Male orangutan “Enche”, 2016. (Zoologischer Garten Berlin. All rights reserved.)

Visitors of modern zoos love orangutans and other primates. Their human-like appearance makes for great ‘show value’. 1

Fascination with primates in general and orangutans in particular spread among Berliners from the 1870s onwards. In 1876 they were able to marvel briefly at both the first adult orangutan in Europe (in what was then the Unter den Linden Aquarium) and several juveniles (in the Zoological Garden).2

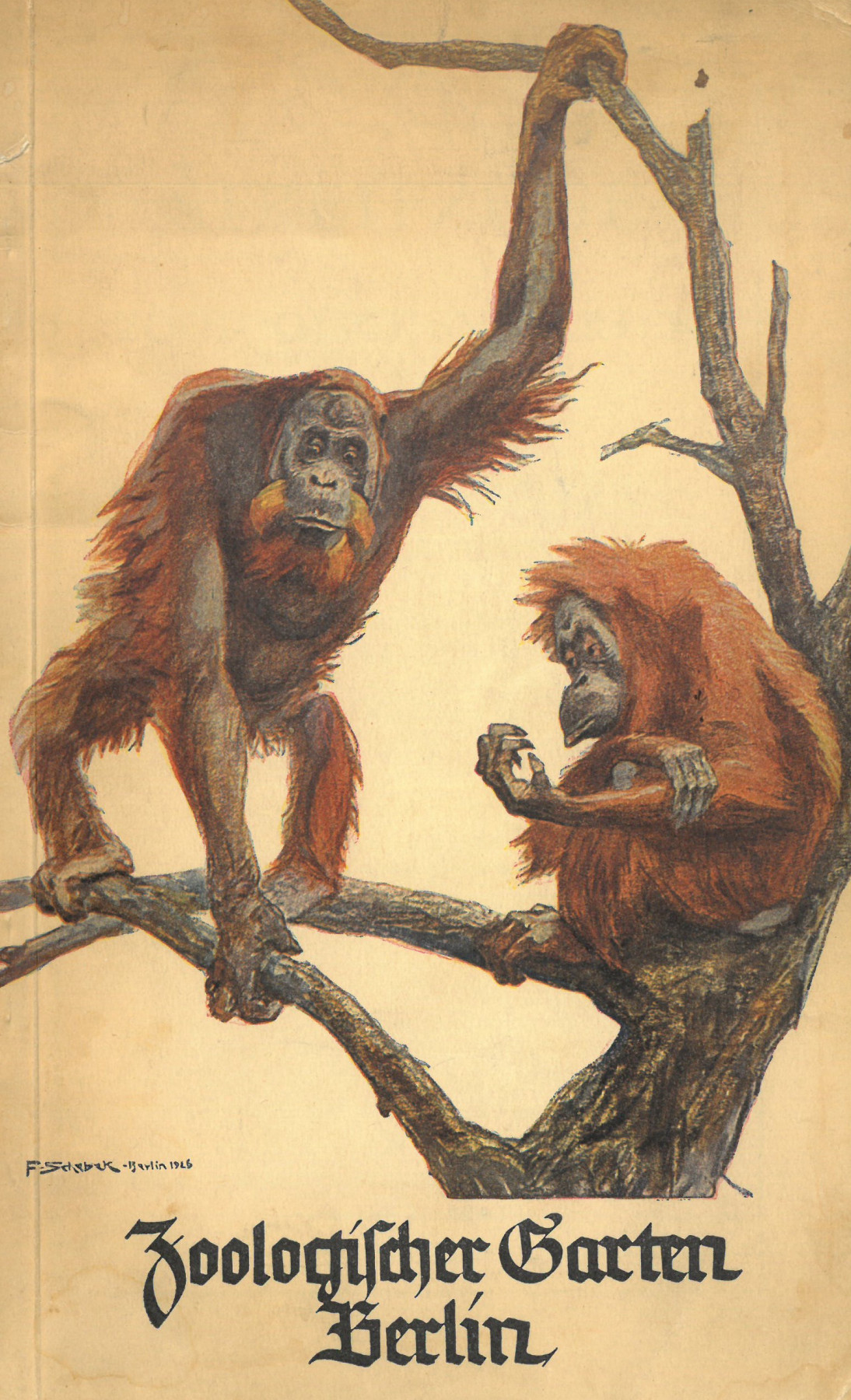

After many years of mostly acquiring individual animals, a pair of Sumatran orangutans came to Berlin for the first time in 1926. Their offspring made headlines, but died shortly after birth.3 For the zoo, these were significant animals – they were featured on the cover of the zoo guide a year after their arrival.

Cover picture of the guide through the Zoological Garden Berlin 1927 with two orangutans.

However, breeding them did not work at first. The  zoo’s records at the time and the so-called

zoo’s records at the time and the so-called  Steinmetz Card Index show that a cub born in 1928 died after one month. Another one, born in 1930, died after three years.4 Thus, all other animals of this species presented at Berlin Zoo continued to be wild-caught. This was no different in other German and European zoos. In the early 1960s, however, this form of

Steinmetz Card Index show that a cub born in 1928 died after one month. Another one, born in 1930, died after three years.4 Thus, all other animals of this species presented at Berlin Zoo continued to be wild-caught. This was no different in other German and European zoos. In the early 1960s, however, this form of  procurement of zoo animals was to ignite a controversy among German and international zoo managers.

procurement of zoo animals was to ignite a controversy among German and international zoo managers.

Protection or Breeding?

In its habitat, the forests of Borneo and Sumatra, the orangutan population has been classified for many years as seriously threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). This is primarily caused by man-made habitat loss through deforestation – especially for palm oil plantations. The majority of orangutans living in zoos in Europe and North America today come from the captive breeding programmes undertaken by zoo associations. But this was not always the case. The example of this species is a good illustration of zoos’ conflicts of interest. Should zoos do without species that are popular with the public but endangered in their natural habitats, or could catching, showing and breeding the animals contribute to their conservation?

The orangutan became a political issue in both German states. The 1962 meeting of the Association of German Zoo Directors took place one year after the construction of the Berlin Wall. Hence, the East German colleagues were absent. During this meeting the ethical aspects of the purchase of wild-caught orangutans were discussed intensively for the first time. The Frankfurt zoo director Bernhard Grzimek pointed out the great endangerment of the species on Borneo and Sumatra and demanded a voluntary renunciation of the import of the species by the assembled zoo directors.5

He anticipated that zoological gardens would otherwise have to reckon with attacks from the public, which knew about the animals’ endangered status through the press. The zoo directors passed a resolution, albeit not unanimously, to:

“immediately join at any time an international decision stopping the purchase of imported [sic!] orangutans, except under very specific provisions to be regulated internationally.”6

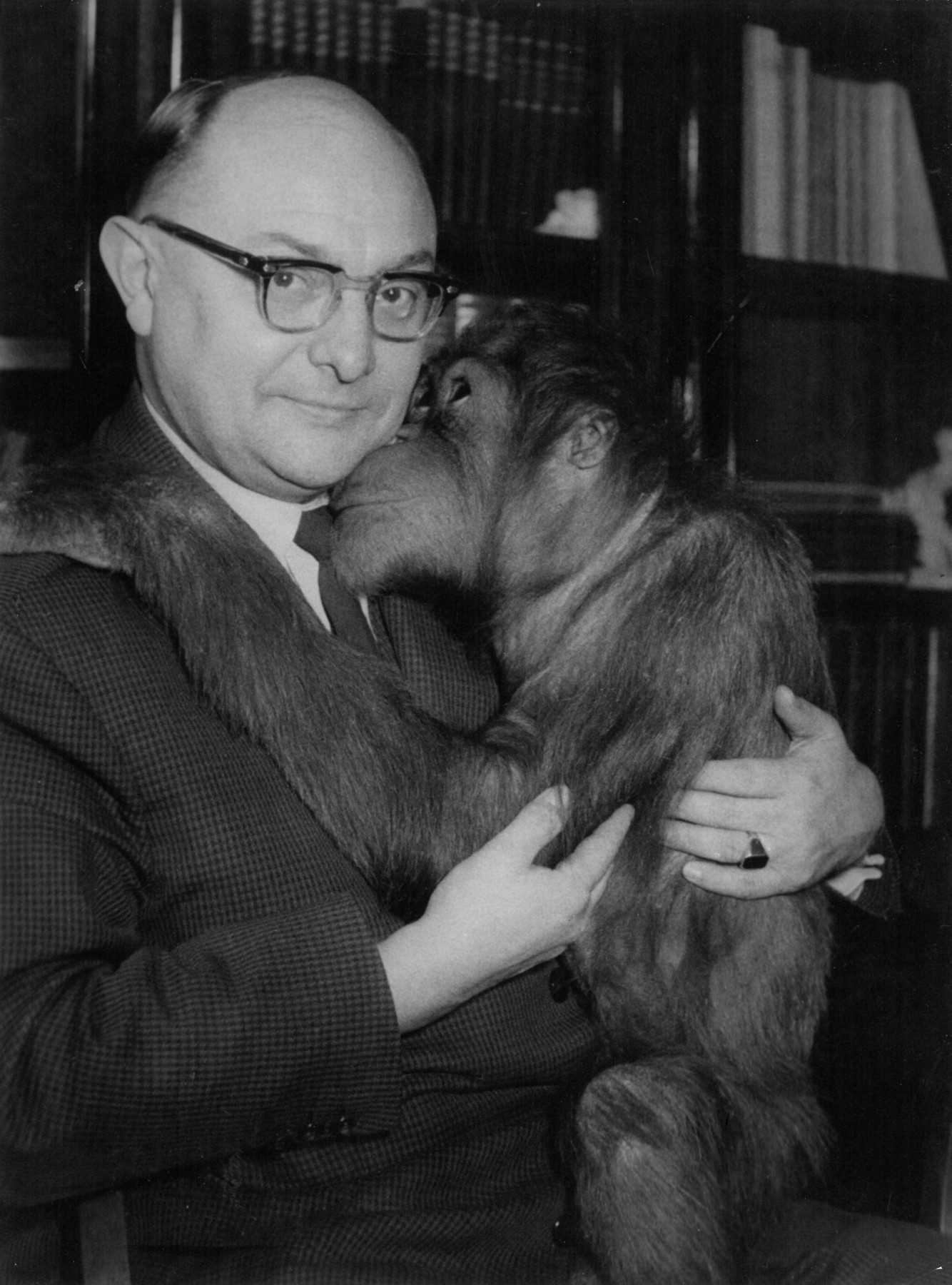

In 1965, the zoo directors met again, this time including representatives from West and East Germany. And again, they discussed the protection of orangutans. The East Berlin zoo director Heinrich Dathe now pleaded that all German zoos should wait for the decision of the conference of the International Union of Directors of Zoological Gardens (IUDZG) taking place the same year.7 He might have expected that the import ban on orangutans, which he disagreed with, would be rejected.

At that conference, Dathe duly spoke out against a ban on keeping and trading endangered species – even if they had not yet been successfully bred in zoos. He argued that private zoos outnumbered zoos organised in associations and would hardly comply with the ban. The task was, in his eyes, for scientific zoos to improve breeding methods. Although his friend and colleague Bernhard Grzimek and others advocated that animals classified as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List – such as the orangutan – should no longer be purchased, Dathe held fast to his opposition. The minutes stated:

“Prof. Dr. Dathe stated that it was irresponsible to prevent the purchase of endangered species because such animals would thus fall into much less able hands. Zoos should rather try to breed them.”8

Heinrich Dathe with orangutan “Jussup”, 1961 (Photo archive Tierpark Berlin, image: Werner Engel. All rights reserved).

West Berlin colleague Heinz-Georg Klös agreed with Dathe.9 And he was not the only one. With respect to their prominently propagated function as institutions that protect animals, it becomes apparent that Klös and Dathe – and many other zoo directors – struggled with a fundamental trade-off. Keeping  great apes brought and still brings zoos considerable prestige in professional circles. These animals also played a role in the rivalry between the two zoos in the divided city. Both the zoo and the animal park had bought wild-caught animals in previous years and were trying, so far unsuccessfully, to breed their own. Hence, both had publicly committed themselves to species conservation, but there was undoubtedly competition for these popular animals. Despite the lack of resources in the GDR, Heinrich Dathe had succeeded in building an ape house, which opened in 1964. It also housed three orangutans – one female and two males.10 He presumably hoped to establish a breeding programme, yet at the same time he must have been aware that more individuals were needed for it to work.

great apes brought and still brings zoos considerable prestige in professional circles. These animals also played a role in the rivalry between the two zoos in the divided city. Both the zoo and the animal park had bought wild-caught animals in previous years and were trying, so far unsuccessfully, to breed their own. Hence, both had publicly committed themselves to species conservation, but there was undoubtedly competition for these popular animals. Despite the lack of resources in the GDR, Heinrich Dathe had succeeded in building an ape house, which opened in 1964. It also housed three orangutans – one female and two males.10 He presumably hoped to establish a breeding programme, yet at the same time he must have been aware that more individuals were needed for it to work.

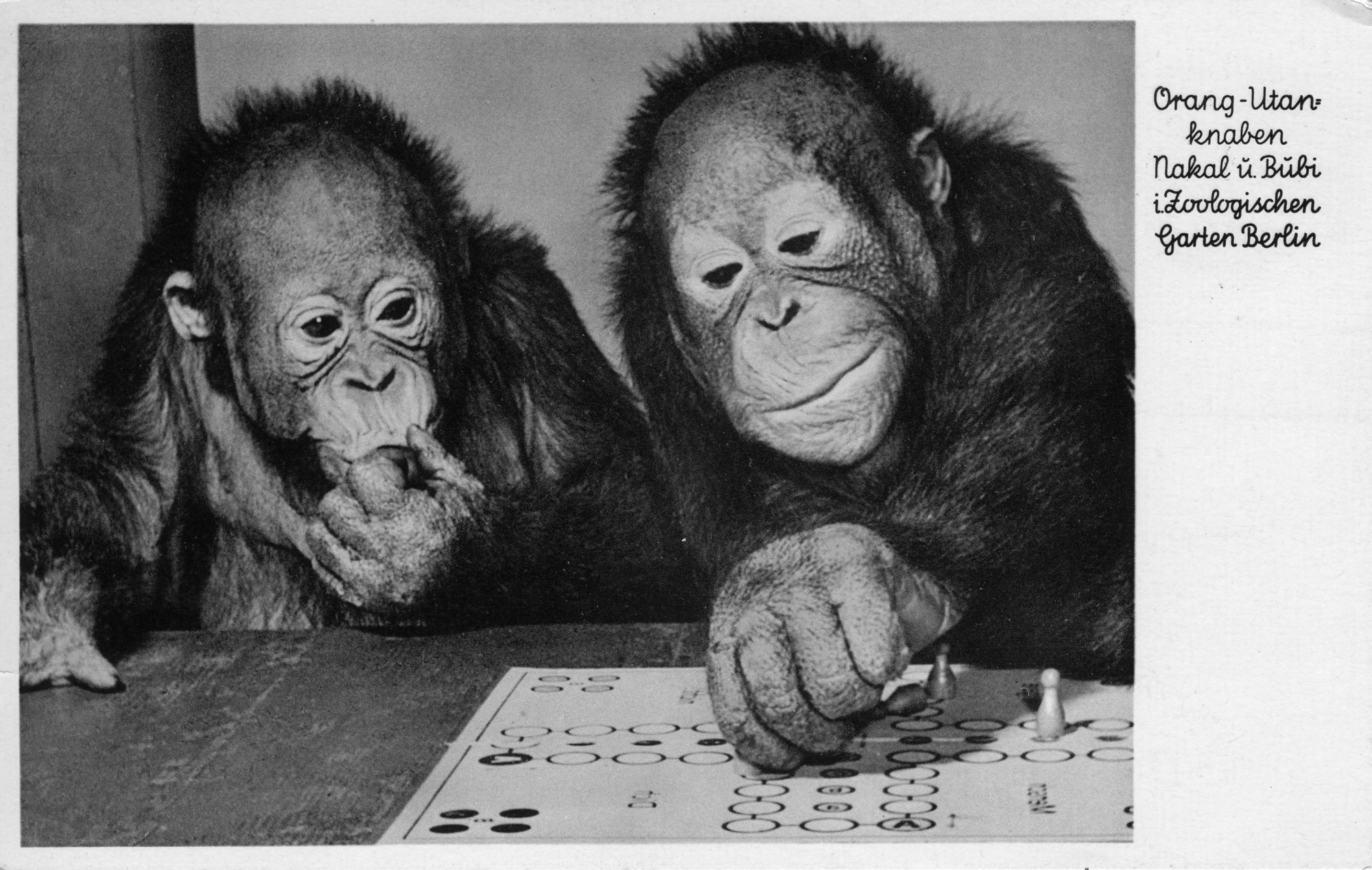

Postcard of the Zoological Garden with the two orangutan cubs “Nakal” and “Bubi”, 1959.

A first cub was born in West Berlin in 1963, but died shortly after birth. To establish a breeding programme, more wild-caught orangutans would have to be acquired.11

Although the efforts to protect animals and species were certainly sincere, zoo directors already in possession of a larger group of the animals lobbied for a ban. In 1972, Heinrich Dathe agreed with the director of the Djakarta Zoo, Benjamin Galstaun, that the “great conservationists” in the “West” (meaning Bernhard Grzimek and the management of the Stuttgart Wilhelma) sought to protect those animals already in their collection.12 We might also surmise that zoos, which were not interested in keeping the species anyway, did not want their competitors to obtain crowd pullers and could therefore prioritise animal protection without any trade-offs. In the end, no resolution was passed. The plenum merely commissioned Bernhard Grzimek to draft a resolution.

At the meeting of the German association in 1966, the self-commitment from 1962 to no longer acquire wild-caught orangutans was rescinded. But already the following year the species was back on the agenda. It was decided that members should henceforth no longer buy orangutans without a government export license. In addition, Bernhard Grzimek was appointed chairman in matters concerning the import of orangutans. He was given far-reaching powers. For example, in the event of misconduct, he was to be able to demand the expulsion of the member from the association.13 However, the regulation could only affect animals that were caught and exported from the countries of origin without an export license. With an appropriate license, the endangered primates could still be legally imported and acquired by German zoos, even though these licenses for orangutans were rare to obtain.

The basic conflict within the zoological community concerned the mode of conservation: Heinrich Dathe argued for ex-situ species protection (i.e. keeping and breeding outside the original natural habitat), others for in-situ conservation, that is, for the strict protection of animals in their natural habitat. The latter excluded and mostly excludes  catching animals for zoos. Dathe’s position and that of other zoo directors across the world integrated in-situ conservation while retaining an attractive stock of animals at their respective zoos for breeding and possibly re-wilding. In advocating for this approach, the zoo directors invoked various exemplary breeding programmes.

catching animals for zoos. Dathe’s position and that of other zoo directors across the world integrated in-situ conservation while retaining an attractive stock of animals at their respective zoos for breeding and possibly re-wilding. In advocating for this approach, the zoo directors invoked various exemplary breeding programmes.

Role Models for Breeding Programmes

The Père David’s deer was the object of an early breeding programme in captivity that proved successful and that might have inspired Heinrich Dathe and others. In the 1890s, the Père David’s deer was narrowly saved from  extinction. The Duke of Bedford brought a group of 18 animals from various international zoos to his private zoo in Woburn, where they successfully reproduced.14 In 1905, the American Bison Society was founded with the aim of preserving the nearly extinct bison. The population of these buffalo had been decimated to a few small groups due to intensive hunting by European settlers. The director of the New York Zoological Park and former taxidermist of the National Museum, William Hornaday, put together a breeding group of bison from various US zoos, which successfully produced offspring.15 When US President Theodore Roosevelt established the first national parks, Hornaday and his fellow campaigners began to release the animals into the wild. For the first time, an endangered species bred in zoos was released into the wild. The large bison was not only easy to breed and reproduced well in human care, it also received the necessary publicity. Its size, its dangerousness, but also its iconic role in the European narrative of the history of the US West undoubtedly contributed to this. The passenger pigeon, on the other hand, whose flocks once darkened the skies over the USA, did not receive this attention and became extinct around 1900. Some of their kind continued living in zoos beyond 1900, but no one made any significant attempt to breed them and preserve the species.16 Both bison and passenger pigeons were once similarly numerous and omnipresent in North America, but the responses to their impending extinction could not have been more different.

extinction. The Duke of Bedford brought a group of 18 animals from various international zoos to his private zoo in Woburn, where they successfully reproduced.14 In 1905, the American Bison Society was founded with the aim of preserving the nearly extinct bison. The population of these buffalo had been decimated to a few small groups due to intensive hunting by European settlers. The director of the New York Zoological Park and former taxidermist of the National Museum, William Hornaday, put together a breeding group of bison from various US zoos, which successfully produced offspring.15 When US President Theodore Roosevelt established the first national parks, Hornaday and his fellow campaigners began to release the animals into the wild. For the first time, an endangered species bred in zoos was released into the wild. The large bison was not only easy to breed and reproduced well in human care, it also received the necessary publicity. Its size, its dangerousness, but also its iconic role in the European narrative of the history of the US West undoubtedly contributed to this. The passenger pigeon, on the other hand, whose flocks once darkened the skies over the USA, did not receive this attention and became extinct around 1900. Some of their kind continued living in zoos beyond 1900, but no one made any significant attempt to breed them and preserve the species.16 Both bison and passenger pigeons were once similarly numerous and omnipresent in North America, but the responses to their impending extinction could not have been more different.

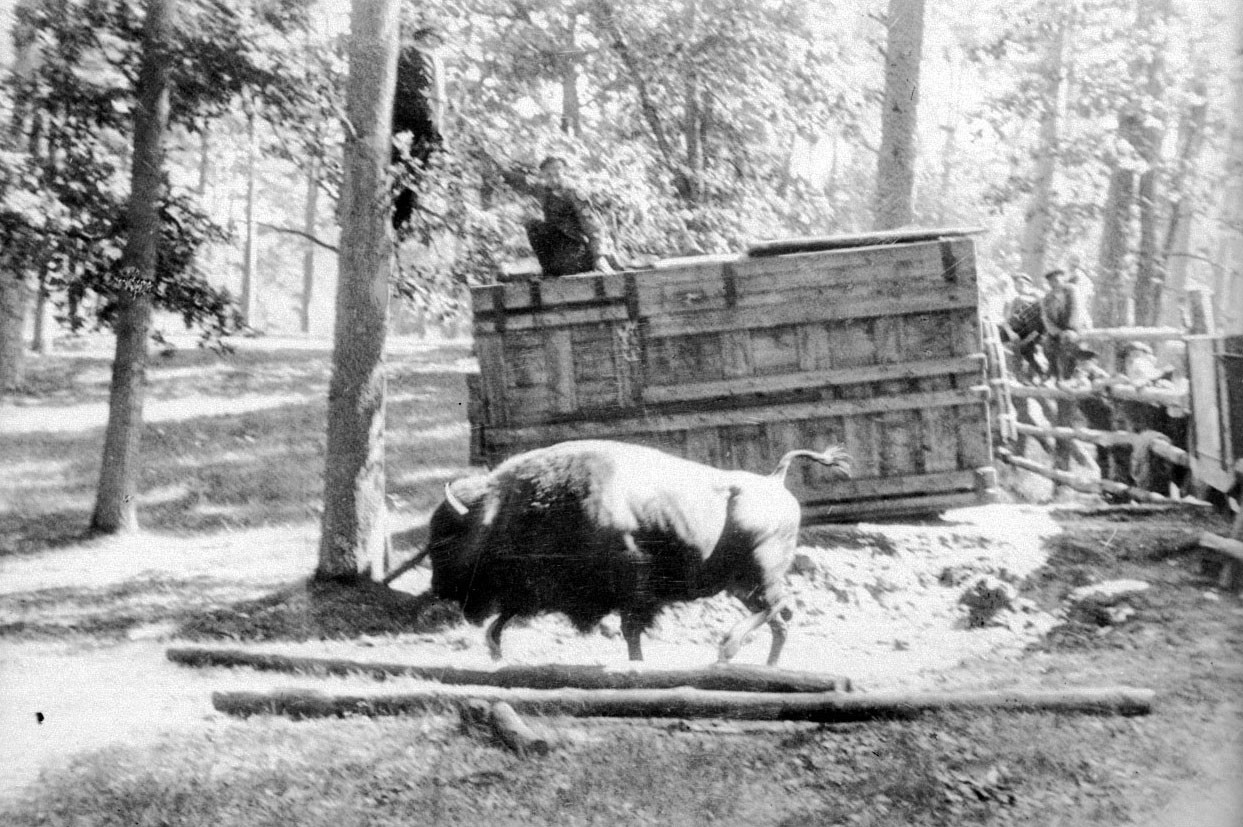

In Europe, a few years later, zoo directors turned their attention to the bison’s European counterpart – the wisent. This megaherbivore had a similar ecological function here long ago as the American bison. In 1923, European zoos founded the Society for the Protection of the European Bison, the first international breeding community. With the wisent studbook kept by its members, this species was successfully bred and saved from extinction. Through the collection and combination of the few remaining breeding groups, the stocks kept in zoos now form a population sufficient for the reintroduction efforts begun since the 1930s.17

Picture of the release of a wisent into the wild in the Schorfheide, probably 1938. (AZGB, all rights reserved.)

Further Developments: Stud Books and Captive Breeding Programmes

The success of these early captive breeding programmes encouraged the zoos to introduce more studbooks – just at the time when Dathe, Klös and Grzimek were arguing about the best strategy for orangutan conservation. At the 1966 meeting of the International Association of Zoo Directors in Colombo, more zoos committed to keeping studbooks for endangered species. The following zoos took the lead in managing studbooks:

- Antwerp for okapis and bonobos

- Basel for the armoured rhinoceros and pygmy hippopotamus

- Zoo Berlin for black and white rhinos

- Tierpark Berlin for wild asses

- Colombo for the Black-billed Stork

- Frankfurt for gorillas

- Paris for lyrebirds

- Prague undertook to take over the studbook for the Przewalski’s horse and endangered subspecies of the tiger

- San Diego took over the studbook for the Mendes antelope

- Washington took over the studbook for the orangutan18

The sources do not allow a detailed reconstruction of why these zoos opted for these specific species. We can, however, assume that they could prove a history of successful keeping and breeding (from the association’s point of view) for the animals in question.

Example of a studbook: The International Studbook for the White Rhino, 2001.

It is evident today that a mode of species conservation prevailed that favoured the establishment of a reserve population kept in zoos. Heinrich Dathe remained one of its most influential advocates. When the International Association of Zoo Directors met in Japan in 1973, he delivered a lecture entitled “Remarks to Zoological Gardens as important places for conservation and breeding of threatened species”.19 The lecture itself has not survived, but it is clear from the title that he promoted his idea of species protection through captive breeding in zoos.

This approach was and remains populat among zoos in Germany and beyond. For some years now, it has also been supported by digital data exchange via the  Species360 platform. The stud books printed over many decades have thus been replaced. Most breeding or captive breeding programmes in European zoos have been organised for several decades within the framework of the European Association of Zoos and Aquariums (EAZA) as so-called EEPs (EAZA Ex-situ Program, that is breeding programmes in captivity).

Species360 platform. The stud books printed over many decades have thus been replaced. Most breeding or captive breeding programmes in European zoos have been organised for several decades within the framework of the European Association of Zoos and Aquariums (EAZA) as so-called EEPs (EAZA Ex-situ Program, that is breeding programmes in captivity).

However, this change was not entirely voluntary: in 1973, after years of preparation and various drafts, the so-called Washington Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) entered into force. It prohibits or regulates trade in endangered species, provided they are listed in one of the regularly revised appendices to the treaty. The treaty effectively ended the international commercial  wholesale trade in zoo animals that had flourished until then. While non-protected birds and aquatic fauna could continue to be traded, this was (and is) largely no longer the case for mammals and large species, in particular. Rotterdam zoo director Dick van Dam emphasised the impact of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species in his presentation “The Future of Zoological Gardens” at the 1980 annual conference of the International Association of Zoo Directors. Van Dam called on zoos worldwide to make the breeding of endangered species one of their central tasks because the financial and legal difficulties in acquiring wild-caught animals had become too great. Only through breeding could zoos henceforth ensure the attractiveness of their own collections.20 In 1993, the Cologne zoo director Gunther Nogge confirmed that, after CITES, zoos focused much more on breeding since they had to become “self-supporting”.21

wholesale trade in zoo animals that had flourished until then. While non-protected birds and aquatic fauna could continue to be traded, this was (and is) largely no longer the case for mammals and large species, in particular. Rotterdam zoo director Dick van Dam emphasised the impact of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species in his presentation “The Future of Zoological Gardens” at the 1980 annual conference of the International Association of Zoo Directors. Van Dam called on zoos worldwide to make the breeding of endangered species one of their central tasks because the financial and legal difficulties in acquiring wild-caught animals had become too great. Only through breeding could zoos henceforth ensure the attractiveness of their own collections.20 In 1993, the Cologne zoo director Gunther Nogge confirmed that, after CITES, zoos focused much more on breeding since they had to become “self-supporting”.21

Ex-situ Breeding vs. In-Situ Species Conservation Programmes

Since the adoption of CITES, the dilemma in which Heinrich Dathe, Heinz-Georg Klös or Bernhard Grzimek still found themselves in the 1960s has been resolved: zoos can now no longer choose whether to buy individuals of sought-after species such as orangutans from the wild and thus contribute to the destruction of the species, or to refrain from showing the species. They are simply prohibited from purchasing wild-caught endangered species. At the same time, advances in wildlife biology have meant that many of the sought-after and endangered species can be kept and successfully bred in zoos with a longer lifespan. The crucial question zoos face today concerns the precise shape of their participation in global efforts to protect endangered species. Should they develop a genetically diverse ‘reserve population’ in their breeding programmes in order to be able to release them back into their original habitats? This would only be possible if man-made habitat loss is halted, or reversed through renaturation programmes. Or should they also actively advocate and promote species conservation programmes locally on-site?22

Virtually all zoos organised in the German, European and international zoo associations are committed to one form of species conservation, depending on their financial possibilities. In fact, the associations’ mission statements explicitly call on their members to do so. The Berlin Zoological Garden and the Berlin Zoo, for example, are involved in the breeding and reintroduction of bearded vultures, wisent and the Vietnam pheasant.23 The wisent project is supported by the Azerbaijani Ministry of Environment, WWF, EAZA and other local national partners. Here, animals from European zoos involved in the programme were acclimatised and cared for at Tierpark Berlin before, in 2019, being transported to the reintroduction centre in Shahdag National Park. Other examples of reintroduction programmes by member zoos of the German Association of Zoological Gardens include, in addition to the wisent, the European pond turtle, the Przewalski’s horse, the Ural owl, the Lear’s macaw, the Alpine ibex and the European hamster.24 Zoos also fund research projects and conservation reserves in some species’ regions of origin. But this involvement by European zoos can be problematic since it harbours the danger of perpetuating colonial patterns of thought and colonial dependencies.

Colonial Heritage and Patronising Aid

The origins of the conservation movement and of national parks in particular lie in colonial hunting traditions and relations of domination.25 For example, the historian Bernhard Gißibl has explained in numerous contributions how ‘nature’ became a resource of  German colonialism that was to be both exploited and protected.26 Environmental historian Frank Uekötter traces this politicisation and economisation of nature using the example of the nature conservation movement of the

German colonialism that was to be both exploited and protected.26 Environmental historian Frank Uekötter traces this politicisation and economisation of nature using the example of the nature conservation movement of the  1930s. He has investigated the roots of the German conservation movement in nationalist resentment, its impact on National Socialist ideology, and its consequences to the present day.27 The best-known representative of modern habitat conservation, Bernhard Grzimek, was implicated in these paradigms. We can see many examples in his work, such as when he advocated for the forcible expropriation of people to make space for nature reserves in the Serengeti.28 Colonial patterns prevail in modern species, too.29 Zoos worldwide – and especially those managed by former colonial powers – must therefore face the conflict-ridden legacy of modern concepts of species conservation. They will otherwise reproduce colonial structures through their conservation and research programmes.

1930s. He has investigated the roots of the German conservation movement in nationalist resentment, its impact on National Socialist ideology, and its consequences to the present day.27 The best-known representative of modern habitat conservation, Bernhard Grzimek, was implicated in these paradigms. We can see many examples in his work, such as when he advocated for the forcible expropriation of people to make space for nature reserves in the Serengeti.28 Colonial patterns prevail in modern species, too.29 Zoos worldwide – and especially those managed by former colonial powers – must therefore face the conflict-ridden legacy of modern concepts of species conservation. They will otherwise reproduce colonial structures through their conservation and research programmes.

The World Zoo Association notes in its 2015 World Conservation Strategy:

“If the zoological community can align some of its conservation objectives with human-development goals, its work will resonate more strongly with political and philanthropic ambitions and the perceived relevance of support required for species conservation, and the protection of biodiversity and ecosystem services. However, this is a delicate balance between aligning the work of zoos and aquariums with human-development goals, and occasions where biodiversity responsibilities have to be supported.”30

However, the association has no control functions, and so it is up to the member zoos themselves to ensure equal participation of all stakeholders in the selection of conservation programmes and to respect the needs and strategies of local governmental and non-governmental organisations. Another difficult issue remains the selection of the species exhibited and bred.

What is Worth Protecting?

Since the 1930s, studbooks have been a proven form of species conservation in the context of zoos. However, virtually all species covered by studbooks were either mammals or those suitable for publicity as  exhibits. They were chosen because of their size and appearance, or because their endangered status was easily communicated. But what happens to endangered species that live in obscurity, are inconspicuous, are difficult to exhibit in zoos, yet are of great importance to their habitats?

exhibits. They were chosen because of their size and appearance, or because their endangered status was easily communicated. But what happens to endangered species that live in obscurity, are inconspicuous, are difficult to exhibit in zoos, yet are of great importance to their habitats?

As early as 1968, William Conway, director of the Bronx Zoo in New York, proposed an alternative solution for breeding other, less charismatic species in zoos and for conveying their importance to the public.31 Using the bullfrog as an example, he showed how questions of biology, ethology and ecology could also be presented in an exciting way using this inconspicuous animal in order to impart natural history knowledge to visitors and thus promote species conservation. However, his text received little attention from zoos, even the Bronx Zoo continued to focus on ‘popular’ species.

Having great show value, orangutans make an easy case for captive breeding. Zoos around the world highlight their efforts in communicating issues like species and habitat conservation to a broad public by exhibiting such ‘show animals’. According to zoos, the information they provide helps visitors develop an interest in habitats and their conservation. In addition, zoos argue that the display of these animals can generate the income needed to show less prominent yet endangered species.

In this way, zoos can make a contribution to species conservation without too much economic effort. For zoos, so-called ‘flagship species’ are ideal. These describe endangered species with a high show value. From the zoos’ point of view, captive breeding programmes and potential support for in-situ conservation can achieve several goals. While preserving the visitors’ zoo experience, they can also support the protection of other animal species that might share a habitat with flagship species. In any case, zoos can claim to function as centres of species conservation.32 Critics of zoos, however, question whether zoos’ educational programmes on endangered species actually have any lasting effect on visitors.33

The orangutan undoubtedly belongs to the category of flagship species. This is also the view of the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums, which used it to decorate its website on species conservation strategies in 2021.

Image on the website of the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums. https://www.waza.org/priorities/conservation/conservation-strategies (15.01.2022).

The association regards the animal as a suitable ambassador for the protection of its habitat and all species living there – just as the polar bear  “Knut” was once considered an ambassador for the protection of its Arctic habitat.

“Knut” was once considered an ambassador for the protection of its Arctic habitat.

- Heini Hediger wrote in 1965: “Show animals refer to those animals that draw large and persistent crowds in front of their enclosure or cage.“ (Heini Hediger. Mensch und Tier im Zoo: Tiergarten-Biologie. Rüschlikon-Zürich: Albert Müller, 1965: 124.) He included primates in this category. Based on his observation of visitors, Jürg Meier confirmed this in 2005. (Jürg Meier, Handbuch Zoo: Moderne Tiergartenbiologie, Bern: Haupt Verlag, 2009: 11, 115-120.)↩

- Heinz-Georg Klös. “Berliner Aquariengeschichte”. In Tierwelt hinter Glas: Das Zoo-Aquarium Berlin, Heinz-Georg Klös and Jürgen Lange (Hg.). Berlin: Arani/Haude and Spener, 1988: 9-32, 14.↩

- “Alo: Überraschung im Zoo.” Berliner Nachtausgabe, 24.01.1928.↩

- The

journale of the Zoological Garden Berlin for the years 1928, 1930 and 1933 as well as the index card for Pongo Pygmaeus from the

journale of the Zoological Garden Berlin for the years 1928, 1930 and 1933 as well as the index card for Pongo Pygmaeus from the  Steinmetz Index.↩

Steinmetz Index.↩ - In 1956 the supervisory board of the Zoological Garden forced Katharina Heinroth to resign. Ever since then, there have only been male zoo directors. Although Katharina Heinroth and Erna Mohr, the curator for mammals at the Hamburg Zoological Museum, still occasionally took part in meetings as members, a perusal of the minutes reveals that both women made hardly any, if any, contributions to the discussions at the business meetings.↩

- Minutes of the 1962 meeting of the Association of German Zoo Directors (VDZ), Archive Tiergarten Schönbrunn (ATGS), Papers of W. Fiedler, File Verband Deutscher Zoodirektoren, no. 2.↩

- Minutes of the 1965 VDZ meeting, ATGS, papers of W. Fiedler, file VDZ and WAZA, no. 1.↩

- Minutes of the 1965 meeting of the International Union of Directors of Zoological Gardens (IUDZG), AZGB, V 5/11.↩

- Minutes of the 1965 IUDZG meeting, AZGB, V 5/11.↩

- Press release by the Tierpark Berlin, 22.07.1964, Landesarchiv Berlin, C Rep. 121, no. 23.↩

- Aktien-Verein des Zoologischen Gartens Berlin. Geschäftsbericht 1962. Berlin: 1963.↩

- Carbon copy of report by H. Dathe to the MfK on his travels to Indonesia in the autumn of 1972, 21.03.1973, AZGB, O 0/1/206. Subsequent quotes are taken from there.↩

- Minutes of VDZ meetins in 1966 and 1967, ATGS, papers of W. Fiedler, file VDZ und WAZA, no. 1.↩

- Vernon N. Jr. Kisling. “Historic and Cultural Foundations of Zoo Conservation: A Narrative Timeline”. In The Ark and Beyond: The Evolution of Zoo and Aquarium Conservation, Ben A. Minteer, Jane Maienschein, James P. Collins, and George B. Rabb (eds.), Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018: 41.↩

- Hornaday espoused viciously racist views and practices. In 1906 he forced Ota Benga, a Congolese man, into an enclosure at Bronx Zoo and abused him as a ‘living specimen’. Only in 2020 did the Wildlife Conservation Society, which manages the Bronx Zoo and enabled Hornaday to establish the zoo in the first place, issue an apology for his actions. Ota Benga committed suicide in 1916. For details on racism and nature conservation, see Marouf Arif Hasian Jr. and S. Marek Muller. “Decolonizing Conservationist Hero Narratives: A Critical Genealogy of William T. Hornaday and Colonial Conservation Rhetorics”. Atlantic Journal of Communication 27 (2019): 284-296.↩

- Vgl. Mark V. Jr. Barrow. “Teetering on the Brink of Extinction: The Passenger Pigeon, the Bison, and American Zoo Culture in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries”. In The Ark and Beyond: The Evolution of Zoo and Aquarium Conservation. Ben A. Minteer, Jane Maienschein, James P. Collins, and George B. Rabb (eds.), Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2018: 51-64.↩

- More on the history of wisent breeding and the controversies concerning genetic diversity see: Erna Mohr. Der Wisent. Leipzig: Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft Geest & Portig, 1952; Ulrich Dunkel. Für die Wildnis geboren: Neue Heimat der Tiere in zoologischen Gärten. Berlin: Safari, 1967; Bernhardt Rengert. “Die Verdrängungszucht: Ein verdrängtes und verkanntes Kapitel NS-Geschichte in der Schorfheide.” Mitteilungen des Uckermärkischen Geschichtsvereins zu Prenzlau 25 (2018): 43-71; Markus Krzoska. “‘We Know Them All’: Does It Make Sense to Create a Collective Biography of the European Bison?” In Animal Biography: Re-Framing Animal Lives, André Krebber and Mieke Roscher (eds.). New York: Springer Science + Business Media, 2018: 103-117. A starkly biased narration is provided by Lutz Heck. “Der Wisent-Schutzpark in Springe und der Zoo-Berlin.” Bongo 4 (1980): 37–42.↩

- Z. Veselovsky to IUDZG member, no date, ATGS, papers of W. Fiedler, file VDZ and WAZA, no. 1.↩

- Carbon copy of Heinrich Dathe’s registration for the meeting in Japan, AZGB, V 5/35.↩

- Laura Penn, Markus Gusset and Gerald Dick. 77 Years: The History and Evolution of the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums, 1935-2012. World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (Hg.). Gland: World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA), 2012: 168. Also Dick van Dam. “The Future of Zoological Gardens”. In IUDZG: Minutes and Proceedings of the 35th Annual Conference Held from October 13-18 1980, (AZGB, V 5/64).↩

- Gunther Nogge. “Arche Zoo: Vom Tierfang zum Erhaltungszuchtprogramm”. In Berichte aus der Arche. Dieter Poley (ed.). Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag, 1993: 79-118, 80.↩

- For an introduction see: Manfred Niekisch and Volker Sommer. “Zur Relevanz des Brückenbauens”. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte 71, Nr. 9 (2021): 31-34.↩

- Information about breeding programmes at the Zoological Garden Berlin: https://www.zoo-berlin.de/de/artenschutz/weltweit/bartgeier; https://www.zoo-berlin.de/de/artenschutz/weltweit/wisent and https://www.zoo-berlin.de/de/artenschutz/weltweit/vietnamesischer-fasan (03.01.2022).↩

- VdZ. Artenschutzzentrum Zoo, 2021. https://www.vdz-zoos.org/fileadmin/PMs/2021/VdZ/VdZ-Broschuere_Artenschutzzentrum_Zoo.pdf (03.01.2022).↩

- John M. MacKenzie. The Empire of Nature: Hunting, Conservation, and British Imperialism. Manchester, New York: St. Martin‘s Press, 1997; Angela Thompsell. Hunting Africa: British Sport, African Knowledge and the Nature of Empire. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.↩

- Bernhard Gißibl. “A Bavarian Serengeti: Space, Race and Time in Nature Conservation in East Africa and Germany”. In Civilizing Nature: National Parks in Global Historical Perspective, Bernhard Gißibl, Sabine Höhler and Patrick Kupper (eds.). New York, Oxford: Berghahn, 2012: 102-119; id. “Das kolonisierte Tier: Zur Ökologie der Kontaktzonen des deutschen Kolonialismus”. In WerkstattGeschichte, Nr. 56 (2010): 7-28; id. “Jagd und Herrschaft: Zur politischen Ökologie des deutschen Kolonialismus in Ostafrika”. In Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft 56, Nr. 6 (2008): 501–20; or id. The Nature of German Imperialism: Conservation and the Politics of Wildlife in Colonial East Africa. New York: Berghahn Books, 2016.↩

- Frank Uekötter. The Green and the Brown: A History of Conservation in Nazi Germany, Cambridge, New York, Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2006.↩

- Thomas M. Lekan. Our Gigantic Zoo: A German Quest to Save the Serengeti, New York: Oxford University Press, 2020.↩

- Lara Domínguez and Colin Luoma. “Decolonising Conservation Policy: How Colonial Land and Conservation Ideologies Persist and Perpetuate Indigenous Injustices at the Expense of the Environment”, Land 9, no. 3 (2020): https://doi.org/10.3390/land9030065.↩

- Rick Barongi, Fiona A. Fisken, Martha Parker, and Markus Gusset (eds.). Committing to Conservation: The World Zoo and Aquarium Conservation Strategy. Gland: WAZA Executive Office 2015. https://www.waza.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/WAZA-Conservation-Strategy-2015_German.pdf (03.01.2022).↩

- William G. Conway. “How to Exhibit a Bullfrog: A Bed‐Time Story for Zoo Men” Curator: The Museum Journal 11, no. 4 (1968): 310-18, 318.↩

- Stephan Hübner. “‘Die afrikanischen Elefanten sind unser Flaggschiff’: Thomas Kauffels erzählt von der Geschichte des Opel-Zoos”. Hessischer Rundfunk (03.01.2022). https://www.hr2.de/podcasts/doppelkopf/die-afrikanischen-elefanten-sind-unser-flaggschiff--thomas-kauffels-erzaehlt-von-der-geschichte-des-opel-zoos,podcast-episode-82032.html (03.01.2022); for a definition of flagship species, see Jürg Meier, Handbuch Zoo: Moderne Tiergartenbiologie. Bern: Haupt Verlag, 2009): 121.↩

- See for example Volker Sommer. “Ein Etikettenschwindel”. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte 71, no. 9 (2021): 35-38; Bob Mullan and Garry Marvin, Zoo Culture, Urbana, Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1999; Hilal Sezgin. Artgerecht ist nur die Freiheit: Eine Ethik für Tiere oder Warum wir umdenken müssen. München: Verlag C.H. Beck, 2014.↩