A little boy with a lion cub on the Berlin Zoo photographer’s bench in 1939. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

Many are probably familiar with the photo motif: a man, woman, or child with a young lion on their lap. Sometimes they look either lovingly or fearfully at the animal, sometimes they look directly at the camera. In other photos, the subject of the photo looks outside the image, like in this photo, which was taken at the Berlin Zoo in 1939. Many zoos once gave visitors the opportunity to have their photos taken with a lion cub. When did this motif emerge, and why has it disappeared from today’s zoos? What do photos like these reveal about the  relationship between zoo visitors and lion cubs? What attitudes towards and ideas about ‘wild animals’ take shape in these images, and how did animals become photo objects in the first place? And finally: What is the animal here? Is it a predator, a zoo animal, or a stuffed toy? The quest for answers does not just take us through the history of photography practice and zookeeping, but also has a lot to do with the changing politics of animal images.

relationship between zoo visitors and lion cubs? What attitudes towards and ideas about ‘wild animals’ take shape in these images, and how did animals become photo objects in the first place? And finally: What is the animal here? Is it a predator, a zoo animal, or a stuffed toy? The quest for answers does not just take us through the history of photography practice and zookeeping, but also has a lot to do with the changing politics of animal images.

Contact Zones Between Animals and Humans

Getting within touching distance of young predators like bears, lions, or leopards – what now seems perplexing was very popular for a long time. The lion cub photo motif can be traced back to at least the 1930s,1 revealed if nothing else by the clothing the little boy is wearing and the sepia colouring of the photo from Berlin Zoo, which was taken in 1939. There were reports about visitors’ desiring to get as close as possible to the baby animals at the zoo. Lions seem to have had a particularly strong appeal. “The desire to take a lion in one’s arms and stroke it is probably one of the most coveted amongst our zoo visitors”, as Hamburg’s Stellingen Zoo reported in 1926.2 And some zoos did in fact provide this opportunity. The Berlin Zoological Garden had been organising its own ‘baby animal zoo’ every summer since 1931. In a fenced-in enclosure, visitors were able to cuddle, stroke, and feed not just sheep and goats but also little lion and tiger cubs. Other zoos followed suit with special shows and  petting zoos for baby predators.

petting zoos for baby predators.

A drawing in the Berliner Illustrirten Zeitung puts the role of the baby predator in a nutshell with the headline “A Live Animal Toy”.

Photographs of children holding lion cubs, which visitors could later have taken by the Berlin Zoo photographer, captured for a visitor’s photo album the moment in which they touched a juvenile predator. The mainly privately run photography booths had been popular since the  1930s and 1940s for various reasons: firstly, they provided an opportunity to immortalise a visit to the zoo in an individual or family portrait – at a time when photographic equipment were still much more expensive and much heavier than they are today. Moreover, the practice of taking private photos of zoo animals was nowhere near as widespread back then as it is today, especially considering that, in many zoos, such as those in Berlin, Vienna, Leipzig, and Halle, it was only possible to take photographs on zoo premises by paying for a permit.3 The photographer brought the animals close to the camera. What is more: photography booths provided a place where people and zoo animals could interact and come into direct contact with one another, and professional photos turned these moments into a “permanent memento of a visit to the zoo”, as the 1938 guide to Berlin Zoo advertised.4

But were these photos really about the animals? What role did the lion cubs play? Were they props in family portraits or exoticised extras? While each individual photo captured a specific memory, and even though photo quality, fashion, and hairstyles changed over the years, all of these images are very similar. This is mainly due to their setting, which barely changed in 70 years: a bench, a human or humans, and a lion cub.

1930s and 1940s for various reasons: firstly, they provided an opportunity to immortalise a visit to the zoo in an individual or family portrait – at a time when photographic equipment were still much more expensive and much heavier than they are today. Moreover, the practice of taking private photos of zoo animals was nowhere near as widespread back then as it is today, especially considering that, in many zoos, such as those in Berlin, Vienna, Leipzig, and Halle, it was only possible to take photographs on zoo premises by paying for a permit.3 The photographer brought the animals close to the camera. What is more: photography booths provided a place where people and zoo animals could interact and come into direct contact with one another, and professional photos turned these moments into a “permanent memento of a visit to the zoo”, as the 1938 guide to Berlin Zoo advertised.4

But were these photos really about the animals? What role did the lion cubs play? Were they props in family portraits or exoticised extras? While each individual photo captured a specific memory, and even though photo quality, fashion, and hairstyles changed over the years, all of these images are very similar. This is mainly due to their setting, which barely changed in 70 years: a bench, a human or humans, and a lion cub.

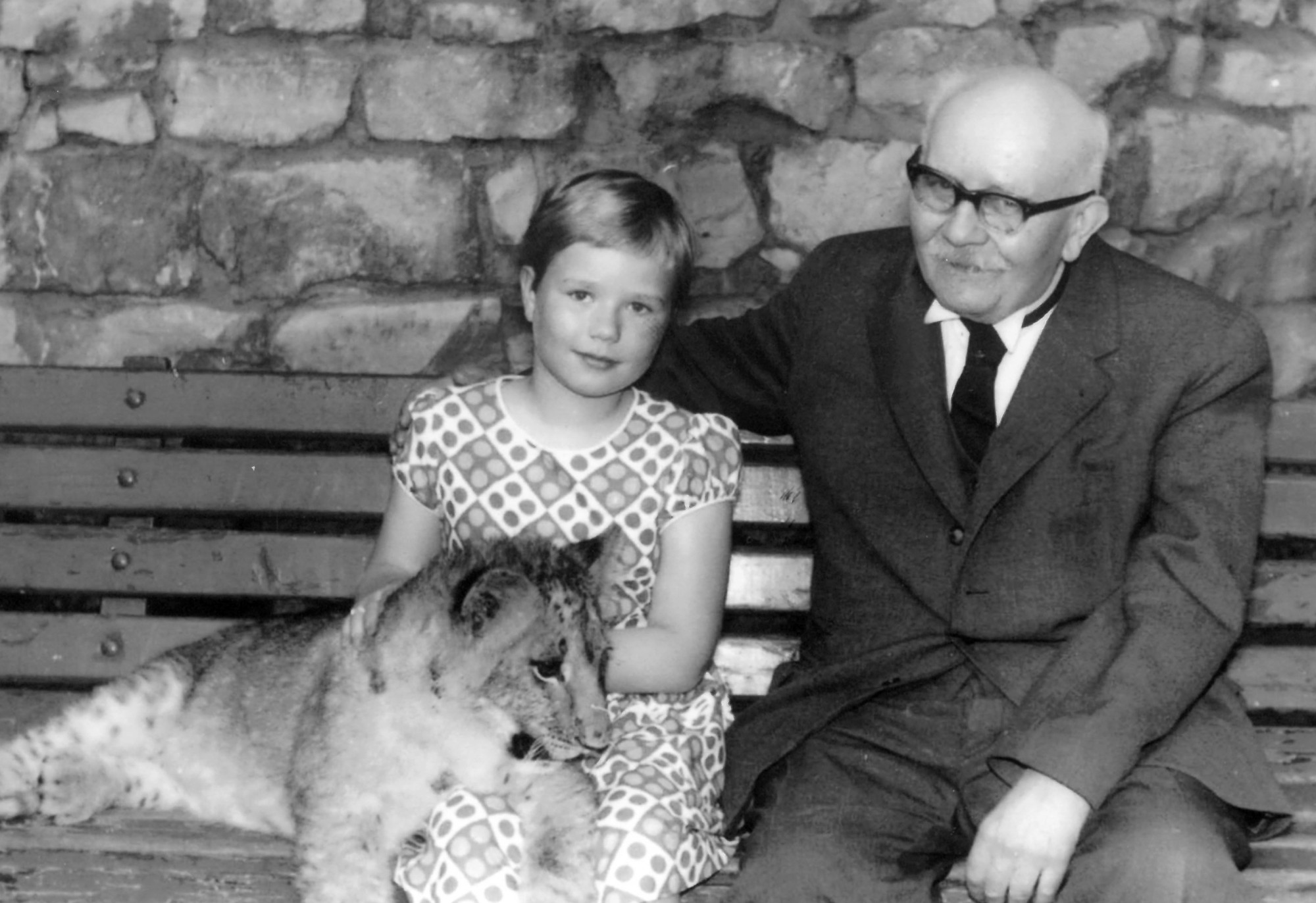

Family photo with a lion cub. Granddad and granddaughter look directly at the camera in 1962. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

This transforms photos of this genre from private memories into historical documents that go beyond individual histories. They show cultural phenomena, as the cultural studies scholar Christina Wessely writes. According to her book Löwenbaby (Lion Cub), this image genre does not just tell us about animals, but above all about humans, about family constellations, and about changing ideas of nature.5 At the same time, we might add, they also tell us about the relationship between the  media production of animal images and the reproduction of animals in

media production of animal images and the reproduction of animals in  breeding programmes.

breeding programmes.

From Animals Slain in the Wild to Tame Pets

The fact that lion cub photos were being taken up into the 1990s is testament to the enduring demand for them. We find them in many postwar zoos, including Frankfurt, Leipzig, and Berlin. In the latter, visitors could even have their picture taken holding a small lion at one of two zoos: at what was by then the West Berlin Zoo6 or at the East Berlin Tierpark in Friedrichsfelde, which opened in 1955.

This 1962 family photo with a lion cub at Berlin Tierpark is from the private family album of our colleague. (Private, image: Werner Engel. All rights reserved.)

During Germany’s  rebuilding, lion breeding programmes started up again at zoos like Leipzig and Cottbus, and the

rebuilding, lion breeding programmes started up again at zoos like Leipzig and Cottbus, and the  trade in wild animals once more picked up speed in Germany, meaning that lion cubs were more readily available than they had been in the preceding years.

trade in wild animals once more picked up speed in Germany, meaning that lion cubs were more readily available than they had been in the preceding years.

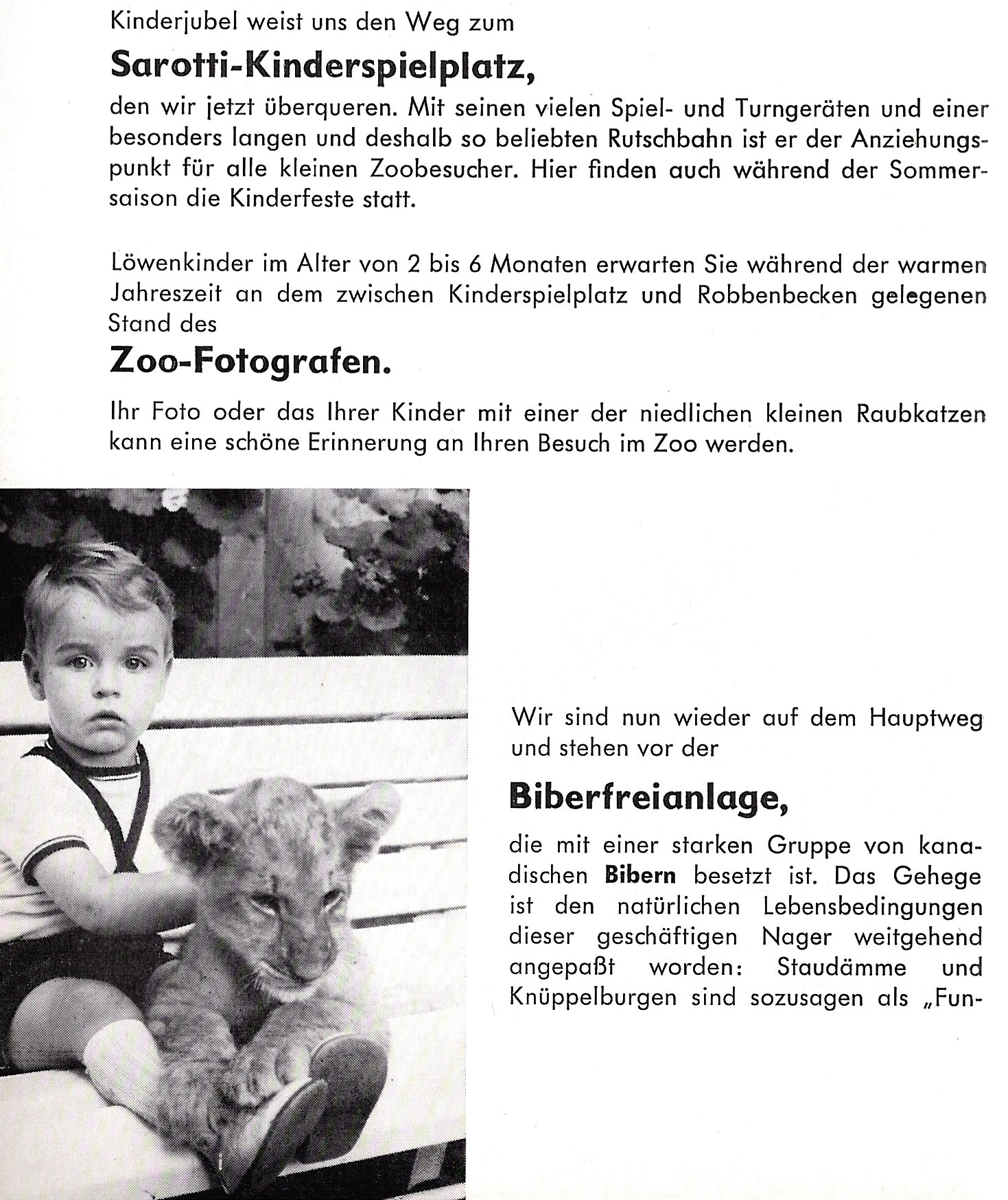

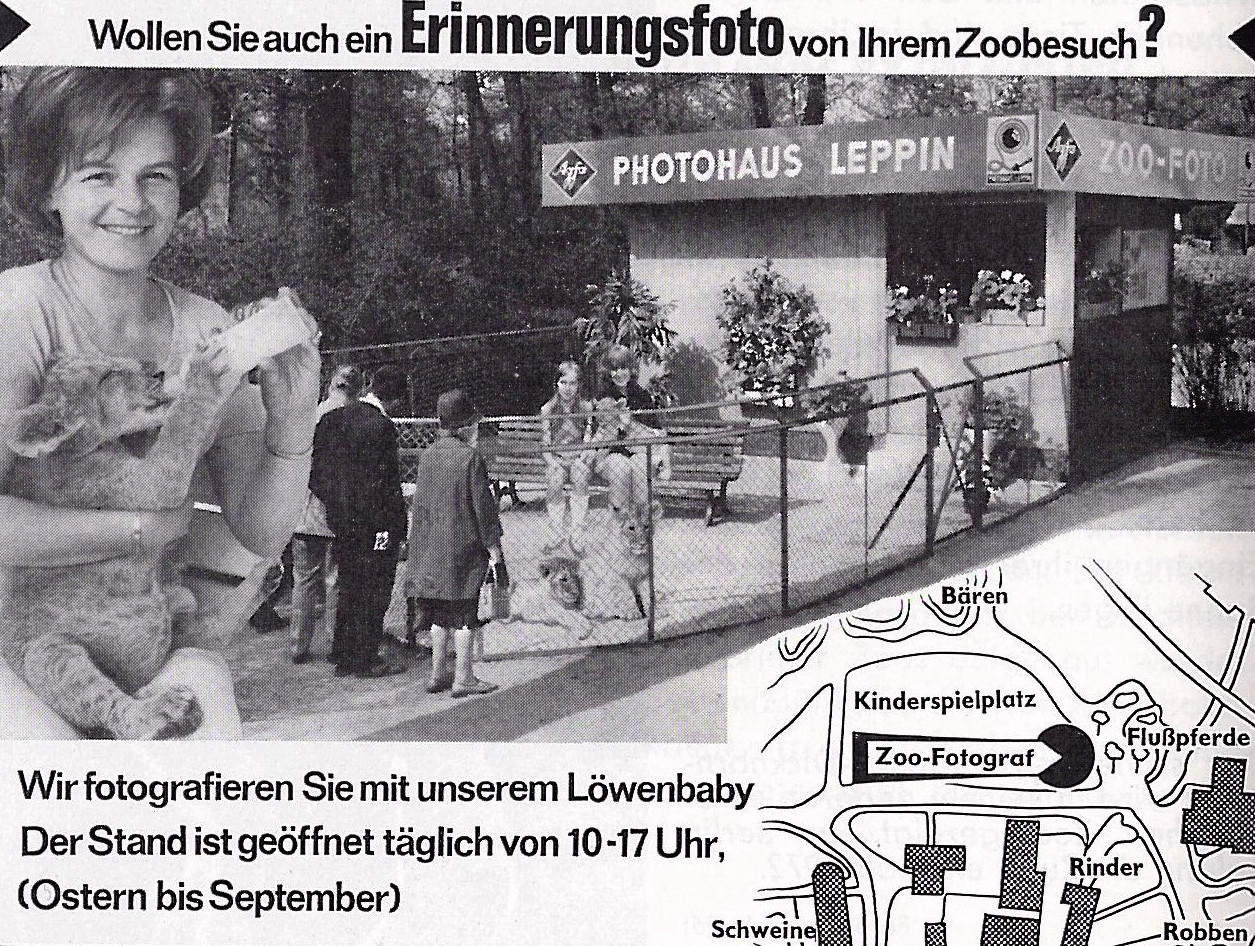

This is what the zoo photographer’s booth looked like at the West Berlin Zoo of the 1970s, where visitors could have their photo taken with lion cubs. Guide to Berlin Zoological Garden, 1973.

Page from the Guide to Berlin Zoological Garden from 1971, advertising the zoo photographer with a photo of a child with lion cub.

In the 1960s, there was a downright boom in lion cub photography as photo booths were set up in the safari and leisure parks being opened far and wide. Christina Wessely attributes this boom to the way humans perceived wild animals, and to the attitudes towards them in 1960s and 1970s Germany. She set out in search of the places where ‘wild animals’ could be found in the (West) German media of the 1960s, and found them in places like the movies, above all in films like Serengeti Shall Not Die by the Frankfurt zoo director Bernhard Grzimek, who had been a councillor in the Reich Ministry of Food and Agriculture during the  Nazi period before going on to become Conservation Officer for the German Federal Government in the 1970s. The film studies scholar Vinzenz Hediger reads this film, which helped to spread the ideas of the conservation movement after the Second World War, as a “piece of late colonial work in mourning”, “staged in the medium of ecological thinking”.7 On the screen, the transition from killing to depicting, from hunting to protecting, is programmatically set in scene. In order to understand the different image politics underpinning these practices, however, we have to go further back in time to big-game hunting and early wildlife and nature conservation programmes in the

Nazi period before going on to become Conservation Officer for the German Federal Government in the 1970s. The film studies scholar Vinzenz Hediger reads this film, which helped to spread the ideas of the conservation movement after the Second World War, as a “piece of late colonial work in mourning”, “staged in the medium of ecological thinking”.7 On the screen, the transition from killing to depicting, from hunting to protecting, is programmatically set in scene. In order to understand the different image politics underpinning these practices, however, we have to go further back in time to big-game hunting and early wildlife and nature conservation programmes in the  German colonies.

German colonies.

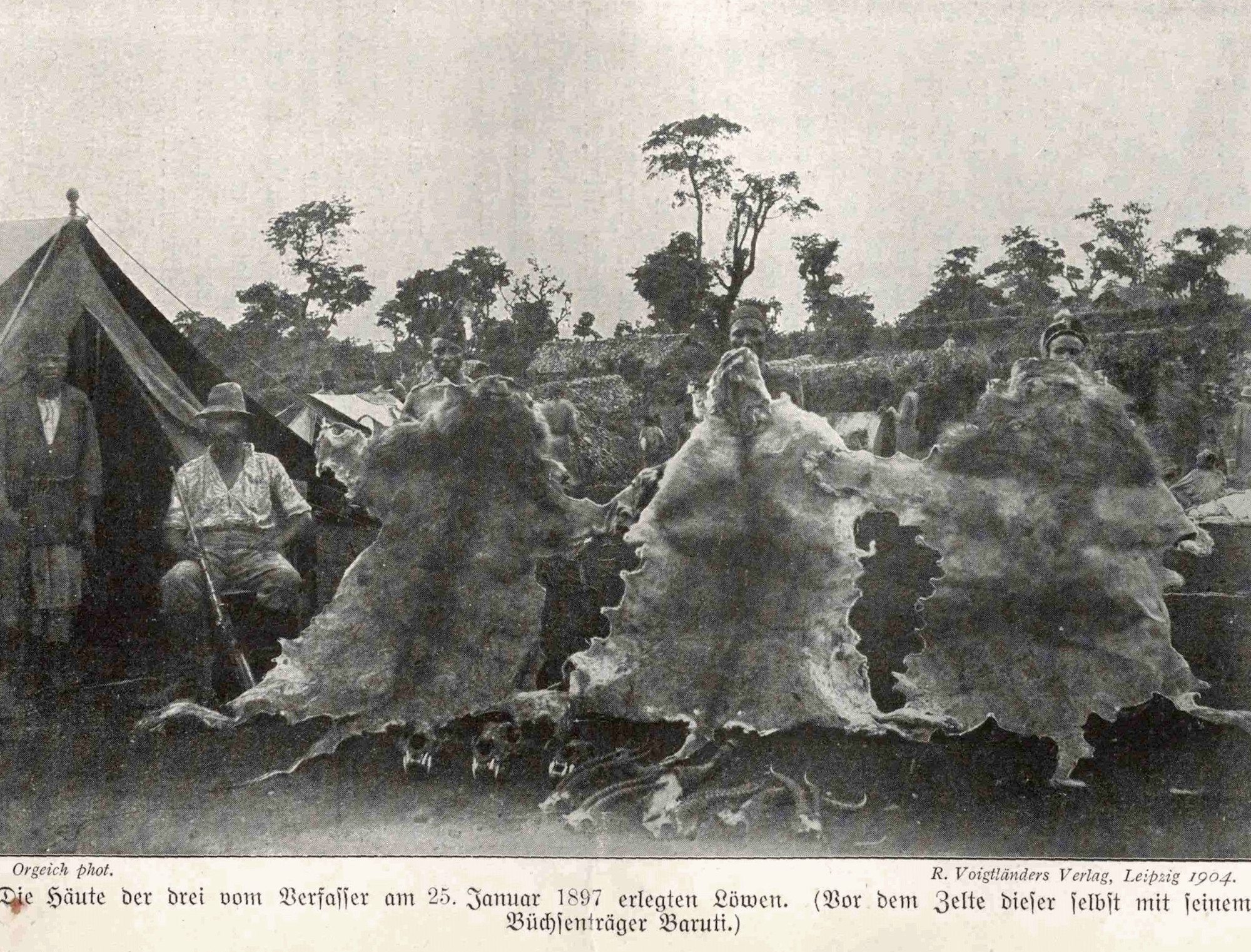

At the beginning of the 20th century, figures like Carl Georg Schillings, one of the most famous German big-game hunters, wildlife photographers, and so-called ‘Africa travellers’, was one of the people propagating a shift from hunting to photography, although for Schillings himself, the two practices – hunting and photography – still existed side by side. As he began photographing animals in the wild and later campaigned for their conservation, he was also killing innumerable lions that ended up as hunting trophies.

In his book Mit Blitzlicht und Büchse (With Flash and Rifle. Leipzig: Voigtländer, 1905), Georg Carl Schillings stages himself beside his prey as a big-game hunter.8

In both cases, the lion played the role of the  charismatic animal par excellence. It was the wild predator and colonial trophy accompanied by colonial iconography and framed by the idea of masculinity embodied by figures like Schillings and Schomburgk.

charismatic animal par excellence. It was the wild predator and colonial trophy accompanied by colonial iconography and framed by the idea of masculinity embodied by figures like Schillings and Schomburgk.

The persistence of this idea is demonstrated by nonfiction volumes like Bwana Simba – Der Herr der Löwen (Bwana Simba – The Lord of the Lions) from 2008.9 Schillings himself already documented the journeys he had taken to Africa at the beginning of the 20th century in books that were widely disseminated – the 1905 Mit Blitzlicht und Büchse alone, with reproductions of over 300 of his own animal photographs, was reprinted several times within the space of just a few years.10 While these volumes still reveal the concurrence of big-game hunting and photo shooting, Grizmek was already completely on the side of photography 50 years later.

In his story of saving animals, animals came closer to humans, both physically and in the cultural imaginary. However, the cinema screen was not necessarily the medium of choice when it came to demonstrating closeness between humans and animals. In the 1950s and 1960s, humans and predators primarily met above all in front of the television camera, which shifted the setting from the wild to the zoo or the TV studio. In programmes like Tierparkteletreff (Zoo Club) und Ein Platz für Tiere (A Place for Animals), the (still  predominantly male) zoo directors held all kinds of animals in their arms or on their laps, as Christina Wessely writes.11

predominantly male) zoo directors held all kinds of animals in their arms or on their laps, as Christina Wessely writes.11

What had the potential to demonstrate the proximity between humans and animals more emphatically than pictures of harmonious, even loving togetherness between man and predator? Posing with (supposedly) tame animals conveyed the image of closeness without the fear of have to directly touch ‘wild animals’. The recordings were made in a completely different register to scenes of predators photographed in the wild in the early 20th century. The gesture of dominance over the captive or slain predator had almost completely fallen out of fashion in the German television of the mid-1950s. Dominance over animals, as the message went, had transformed into a friendship with them.

Juvenile Predators: The Politics of Care

Such images of closeness were present not just on television but also at zoos and had long been so. This is demonstrated by both the animal baby zoo and by the innumerable photos of zoo directors and keepers carrying, feeding, cuddling, and presenting predators at petting zoos, in the private residences of directors, or on zoo benches.

The Leipzig zoo director Karl Max Schneider presents a lion cub to a group of children in 1953 and allows them to touch it. (SLUB Dresden/Deutsche Fotothek, image: Roger Rössing und Renate Rössing. All rights reserved.)

These images fanned the idea of the lion as a tame cat, as did the books published by a large number of zoo directors and keepers giving accounts of their experiences, like Mit Löwen und Tigern unter einem Dach (With Lions and Tigers under One Roof) or Affen im Haus (Apes in the House).12 At the zoo, proximity to the animals was associated with animal husbandry. Juvenile animals were particularly well suited to conveying this idea, because what embodies the idea of care better than an animal baby being fed by hand? Visitors were even allowed to give it a go themselves: what  animal baby zoos had offered before the war – when even the smallest visitors had been able to drill family roles by feeding young predators13 – was now being continued in lion cub photos.

animal baby zoos had offered before the war – when even the smallest visitors had been able to drill family roles by feeding young predators13 – was now being continued in lion cub photos.

Children feeding animals at Berlin’s ‘baby animal zoo’. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

The zoo photographer also advertised feeding scenes in the 1973 Guide to Berlin Zoological Garden.

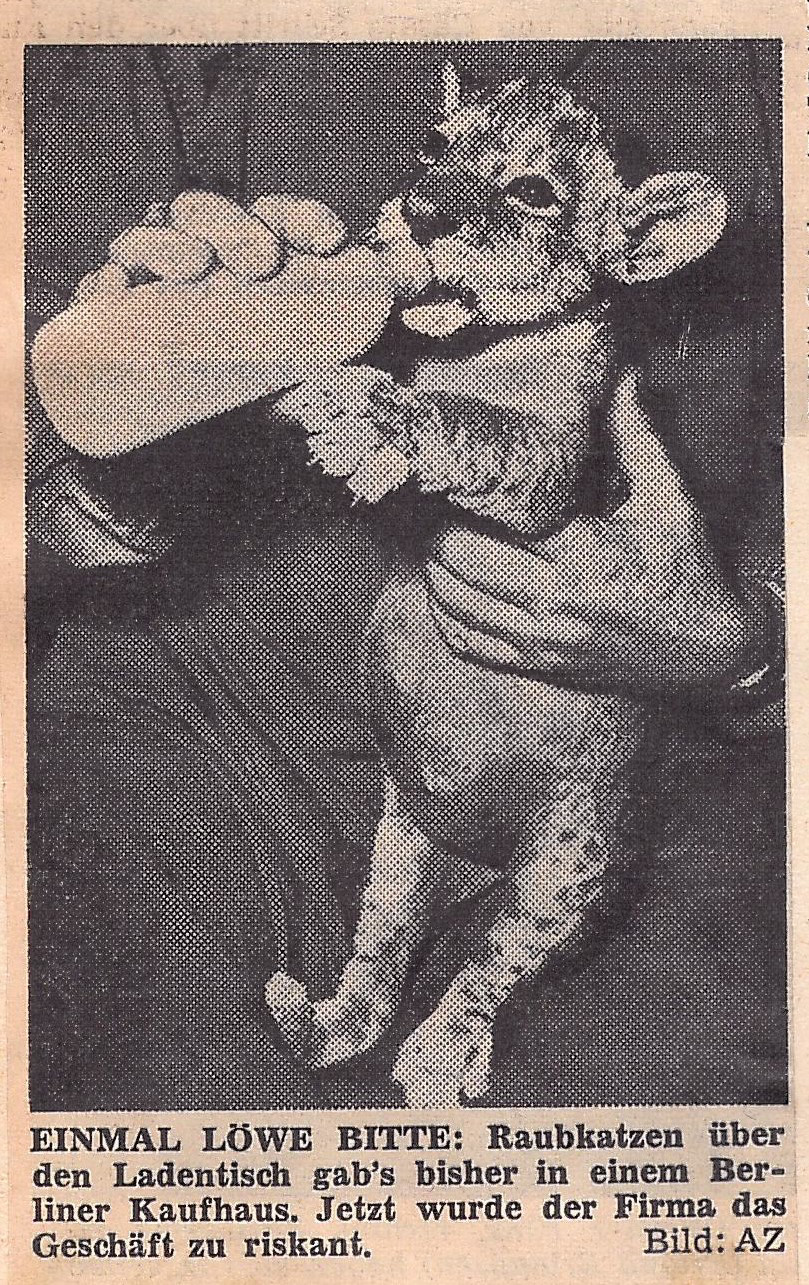

The animal baby zoo and the photo booth, which gave visitors an opportunity to touch and feed animal babies, as well as media representations of zoo directors with (supposedly) tame predators, probably all contributed to the idea of juvenile predators as pets or stuffed toys – harmless animals that could easily be kept as pets.14 Although lion cubs were predators, they were first and foremost juvenile animals that visitors could stroke, feed, or hold in their arms. This is certainly what Berlin’s Wertheim department store seems to have believed when it had the idea of putting lion cubs up for sale in its zoo department in 1969. For 1,600 to 1,880 marks, people could order department store lions to be delivered with accompanying care instructions.15

In 1969, the Berlin Wertheim department store briefly had lion cubs in its product range, as the Tagesspiegel reported on 30 August 1969.

However, one week later, sales were abandoned after Berlin Zoo apparently warned that “a cute lion cub” could grow into a powerful big cat within three months.16 But other department stores with ‘wild animals’ on offer persevered. Harrods Pet Kingdom in London, which opened in 1917, could grant almost any wish, from tigers and panthers to baby elephants, lions, and alligators. In 1976, the Endangered Species Act forced the department store to reduce its product range, but the animal department did not permanently close its doors until 2014.17 Regardless, keeping predators in private homes is still in fashion and suggests that the long tradition of lion cub pictures has influenced the idea of predators as pets and ‘stuffed animals toys’.

Behind the Pictures: Image and Breeding Economies

The fact that it was only juvenile animals being depicted in zoo lion cub photos was not just due to the cuddly animal factor.18 The little lions were soon too big to interact with humans safely. The animals were not allowed to be more than two to six months old19 and were therefore only suitable as “photography lions”, as the Berlin zoo director  Katharina Heinroth describes the juvenile animals in a 1951 letter,20 for a limited period of time. The age limit for the job as a ‘photography lion’ created a constant demand for young animals.21 Lion cub pictures that seem to show the same lion again and again therefore depended on zoos and photographers being able to procure lion cubs from animal dealers or from other zoos.

Katharina Heinroth describes the juvenile animals in a 1951 letter,20 for a limited period of time. The age limit for the job as a ‘photography lion’ created a constant demand for young animals.21 Lion cub pictures that seem to show the same lion again and again therefore depended on zoos and photographers being able to procure lion cubs from animal dealers or from other zoos.

Where did the lion cubs come from? Since the founding of zoological gardens in the 19th century, lions had been one of their main attractions. Around 1890, as the Berlin zoo director Ludwig Heck later recalled, “imported original lions”, i.e., that had been caught  in the wild, were still a sensation and came with a corresponding price tag.22 In 1890, the Alfeld animal dealer Carl Reiche, for example, requested 5000 marks for a lion imported from South Africa in 1890, which Antwerp Zoo was prepared to pay. In the mid-1930s, when zoos were opening their first photo booths, the situation had changed: Heck was now writing about “masses of lions” from the wild and in-house breeding programmes, and zoos barely knew what to do with all the lions, which were being bred on an almost “factory-like scale”. Leipzig Zoo in particular had gained the reputation of being a “veritable lion factory”,23 supplying other zoos and the odd zoo photographer with lion cubs.24

in the wild, were still a sensation and came with a corresponding price tag.22 In 1890, the Alfeld animal dealer Carl Reiche, for example, requested 5000 marks for a lion imported from South Africa in 1890, which Antwerp Zoo was prepared to pay. In the mid-1930s, when zoos were opening their first photo booths, the situation had changed: Heck was now writing about “masses of lions” from the wild and in-house breeding programmes, and zoos barely knew what to do with all the lions, which were being bred on an almost “factory-like scale”. Leipzig Zoo in particular had gained the reputation of being a “veritable lion factory”,23 supplying other zoos and the odd zoo photographer with lion cubs.24

The ways in which the animals were entangled within economies of trade and bartering is demonstrated by a letter from Berlin Zoo director Katharina Heinroth to the director of Leipzig Zoo in 1951: “We were gifted an approximately four-month-old female lion by the Kyriazi cigarette company”, writes Heinroth. These kinds of animal gifts, for which the giver usually wanted to be explicitly acknowledged by name, turned zoo animals into advertising media that closely linked the animal and the product in zoo visitors’ perception. The animal was clearly supposed to be used as a ‘photography lion’, but shortly after it arrived, it had already been discarded again because, at four months old, it was already “too old to serve as a photography lion. She is very prickly, and our photographer is crying out for a small lion.”25 Leipzig Zoo director Max Schneider promised her a specimen from his breeding programme, in return for which he received flamingos to the value of 300 marks. This clearly shows how zoo management helped the photographer to obtain and later get rid of young lions. Katharina Heinroth was probably thinking about the publicity the zoo photographer could generate for her zoo, which was still in the process of being  rebuilt. At Berlin Tierpark, too, which was opened in 1955, the privately run photo booth purchased most of its six-week-old animals from the bastions of East German lion breeding, the zoos in Leipzig and Cottbus. The photographer fed the animals by bottle until, at the age of three months, they could be used for a while in photos.26 The only way to produce images on the basis of the continuous ‘consumption’ of animals, especially in order to serially (re-)produce the same motif, was by means of reproduction, meaning that the production of images was closely linked to the ‘almost factory-like’ breeding techniques.

rebuilt. At Berlin Tierpark, too, which was opened in 1955, the privately run photo booth purchased most of its six-week-old animals from the bastions of East German lion breeding, the zoos in Leipzig and Cottbus. The photographer fed the animals by bottle until, at the age of three months, they could be used for a while in photos.26 The only way to produce images on the basis of the continuous ‘consumption’ of animals, especially in order to serially (re-)produce the same motif, was by means of reproduction, meaning that the production of images was closely linked to the ‘almost factory-like’ breeding techniques.

The Critique Gets Louder

It was precisely these issues that brought lion cub photography under fire in the 1980s. There was a noticeable increase in the number of enquiries and complaints landing on the desks of zoo administrations in this period, and it is probably no coincidence that this was happening as the environmental movement began to gain ground. Most authors were concerned that the animals were not being treated in a  species-appropriate way. Animal rights activists and zoo visitors were now increasingly denouncing the way that ‘photography lions’ were being kept. Some of them wanted to know where the animals came from, others where they would go once they had grown out of the ‘cuddly age’ and could not be used anymore.27 A number of visitors claimed that they had noticed that the lions were “lying around apathetically, looking sleepy” and that they had clearly been sedated. One particularly committed author threatened to report the zoo to animal welfare.28 The author’s critique was also directed at “animal keeping practices” and did not beat about the bush when it came to their suspicions regarding the (ill) treatment of the animals. At the same time, critique was being directed at the motif itself, which leads back to the politics of images. For “photos suitable for family albums”, the “lion is presented as a kind of ‘lap dog’” – a belittlement of the animals which, for pedagogical reasons, should be rejected, as the author argued.29 When viewing these kinds of photos, some people were reminded of the practices of “thoughtless, profit-greedy photographers in various holiday countries“,30 while others went so far as to accuse the photographer of the capitalistic “exploitation of the animals” and deliberately placed their critique within a larger conservation context:

species-appropriate way. Animal rights activists and zoo visitors were now increasingly denouncing the way that ‘photography lions’ were being kept. Some of them wanted to know where the animals came from, others where they would go once they had grown out of the ‘cuddly age’ and could not be used anymore.27 A number of visitors claimed that they had noticed that the lions were “lying around apathetically, looking sleepy” and that they had clearly been sedated. One particularly committed author threatened to report the zoo to animal welfare.28 The author’s critique was also directed at “animal keeping practices” and did not beat about the bush when it came to their suspicions regarding the (ill) treatment of the animals. At the same time, critique was being directed at the motif itself, which leads back to the politics of images. For “photos suitable for family albums”, the “lion is presented as a kind of ‘lap dog’” – a belittlement of the animals which, for pedagogical reasons, should be rejected, as the author argued.29 When viewing these kinds of photos, some people were reminded of the practices of “thoughtless, profit-greedy photographers in various holiday countries“,30 while others went so far as to accuse the photographer of the capitalistic “exploitation of the animals” and deliberately placed their critique within a larger conservation context:

“We are now horrified that this kind of animal torture can take place at our zoo before your eyes. Has it escaped your attention that there has been a change of thinking in the population, that more and more people are campaigning for animals and the environment?”31

Zoo management passed the critique on to the photographer and also communicated to the critics that sufficient breaks and species-appropriate feed had been ensured. The zoo claimed that it was not about profit, but about providing a special experience that took place in a “direct encounter between human and animal, particularly between human child and animal baby”, which could not be replaced by any textbook or film.32 But it was precisely the direct proximity to the animal that, in the eyes of many visitors, was out of date, and which they no longer saw as an expression of animal friendship. This development intensified and had a direct impact on how zoos saw themselves. The idea of the animal friend had long been undergoing change and had transitioned, as Christina Wessely writes, from the pushy pathos of animal friendship that did not shy away from touch to a paradigm of restrained care:

“In the age of ecological consciousness, by the turn of the 21st century at the latest, the ultimately quite pushy animal friend abdicated. During this transformation, lion cub photos gradually disappeared as they were now seen as troublesome souvenirs of encounters with nature that were not supposed to be remembered in that way anymore.”33

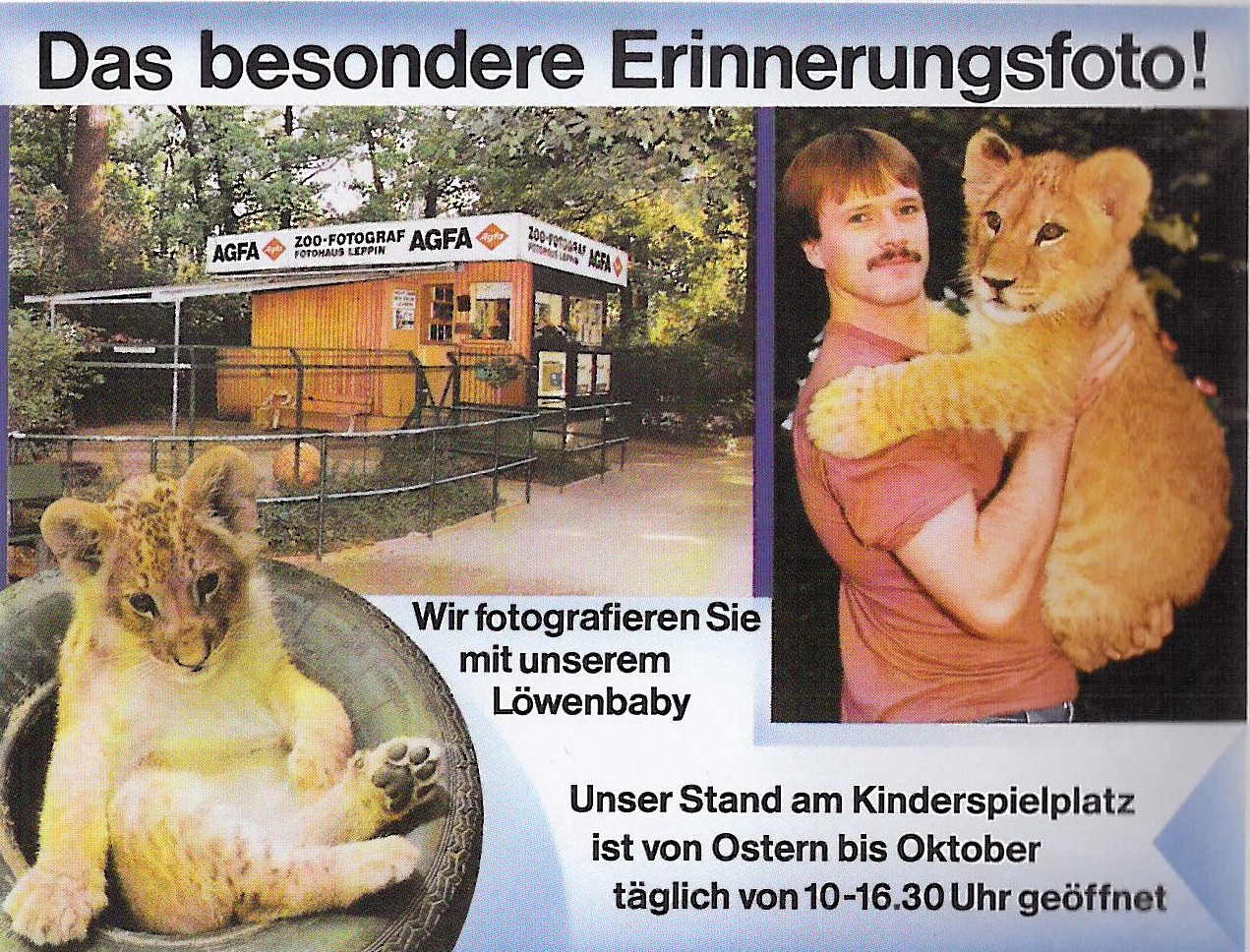

This was added to by the fact that, since the beginning of the 1980s, most zoos had done away with the fees for private photography. While Director Heinrich Dathe had been providing visitors with tips on finding beautiful motifs and the right time of day in his guides since the 1960s, at West Berlin Zoo, a permit to take photos during the day still cost 0.50 marks. But the following year, independent photography was “permitted and desired”, as a zoo guide reads.34 The lion cub photographs of the photo booths hung around for another decade. Although the photography booth was still being presented in colour photography in a 1990/91 advertisement and the sitting woman had been replaced by a man holding a lion cub in his arms, in 1994, all that remained was the sentence: “Taking photos and being photographed... Your zoo photographer is here for you.”35

The Zoo Guide drew attention to the zoo photographer’s booth in the 1970s with a picture of a lion cub.

In 1992, the guide still contained an advertisement, now with a colour photograph, for souvenir photos with lion cubs, before the lion cubs ultimately disappeared in 1994.

However, the booth has now disappeared from the zoo. What remains is a collection of old lion cub photos – which we discover at flea markets, in archives, on eBay, and in private family albums. The identities of the humans and the histories of the animals in these photos can seldom be reconstructed, like in this undated photo from Berlin Zoo.

Undated photo of a girl with a lion cub, taken by the photographer at West Berlin Zoo. (Private. All rights reserved.)

What connects them is what stays the same, a motif that can be traced through a history of 70 years, giving it a serial character. And while the lion cub photos now seem like relicts, they have long been replaced. The contact between humans and young predators has conquered  new spaces. This includes the booming wildlife tourism in numerous countries, where the business model is based on providing the experience of touch and taking home holiday photos as souvenirs. The keeping of predators in private residences is experiencing another (or a continued) boom. According to the WWF, more tigers lived in private US households in 2014 than in the wild.36 The current media transformation of lion cub photographs is also demonstrated by series like Tiger King and by the success of the innumerable private photos with juvenile predators circulating on social media. Much of the critique being voiced in these contexts is reminiscent of the critique given by the zoo public in the 1980s, once more revolving around the issue of how animals are caught and kept, about the work animals do, and the economies behind them.37 And once more, the criticism being directed at this motif is about the politics of animal images and about the reproduction of exoticisms, just as it is about the relationship between animals and humans (that is staged in images). So, although the settings and forms of media dissemination have changed and zoo lion cub photography has already become historical, the questions that it raises are still topical.

new spaces. This includes the booming wildlife tourism in numerous countries, where the business model is based on providing the experience of touch and taking home holiday photos as souvenirs. The keeping of predators in private residences is experiencing another (or a continued) boom. According to the WWF, more tigers lived in private US households in 2014 than in the wild.36 The current media transformation of lion cub photographs is also demonstrated by series like Tiger King and by the success of the innumerable private photos with juvenile predators circulating on social media. Much of the critique being voiced in these contexts is reminiscent of the critique given by the zoo public in the 1980s, once more revolving around the issue of how animals are caught and kept, about the work animals do, and the economies behind them.37 And once more, the criticism being directed at this motif is about the politics of animal images and about the reproduction of exoticisms, just as it is about the relationship between animals and humans (that is staged in images). So, although the settings and forms of media dissemination have changed and zoo lion cub photography has already become historical, the questions that it raises are still topical.

- See the Zoo Guides of 1936, 1938, and 1940; see also Ludwig Heck. “Zootiere einst und jetzt”, January 1934, AZGB N 1/7. I am unaware of when exactly the photo booth at Berlin Zoo was opened.↩

- Hildegard Zukowsky. “Löwenprinzchen”. CHITuMW 1, no. 6 (1926): 132-134, quoted in: Nastasja Klothmann. Gefühlswelten im Zoo: Eine Emotionsgeschichte 1900-1945. Bielefeld: transcript, 2015: 291.↩

- Each zoo dealt with the permission to take photos differently. While visitors in Leipzig, Halle, Berlin, and Vienna had to purchase a permit, visitors to other zoos could take photos free of charge. Cf. 40. Konferenz der Direktoren mitteleuropäischer Zoologischer Gärten in Breslau vom 23. bis 25. August 1928, AZGB V 1/10.↩

- Zoologischer Garten Berlin. Wegweiser durch den Zoologischen Garten Berlin. Berlin: 1938.↩

- Christina Wessely. Löwenbaby. Berlin: Matthes & Seitz, 2019.↩

- After the war, the booth moved from its site beside the predator enclosure to the bear enclosure. Cf. Katharina Heinroth. Der Zoologische Garten Berlin: Zweiter Bericht und Wegweiser nach dem Kriege. Berlin: Aktien-Verein des Zoologischen Gartens Berlin, 1956: 6.↩

- Vinzenz Hediger. “Das Tier auf unserer Seite: Zur Politik des Filmtiers am Beispiel von ‘Serengeti darf nicht sterben’”. In Politische Zoologie. Anne von Heiden und Joseph Vogl (eds.). Zurich/Berlin, 2007: 287-301. Historians like Thomas M. Lekan, Angela Thompsell, and Bernhard Gißibl have made similar arguments. Cf. Thomas M. Lekan. Our Gigantic Zoo: A German Quest to Save the Serengeti. New York: Oxford University Press, 2020; Angela Thompsell. Hunting Africa: British Sport, African Knowledge and the Nature of Empire. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015; Bernhard Gißibl. The Nature of German Imperialism: Conservation and the Politics of Wildlife in Colonial East Africa. The Environment in History: International Perspectives, Volume 9. New York: Berghahn Books, 2016.↩

- It is part of the visual staging of many European big-game hunters to neither name local actors nor to give them an equal place in the image.↩

- Manfred Becker. Bwana Simba: Der Herr der Löwen; Carl Georg Schillings, Forscher und Naturschützer in Deutsch-Ostafrika. Düren: Hahne & Schloemer Verlag, 2008.↩

- Carl Georg Schillings. Mit Blitzlicht und Büchse: Neue Beobachtungen und Erlebnisse in der Wildnis inmitten der Tierwelt von Äquatorial-Ostafrika. Leipzig: R. Voigtländer, 1905.↩

- Ein Platz für Tiere is still one of Germany’s most successful television animal series ever and ran for 31 years with 175 episodes.↩

- Karl Max Schneider. Mit Löwen und Tigern unter einem Dach. Wittenberg: Ziemsen, 1957; Bernhard Grzimek. Affen im Haus und andere Tierberichte. Stuttgart: Franck’sche Verlagshandlung, 1951.↩

- “Das Lieblingsspiel all dieses Kleinzeugs ist, sich füttern zu lassen, und die kleinen Menschenkinder sind ganz begeistert von dem unermüdlichen Appetit der kleinen Tierkinder.” (“The favourite game of all these little animals is being fed, and the little human children adore the unremittable appetites of the little animal children.”) “Lebendes Tier-Spielzeug”. Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung no. 30, 26.07.1931: 1272.↩

- According to Nastasja Klothmann, zoological gardens like Leipzig Zoo were selling young predators to private citizens before the Second World War and raffling off wild animals. Cf. Klothmann, 2015: 228-231.↩

- Cf. “Löwen mit Gebrauchsanweisung: Neues Angebot im Warenhaus: Kleine Raubkatzen von 1600 Mark an”. Tagesspiegel, 30.08.1969.↩

- “Keine Löwen mehr über den Ladentisch”. Harsfelder Zeitung, 05.09.1969.↩

- Cf. “Harrods Pet Shop”. Daily Mail Reporter, 11.01.2014. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2537568/Harrods-pet-shop-sold-alligators-lions-baby-elephant-Ronald-Reagan-set-close-100-years.html.↩

- Mature lions, on the other hand, are more or less associated with the wilderness and (colonial) big game.↩

- See, e.g., Heinz-Georg Klös. Wegweiser durch den Zoologischen Garten Berlin 1958, Aktien-Verein des Zoologischen Gartens Berlin (ed.). Berlin: 1958: 56.↩

- K. Heinroth to K.M. Schneider, 23.05.1951, AZGB O 0/1/284.↩

- New animals were provided by the animal trade or by swapping with other zoos. See, e.g., “Tätigkeitsbericht von Katharina Heinroth in der Aufsichtsratssitzung vom 07.12.1951”, AZGB N 4/2.↩

- L. Heck to H. Heck, 09.01.1934, AZGB N 1/7.↩

- L. Heck to H. Heck, 09.01.1934, AZGB N 1/7. See also Mustafa Haikal. Die Löwenfabrik: Lebensläufe und Legenden. Leipzig: Pro Leipzig, 2006; Mustafa Haikal and Jörg Junhold. Auf der Spur des Löwen: 125 Jahre Zoo Leipzig. Leipzig: pro Leipzig, 2003.↩

- In turn, zoos had to get rid of lions that were too big, resulting lion cubs being circulated in a manner similar to an economy of trade or barter.↩

- K. Heinroth to K.M. Schneider, 23.05.1951, AZGB O 0/1/284.↩

- “I bought the babies from various zoos for 1000 GDR marks per lion.” He bought a total of around 50 lions, which he then donated to the zoos in the GDR a few months later. Cf. “Michael Barz lüftet das Geheimnis um die Löwen-Babys vom Tierpark”. B.Z., 06.01.2016.↩

- According to management, the photographer gave the growing lion cubs away to other West German zoos.↩

- See, e.g., anonymous letter to Berlin Zoological Garden, 23.08.1989, AZGB O 0/1/9.↩

- See, e.g., B. Degenkolbe to Berlin Zoological Garden, August 1987, in: AZGB O 0/1/9.↩

- Anonymous letter to Berlin Zoological Garden, 23.08.1989, AZGB O 0/1/9.↩

- G. Philipp to H.-G. Klös, April 1988, AZGB O 0/1/41.↩

- B. Blaskiewitz to G. Philipp, 07.04.1988, AZGB O 0/1/41.↩

- Wessely, 2019: 59, 61.↩

- An annual photography permit cost 10 marks and annual photography permits for the zoo and aquarium 15 marks. Cf. Heinz-Georg Klös. Wegweiser durch den Zoologischen Garten Berlin 1981. Berlin: Aktien-Verein des Zoologischen Gartens Berlin, 1981.↩

- Hans Frädrich (ed.). Wegweiser durch den Zoologischen Garten Berlin und sein Aquarium 1994. Aktien-Verein des Zoologischen Gartens Berlin, 1994.↩

- “More Tigers in American Backyards than in the Wild”. WWF Stories, 29.07.2014. https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/more-tigers-in-american-backyards-than-in-the-wild. On the (frequently illegal) trade in ‘exotic pets’, see Collard, Rosemary-Claire. Animal Traffic: Lively Capital in the Global Exotic Pet Trade. Durham: Duke University Press, 2020.↩

- See, e.g., Natasha Daly. “Wundervolle Fotos – unsichtbares Leid”. National Geographic: (Das Tier und Wir) 6, no. 51 (2019): 40-73.↩