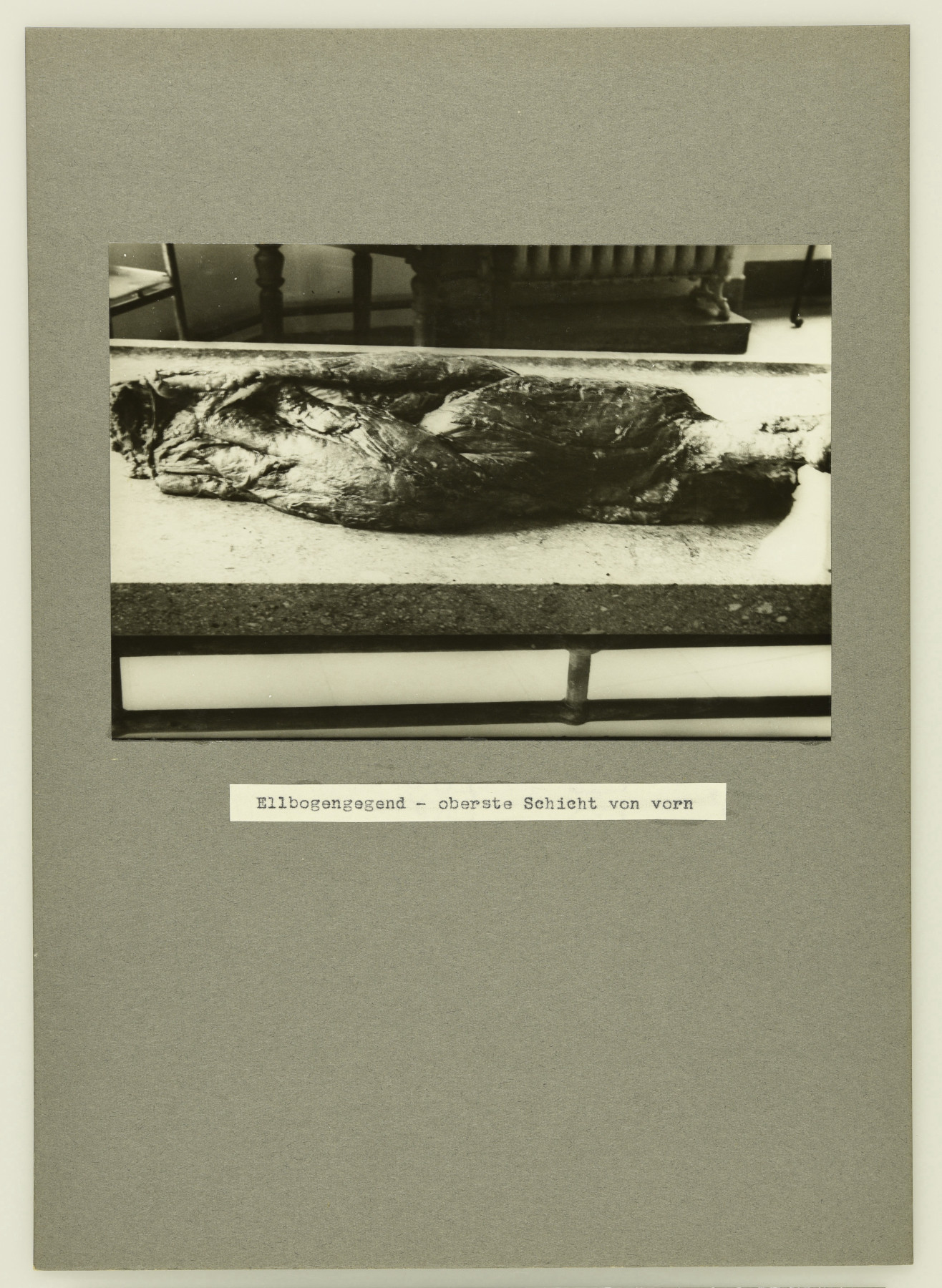

The necropsy report that documents the dissection and examination of the gorilla’s body continues the body’s dismemberment, not by means of a scalpel, but in word and image.17 The 24 large-format photos that capture the necropsy procedure in images are also part of a  documentation practice that understands and appropriates the animal as an object of knowledge.18They evidence the body’s cuts that precede its progression toward scientific appropriation und utilisation.

documentation practice that understands and appropriates the animal as an object of knowledge.18They evidence the body’s cuts that precede its progression toward scientific appropriation und utilisation.

This photograph with the caption “elbow top layer from the front” from the necropsy record forms one part of the scientific documentation practice. It presents the animal as a piece of meat and as an object of anatomical research. (MfN, HBSB, ZM-B-IV-557-18-r. All rights reserved.)

Setting out in search of “Bobby” today means setting out in search of  individual body parts, a quest that leads through different institutions. His life is thus not just a part of

individual body parts, a quest that leads through different institutions. His life is thus not just a part of  colonial history; rather, his life and afterlife are also part of the history of the city of Berlin. Tracing its

colonial history; rather, his life and afterlife are also part of the history of the city of Berlin. Tracing its  material culture points to a number of collections and research facilities across the city that dealt with animals and the – from today’s perspective sometimes problematic – knowledge about them. The scientific and collection history of “Bobby” is yet to be written. However, the collaboration of different disciplines during and after the necropsy shows that this animal has made its way into multiple research fields, including pathology, anatomy, and zoology.

material culture points to a number of collections and research facilities across the city that dealt with animals and the – from today’s perspective sometimes problematic – knowledge about them. The scientific and collection history of “Bobby” is yet to be written. However, the collaboration of different disciplines during and after the necropsy shows that this animal has made its way into multiple research fields, including pathology, anatomy, and zoology.

This text could only provide a cursory sketch of the use of techniques such as dissection, reproduction, and distribution. But these techniques raise many more questions, not least about their genealogy and the historical contexts in which they have been applied: To what extent do the dissection and  distribution of animal bodies or body parts continue colonial scientific practices as well as colonial trade in animals and their body parts? The distribution of objects to different collections and research facilities is congruent with a practice of collecting that was widespread in the 19th and early 20th centuries. This combined the collection of botanical, ethnographic, zoological, and other objects in the field before routing them into different collections and institutions. At the same time, as mentioned above, dissecting one and the same body and sending its individual body parts to different collections is a practice also applied to human beings. So-called ‘human zoos’ as part of zoos, industrial and world exhibitions not just exhibited people: during the first German Colonial Exhibition in 1896, held as part of the Berlin Industrial Exposition at Treptower Park, 106 people from German colonies like Cameroon and Togo were made to be part of such a ‘human zoo’. The ethnologist and anthropologist Felix von Luschan arranged for the body parts of any participants that might die to be examined at the Anatomical Institute at the university in Berlin. Their brains would remain in the collection, while their bones would be sent to Luschan’s collection at the ethnological museum in Berlin.19

distribution of animal bodies or body parts continue colonial scientific practices as well as colonial trade in animals and their body parts? The distribution of objects to different collections and research facilities is congruent with a practice of collecting that was widespread in the 19th and early 20th centuries. This combined the collection of botanical, ethnographic, zoological, and other objects in the field before routing them into different collections and institutions. At the same time, as mentioned above, dissecting one and the same body and sending its individual body parts to different collections is a practice also applied to human beings. So-called ‘human zoos’ as part of zoos, industrial and world exhibitions not just exhibited people: during the first German Colonial Exhibition in 1896, held as part of the Berlin Industrial Exposition at Treptower Park, 106 people from German colonies like Cameroon and Togo were made to be part of such a ‘human zoo’. The ethnologist and anthropologist Felix von Luschan arranged for the body parts of any participants that might die to be examined at the Anatomical Institute at the university in Berlin. Their brains would remain in the collection, while their bones would be sent to Luschan’s collection at the ethnological museum in Berlin.19

As the example of the Anatomical Collection at Charité shows, anatomical collections may also contain zoological specimens, probably for the purpose of comparison. What role did the Anatomical Institute at Westend and the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Brain Research play in “Bobby’s” case? Did their research forge links between science, animal bodies, and societal ideas about ‘race’? In turn, casting techniques raise questions not least about the relationship between uniqueness and reproduction and, therefore, about the issue of authenticity. Death masks – probably the most well-known form of face casts – do not just produce images of life, but also make reference to live casts. Although they were already being used in antiquity, impressions of the living body made in wax and plaster were used above all in the mid-19th century for anthropological and ethnographic purposes in order to document racist and racializing measures. Britta Lange has shown how colonial exhibitions that had been held in the German-speaking world since the 1890s usually presented a series of ‘Rasseköpfe’ (‘racial’ heads), wax casts of the inhabitants of colonised territories. These racialised heads could also be found in anatomical and natural history museums in the second half of the 19th century, where they replaced or supplemented preserved head specimens.20 What of these contexts was still apparent in 1930s Berlin? What can we still see today? With regard to animals, too, this raises questions about which parts were used for which purposes and at what cost. What is clear is that when dissection techniques turn one object into many, as in “Bobby’s” case, the contexts and potential crimes, too, are multiplied.

- According to the necropsy report, the ape, who died on the afternoon of 1 August 1935, had already been taken to the refrigeration room of the Pathological Institute of the Westend Hospital three hours after his death. The necropsy began the next day.↩

- The taxidermy of the animal was created by Berlin taxidermists Karl Kaestner (1895-1983) and Gerhard Schröder (1896-1945) in the same year. They used a new technique they developed. It involved partially replenishing sparsely haired body parts with paraffin wax. This allowed preservation of fine structures in face and hands and prevented shrinking during the drying process. The water contained in the cells is substituted by solid substances such as paraffin wax or polyethylene glycol. Information taken from: Museum für Naturkunde Berlin. https://www.museumfuernaturkunde.berlin/en/museum/exhibitions/masterpieces-taxidermy (17.12.2021).↩

- When his limbs were removed and where his hand might have gone remain unanswered questions.↩

- It was the first urban hospital of what would later be metropolitan Berlin for which an in-house pathological institute (now building 19) had been included in the plans.↩

- Cf. F. Voss to L. Heck, 28.1.1936, MfN, HBSB, S004‐02‐05 no. 97.↩

- Virchow had already retired in 1922. The fact that the 83-year-old was responsible for preparing the specimens of “Bobby’s” hand and foot indicates how famous both the animal and the scientist were.↩

- Each of them examined different body parts: Groth examined the neck musculature; Kleinschmidt worked on the neck and chest, and on the superficial back, pelvis, and arm muscles. Virchow examined “Bobby’s” back musculature, while Tank captured the individual sections in photos.↩

- F. Voss to L. Heck, 28.1.1936, MfN, HBSB, S004‐02‐05 no. 97.↩

- MfN, HBSB, S004-02-05 134, Pohle estate.↩

- Walter Koch. “Bericht über das Ergebnis der Obduktion des Gorilla Bobby des Zoologischen Gartens zu Berlin”. Veröffentlichung aus der Konstitutions- und Wehrpathologie 40, no. 9,3 (1937): 1-36, 7.↩

- I would like to thank Simon Nobis from the Max Planck Society Archive for his support.↩

- The founding director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Eugen Fischer, wanted his approach, which he termed ‘anthropobiology’, to find genetic principles for the ‘phenotypical’ diversity of humans, i.e., for differences in skin, hair, and eye colour; and to connect anthropometric methods, i.e., the measuring of human bodies and skeletons, with questions and methods of ‘heredity’, that is, of human genetics. On Eugen Fischer and the institute’s problematic history, see Carola Sachse and Benoit Massin. Biowissenschaftliche Forschung an Kaiser-Wilhelm-Instituten und die Verbrechen des NS-Regimes: Informationen über den gegenwärtigen Wissensstand. Berlin: Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, 2000; Hans Walter Schmuhl. Grenzüberschreitungen: Das Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für Anthropologie, menschliche Erblehre und Eugenik, 1927-1945. Göttingen: Wallstein, 2005. The Natural History Museum in Berlin received a replica of the brain (which we have not yet been able to locate).↩

- Cf. H.-W. Schmuhl. “Hirnforschung und Krankenmord: Das Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für Hirnforschung 1937-1945”. In Forschungsprogramm “Geschichte der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft im Nationalsozialismus”. Präsidentenkommission der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft (ed.), 2000, http://www.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/KWG/Ergebnisse/Ergebnisse1.pdf.↩

- They made casts of the uninjured left side, the left side of the chest after the large chest muscle had been removed, and more casts of the pelvic musculature.↩

- This is the Anatomical Collection of the Specialty Network Anatomy at the Charité University Hospital in Berlin, parts of which are open to the public. The specimen and demonstration collection comprises objects such as anatomical specimens; wax, plaster, and wooden models; plastinates; and pathological anatomical, and zoological objects; as well as the death masks of significant personalities. I would like to thank Evelyn Heuckendorf for providing me with access to the collection and for her tips, which have been incorporated into this text.↩

- L. Heck to F. Voss, 10.12.1935, MfN, HBSB, S004‐02‐05 no. 97.↩

- See Koch, 1937.↩

- The photographs are now housed in the archive of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin. Because body parts have to be prepared quickly (especially during the hot August of 1935), the photos were “only taken using the Leika, often in very unfavourable lighting conditions”. The photos were taken to document the procedure and were intended for internal use in order to illustrate the shapes and characteristics of specific body parts. The necropsy report also mentions film recordings, about which I have unfortunately not yet been able to find any information on.↩

- On the connection between human zoos and the racialisation of human bodies, see Susann Lewerenz. “Völkerschauen und die Konstituierung rassifizierter Körper”. In Marginalisierte Körper: Beiträge zur Soziologie und Geschichte des anderen Körpers Torsten Junge und Imke Schmincke (eds.). Münster: Unrast, 2007: 135-153. On the human zoos in Stellingen and Berlin, see Hilke Thode-Arora. Für fünfzig Pfennig um die Welt: Die Hagenbeckschen Völkerschauen. Frankfurt a.M.: Campus-Verlag, 1989; Clemens Maier-Wolthausen. Hauptstadt der Tiere. Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag, 2019. On human remains in German collections, see, e.g., Larissa Förster and Holger Stoecker. Haut, Haar und Knochen: Koloniale Spuren in naturkundlichen Sammlungen der Universität Jena. Weimar: Verlag und Datenbank für Geisteswissenschaften, 2016; Holger Stoecker et al. (eds.). Sammeln, Erforschen, Zurückgeben?: Menschliche Überreste aus der Kolonialzeit in akademischen und musealen Sammlungen. Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag, 2013.↩

- Britta Lange. Echt Unecht Lebensecht: Menschenbilder im Umlauf. Berlin: Kadmos, 2006: 243. Sophia Gräfe. “Totenmaske für einen Fuchs”. In Wissensdinge: Geschichten aus dem Naturkundemuseum, Anita Hermannstädter, Ina Heumann, and Kerstin Pannhorst (eds.), 2nd ed. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer 2020: 192-193.↩